18 ਅਗ 2025·8 ਮਿੰਟ

Soft deletes vs hard deletes: ਅਸਲ ਐਪ ਵਿਚ ਮਹੱਤਵਪੂਰਨ ਟਰੇਡਆਫ

Soft deletes ਅਤੇ hard deletes: analytics, support, GDPR-ਸਟਾਈਲ ਮਿਟਾਉ, ਅਤੇ query ਦੀ ਜਟਿਲਤਾ ਲਈ ਅਸਲ ਟਰੇਡਆਫ ਨੂੰ ਸਮਝੋ, ਨਾਲ ਹੀ ਸੁਰੱਖਿਅਤ ਰੀਸਟੋਰ ਪੈਟਰਨ।

What soft deletes and hard deletes really mean

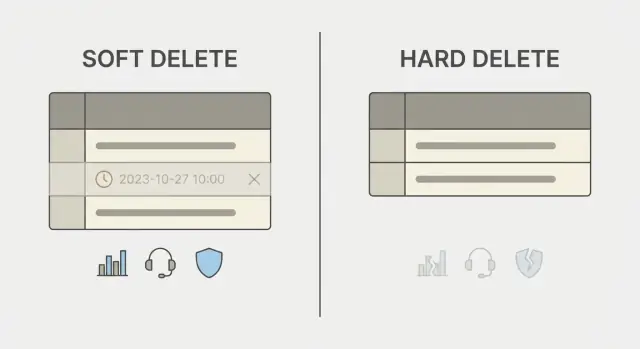

A delete button can mean two very different things in a database.

A hard delete removes the row. After that, the record is gone unless you have backups, logs, or replicas that still hold it. It’s simple to reason about, but it’s final.

A soft delete keeps the row but marks it as deleted, usually with a field like deleted_at or is_deleted. The app then treats marked rows as invisible. You keep related data, preserve history, and sometimes restore the record.

This choice shows up in day-to-day work more than people expect. It affects how you answer questions like: “Why did revenue drop last month?”, “Can you bring back my deleted project?”, or “We got a GDPR deletion request - are we actually deleting personal data?” It also shapes what “deleted” means in the UI. Users often assume they can undo it, until they can’t.

A practical rule of thumb:

- Use soft delete when users expect an undo, when support needs to recover mistakes, or when you need an audit trail.

- Use hard delete when keeping the data creates legal risk, security risk, or clear storage costs without real value.

- Use both when you want a “trash” period: soft delete first, then permanently purge later.

Example: a customer deletes a workspace and then realizes it contained invoices needed for accounting. With a soft delete, support can restore it (if your app is built to handle restores safely). With a hard delete, you’re likely stuck explaining backups, delays, or “it’s not possible.”

Neither approach is “best.” The least painful option depends on what you need to protect: user trust, reporting accuracy, or privacy compliance.

Analytics tradeoffs: accuracy vs keeping history

Deletion choices show up fast in analytics. The day you start tracking active users, conversion, or revenue, “deleted” stops being a simple state and becomes a reporting decision.

If you hard delete, many metrics look clean because removed records vanish from queries. But you also lose context: past subscriptions, past team size, or what a funnel looked like last month. A deleted customer can make historical charts shift when you re-run reports, which is scary for finance and growth reviews.

If you soft delete, you keep history, but you can accidentally inflate numbers. A simple “COUNT users” might include people who left. A churn chart can double count if you treat deleted_at as churn in one report and ignore it in another. Even revenue can get messy if invoices stay but the account is marked deleted.

What tends to work is picking a consistent reporting pattern and sticking to it:

- Filter deleted records in “current state” metrics (active users, current MRR).

- Use snapshot tables for time-based dashboards so history doesn’t change when entities get deleted later.

- Separate facts from entities: keep immutable event rows (payments, logins) even if you hide the user record.

- Treat “deleted” as a lifecycle state with its own date, and report it explicitly (created, activated, deleted).

- Define retention windows: when soft-deleted data becomes truly removed.

The key is documentation so analysts don’t guess. Write down what “active” means, whether soft-deleted users are included, and how revenue is attributed if an account is later deleted.

Concrete example: a workspace is deleted by mistake, then restored. If your dashboard counts workspaces without filtering, you’ll show a sudden drop and rebound that never happened in real usage. With snapshots, the historical chart stays stable while product views can still hide deleted workspaces.

Support and audit trail: what you can recover later

Most support tickets around deletion sound the same: “I deleted it by mistake,” or “Where did my record go?” Your delete strategy decides whether support can answer in minutes, or whether the only honest answer is “It’s gone.”

With soft deletes, you can usually verify what happened and undo it. With hard deletes, support often has to rely on backups (if you have them), and that can be slow, incomplete, or impossible for a single item. This is why the choice isn’t just a database detail. It shapes how “helpful” your product can be after something goes wrong.

A simple audit trail (what to store)

If you expect real support, add a few fields that explain deletion events:

deleted_at(timestamp)deleted_by(user id or system)delete_reason(optional, short text)deleted_from_ipordeleted_from_device(optional)restored_atandrestored_by(if you support restore)

Even without a full activity log, these details let support answer: who deleted it, when it happened, and whether it was an accident or an automated cleanup.

What hard deletes mean for support

Hard deletes can be fine for temporary data, but for user-facing records they change what support can do.

Support can’t restore a single record unless you built a recycle bin elsewhere. They may need a full backup restore, which can affect other data. They also can’t easily prove what happened, which leads to long back-and-forth.

Restore features change workload too. If users can self-restore within a time window, tickets drop. If restore requires support to act manually, tickets might increase, but they become quick and repeatable instead of one-off investigations.

GDPR-style deletion: soft delete is not full deletion

“Right to be forgotten” usually means you must stop processing a person’s data and remove it from places where it’s still usable. It doesn’t always mean you must wipe every historical aggregate immediately, but it does mean you shouldn’t keep identifiable data “just in case” if you no longer have a legal reason to keep it.

This is where soft delete vs hard delete becomes more than a product choice. A soft delete (like setting deleted_at) often only hides the record from the app. The data is still in the database, still queryable by admins, and often still present in exports, search indexes, and analytics tables. For many GDPR deletion requests, that is not erasure.

You still need a purge when:

- A user asks for deletion and you have no valid retention reason (like invoicing rules).

- You stored special category data and your policy says it must be removed.

- The record appears in user-facing exports or can be recovered by support.

- A third-party processor (email, analytics, support tools) still holds it.

Backups and logs are the part teams forget. You may not be able to delete a single row from an encrypted backup, but you can set a rule: backups expire quickly, and restored backups must re-apply deletion events before the system goes live. Logs should avoid storing raw personal data where possible, and have clear retention limits.

A simple, practical policy is a two-step delete:

- Soft delete immediately (so the product behaves correctly, accounts are disabled, and “restore deleted records” can work for mistakes).

- Start a retention timer (for example, 7 to 30 days) and schedule a purge job that hard-deletes or anonymizes personal fields.

- Record what happened in an audit trail using non-identifying markers (timestamps, reason codes) so support can explain actions without keeping the data.

If your platform supports source code export or data export, treat exported files as data stores too: define where they live, who can access them, and when they’re deleted.

Query complexity and product behavior: the hidden cost

Export source when ready

Generate the app, then export the codebase to keep full control.

Soft deletes sound simple: add a deleted_at (or is_deleted) flag and hide the row. The hidden cost is that every place you read data now needs to remember that flag. Miss it once, and you get weird bugs: totals include deleted items, search shows “ghost” results, or a user sees something they thought was gone.

UI and UX edge cases show up fast. Imagine a team deletes a project named “Roadmap” and later tries to create a new “Roadmap”. If your database has a unique rule on name, the create can fail because the deleted row still exists. Search can also confuse people: if you hide deleted items in lists but not in global search, users will think your app is broken.

Soft delete filters are commonly missed in:

- Admin dashboards and support tools

- Background jobs (emails, reminders, cleanups)

- Analytics queries and exports

- Permission checks (“does this record exist?”)

- Autocomplete and search

Performance is usually fine at first, but the extra condition adds work. If most rows are active, filtering deleted_at IS NULL is cheap. If many rows are deleted, the database has to skip more rows unless you add the right index. In plain terms: it’s like looking for current documents in a drawer that also contains lots of old ones.

A separate “Archive” area can reduce confusion. Make the default view show only active records, and put deleted items in one place with clear labels and a time window. In tools built quickly (for example, internal apps made on Koder.ai), this product decision often prevents more support tickets than any clever query trick.

Common data models for soft delete

Soft delete isn’t one feature. It’s a data model choice, and the model you pick will shape everything that follows: query rules, restore behavior, and what “deleted” means to your product.

Model 1: deleted_at plus deleted_by

The most common pattern is a nullable timestamp. When a record is deleted, set deleted_at (and often deleted_by to the user id). “Active” records are those where deleted_at is null.

This works well when you need a clean restore: restoring is just clearing deleted_at and deleted_by. It also gives support a simple audit signal.

Model 2: explicit status states

Instead of a timestamp, some teams use a status field with clear states like active, archived, and deleted. This is helpful when “archived” is a real product state (hidden from most screens but still counted in billing, for example).

The cost is rules. You must define what each state means everywhere: search, notifications, exports, and analytics.

Model 3: split storage for high-value records

For sensitive or high-value objects, you can move deleted rows into a separate table, or record an event in an append-only log.

- Timestamp soft delete:

deleted_at,deleted_by - State machine:

statuswith named states - Separate deleted table: the “active” table stays small

- Event log: keep “who did what” without keeping full rows forever

This is often used when restores must be tightly controlled, or when you want an audit trail without mixing deleted data into everyday queries.

Child records need an intentional rule too. If a workspace is deleted, what happens to projects, files, and memberships?

- Cascade: mark children deleted as well

- Restrict: block delete until children are handled

- Archive: convert children to

archived(not deleted) - Detach: remove relationships but keep the child

Pick one rule per relationship, write it down, and keep it consistent. Most “restore went wrong” bugs come from parent and child records using different meanings of deleted.

How to implement a safe restore feature (step by step)

A restore button sounds simple, but it can quietly break permissions, resurrect old data into the wrong place, or confuse users if “restored” doesn’t mean what they expect. Start by writing down the exact promise your product makes.

A practical restore flow

Use a small, strict sequence so restore is predictable and auditable.

- Define what “restore” means. Will the record keep the same ID? Should it return to the same parent (workspace, project) and keep the same relationships? Decide what happens to memberships, roles, and visibility.

- Make the user confirm and capture a reason. Show what will be restored (name, owner, last modified date) and require a clear confirmation. For support teams, a short reason field (“deleted by mistake”, “closing ticket”) is often enough.

- Check for conflicts before changing anything. Common issues: the old name was reused, the user no longer has permission, or related records were hard-deleted. Choose a rule: block restore with a clear message, or restore into a safe “needs review” state.

- Log the restore action. Record who restored, when, from where (UI, API), and what changed. This helps audits and support, and it’s essential when someone asks, “Why did this come back?”

- Add a time limit when it fits. Many apps allow restores for 30 or 90 days, then require a different recovery process or treat it as permanent.

If you build apps quickly in a chat-driven tool like Koder.ai, keep these checks as part of the generated workflow so every screen and endpoint follows the same rules.

Common mistakes and traps to avoid

Build a safe restore flow

Create a recycle bin and conflict checks with a chat-driven workflow.

The biggest pain with soft deletes isn’t the delete itself, but all the places that forget the record is “gone.” Many teams choose soft delete for safety, then accidentally show deleted items in search results, badges, or totals. Users notice fast when a dashboard says “12 projects” but only 11 appear in the list.

A close second is access control. If a user, team, or workspace is soft-deleted, they shouldn’t be able to log in, call the API, or receive notifications. This often slips through when the login check looks up by email, finds the row, and never checks the deleted flag.

Common traps that create support tickets later:

- Missing the deleted filter in one read path (admin views, exports, search, background jobs).

- Restoring records that collide with unique fields (email, username, slug, invoice number).

- Deleting a parent but leaving children “active” (or deleting children while the parent still looks alive).

- Counting deleted rows in analytics, quotas, or billing calculations.

- Sending deleted data to third parties because integrations and sync jobs don’t understand “deleted”.

Uniqueness collisions are especially nasty during restore. If someone creates a new account with the same email while the old one is soft-deleted, a restore either fails or overwrites the wrong identity. Decide your rule ahead of time: block reuse until purge, allow reuse but disallow restore, or restore under a new identifier.

One common scenario: a support agent restores a soft-deleted workspace. The workspace comes back, but its members stay deleted, and an integration resumes syncing old records into a partner tool. From the user’s view, the restore “half worked” and caused a new mess.

Before you ship restore, make these behaviors explicit:

- What “deleted” means for login, API access, and notifications

- How restore handles unique fields and ownership

- How related records follow the parent (all-or-nothing beats surprises)

- How exports and integrations treat deleted data (exclude, mark, or send tombstones)

Realistic example: a workspace deleted by mistake

A B2B SaaS team has a “Delete workspace” button. One Friday, an admin runs a cleanup and removes 40 workspaces that looked inactive. On Monday, three customers complain that their projects are gone and ask for an immediate restore.

The team assumed the decision would be simple. It wasn’t.

First problem: support can’t restore what was truly deleted. If the workspace row is hard-deleted and cascades removed projects, files, and memberships, the only option is backups. That means time, risk, and an awkward answer to the customer.

Second problem: analytics looks broken. The dashboard counts “active workspaces” by querying only rows where deleted_at IS NULL. The accidental deletion makes charts show a sudden drop in adoption. Worse, a weekly report compares to last week and flags a false churn spike. The data wasn’t lost, but it was excluded in the wrong places.

Third problem: a privacy request arrives for one of the affected users. They ask to delete their personal data. A pure soft delete doesn’t satisfy this. The team needs a plan to purge personal fields (name, email, IP logs) while keeping non-personal aggregates like billing totals and invoice numbers.

Fourth problem: everyone asks, “Who clicked delete?” If there’s no trail, support can’t explain what happened.

A safer pattern is to treat deletion as an event with clear metadata:

- Mark the workspace deleted (and hide it in the product)

- Record

deleted_by,deleted_at, and a reason or ticket id - Log what will be affected (project count, seats, storage)

- Allow restore within a time window, then purge selected personal fields when required

This is the kind of workflow teams often build quickly in platforms like Koder.ai, then later realize the delete policy needs just as much design as the features around it.

Quick checklist to pick the right delete strategy

Implement GDPR style purges

Set retention timers and purge jobs so hidden data does not linger.

Picking between soft deletes vs hard deletes is less about preference and more about what your app must guarantee after a record is “gone.” Ask these questions before you write a single query.

- Do you ever need real erasure? If you must honor privacy or legal requests, plan for true deletion (and backups, exports, and caches too). A soft delete flag alone doesn’t meet “remove it completely”.

- Do you need a restore button, and for how long? If “undo” matters, decide the restore window (7 days, 30 days, forever) and what happens after it expires.

- Will reporting need the old data after deletion? Some teams want charts to reflect what users see today; others need historical counts for finance or growth analysis. Your delete choice changes what “active users” and “total revenue” mean.

- Can support explain what happened without detective work? If you expect tickets like “my project disappeared”, you need a clear trail: who deleted it, when, and from where, plus enough data to investigate.

- Can your team keep behavior consistent everywhere? Soft deletes often create hidden rules: every query must filter out deleted records, every join must behave, and every screen must agree on what “deleted” means.

A simple way to sanity-check the decision is to pick one realistic incident and walk it through. For example: someone deletes a workspace by mistake on Friday night. On Monday, support needs to see the deletion event, restore it safely, and avoid reviving related data that should stay removed. If you’re building an app on a platform like Koder.ai, define these rules early so your generated backend and UI follow one policy instead of sprinkling special cases across the code.

Next steps: choose a policy and build it safely

Pick your approach by writing a simple policy you can share with your team and support. If it’s not written down, it will drift, and users will feel the inconsistency.

Start with a plain set of rules:

- What gets soft-deleted (and how long it stays restorable)

- What gets hard-deleted immediately (and why)

- When soft-deleted data is purged (for example after X days)

- Who can restore, and what proof or approval is required

- How privacy-driven deletion requests are handled end to end

Then build two clear paths that never get mixed up: an “admin restore” path for mistakes, and a “privacy purge” path for real deletion. The restore path should be reversible and logged. The purge path should be final and remove or anonymize all related data that can identify a person, including backups or exports if your policy requires it.

Add guardrails so deleted data doesn’t leak back into the product. The easiest way is to treat “deleted” as a first-class state in your tests. Add review checkpoints for any new query, list page, search, export, and analytics job. A good rule is: if a screen shows user-facing data, it must have an explicit decision about deleted records (hide, show with a label, or admin-only).

If you’re early in a product, prototype both flows before you lock in the schema. In Koder.ai, you can sketch the deletion policy in planning mode, generate the basic CRUD, and quickly try restore and purge scenarios, then adjust the data model before committing.