Aug 31, 2025·6 min

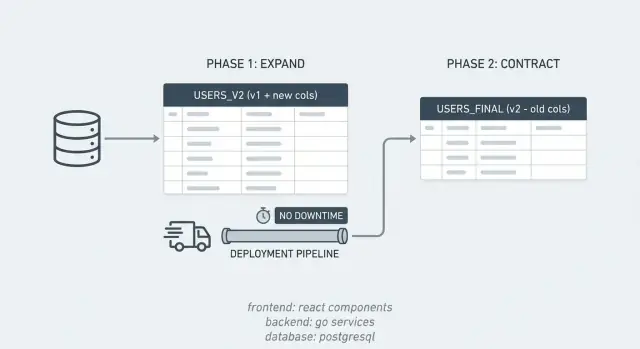

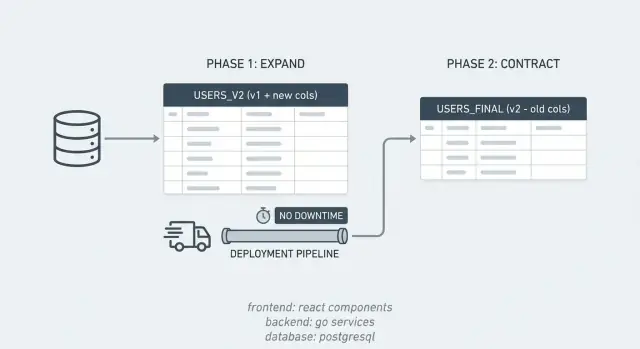

Zero-downtime schema changes with expand/contract pattern

Learn zero-downtime schema changes using the expand/contract pattern: add columns safely, backfill in batches, deploy compatible code, then remove old paths.

Learn zero-downtime schema changes using the expand/contract pattern: add columns safely, backfill in batches, deploy compatible code, then remove old paths.

Downtime from a database change isn't always a clean, obvious outage. To users it can look like a page that loads forever, a checkout that fails, or an app that suddenly shows "something went wrong." For teams it shows up as alerts, rising error rates, and a backlog of failed writes that need cleanup.

Schema changes are risky because the database is shared by every running version of your app. During a release you often have old and new code live at the same time (rolling deploys, multiple instances, background jobs). A migration that looks correct can still break one of those versions.

Common failure modes include:

Even when the code is fine, releases get blocked because the real problem is timing and compatibility across versions.

Zero-downtime schema changes come down to one rule: every intermediate state must be safe for both old and new code. You change the database without breaking existing reads and writes, ship code that can handle both shapes, and only remove the old path once nothing depends on it.

That extra effort is worth it when you have real traffic, strict SLAs, or lots of app instances and workers. For a tiny internal tool with a quiet database, a planned maintenance window may be simpler.

Most incidents from database work happen because the app expects the database to change instantly, while the database change takes time. The expand/contract pattern avoids that by breaking one risky change into smaller, safe steps.

For a short period, your system supports two "dialects" at once. You introduce the new structure first, keep the old one working, move data gradually, then clean up.

The pattern is simple:

This plays nicely with rolling deploys. If you update 10 servers one by one, you'll briefly run old and new versions together. Expand/contract keeps both compatible with the same database during that overlap.

It also makes rollbacks less scary. If a new release has a bug, you can roll back the app without rolling back the database, because the old structures still exist during the expand window.

Example: you want to split a PostgreSQL column full_name into first_name and last_name. You add the new columns (expand), ship code that can write and read both shapes, backfill old rows, then drop full_name once you're confident nothing uses it (contract).

The expand phase is about adding new options, not removing old ones.

A common first move is adding a new column. In PostgreSQL, it's usually safest to add it as nullable and without a default. Adding a non-null column with a default can trigger a table rewrite or heavier locks, depending on your Postgres version and the exact change. A safer sequence is: add nullable, deploy tolerant code, backfill, then later enforce NOT NULL.

Indexes also need care. Creating a normal index can block writes longer than you expect. When you can, use concurrent index creation so reads and writes keep flowing. It takes longer, but avoids the release-stopping lock.

Expand can also mean adding new tables. If you're moving from a single column to a many-to-many relationship, you might add a join table while keeping the old column in place. The old path keeps working while the new structure starts collecting data.

In practice, expand often includes:

After expand, old and new app versions should be able to run at the same time without surprises.

Most release pain happens in the middle: some servers run new code, others still run old code, while the database is already changing. Your goal is straightforward: any version in the rollout should work with both the old and the expanded schema.

A common approach is dual-write. If you add a new column, the new app writes to both the old and the new column. Old app versions keep writing only the old one, which is fine because it still exists. Keep the new column optional at first, and delay strict constraints until you're sure all writers have been upgraded.

Reads usually switch more carefully than writes. For a while, keep reads on the old column (the one you know is fully populated). After backfill and verification, switch reads to prefer the new column, with a fallback to the old if the new is missing.

Also keep your API output stable while the database changes underneath. Even if you introduce a new internal field, avoid changing response shapes until all consumers are ready (web, mobile, integrations).

A rollback-friendly rollout often looks like this:

The key idea is that the first irreversible step is dropping the old structure, so you postpone it until the end.

Backfilling is where many "zero-downtime schema changes" go wrong. You want to fill the new column for existing rows without long locks, slow queries, or surprise load spikes.

Batching matters. Aim for batches that finish quickly (seconds, not minutes). If each batch is small, you can pause, resume, and tune the job without blocking releases.

To track progress, use a stable cursor. In PostgreSQL that's often the primary key. Process rows in order and store the last id you completed, or work in id ranges. This avoids expensive full-table scans when the job restarts.

Here is a simple pattern:

UPDATE my_table

SET new_col = ...

WHERE new_col IS NULL

AND id > $last_id

ORDER BY id

LIMIT 1000;

Make the update conditional (for example, WHERE new_col IS NULL) so the job is idempotent. Reruns only touch rows that still need work, which reduces unnecessary writes.

Plan for new data arriving during the backfill. The usual order is:

A good backfill is boring: steady, measurable, and easy to pause if the database gets hot.

The riskiest moment isn't adding the new column. It's deciding you can rely on it.

Before you move to contract, prove two things: the new data is complete, and production has been reading it safely.

Start with completeness checks that are fast and repeatable:

If you're dual-writing, add a consistency check to catch silent bugs. For example, run a query hourly that finds rows where old_value <> new_value and alert if it's not zero. This is often the quickest way to discover that one writer still updates only the old column.

Watch basic production signals while the migration runs. If query time or lock waits spike, even your "safe" verification queries may be adding load. Monitor error rates for any code paths that read the new column, especially right after deploys.

How long should you keep both paths? Long enough to survive at least one full release cycle and one backfill rerun. Many teams use 1-2 weeks, or until they're confident no old app version is still running.

Contract is where teams get nervous because it feels like the point of no return. If expand was done right, contract is mostly cleanup, and you can still do it in small, low-risk steps.

Pick the moment carefully. Don't drop anything right after a backfill finishes. Give it at least one full release cycle so delayed jobs and edge cases have time to show themselves.

A safe contract sequence usually looks like this:

If you can, split contract into two releases: one that removes code references (with extra logging), and a later one that removes database objects. That separation makes rollback and troubleshooting much easier.

PostgreSQL specifics matter here. Dropping a column is mostly a metadata change, but it still takes an ACCESS EXCLUSIVE lock briefly. Plan for a quiet window and keep the migration fast. If you created extra indexes, prefer dropping them with DROP INDEX CONCURRENTLY to avoid blocking writes (it can't run inside a transaction block, so your migration tooling needs to support that).

Zero-downtime migrations fail when the database and the app stop agreeing on what's allowed. The pattern works only if every intermediate state is safe for both old code and new code.

These mistakes show up often:

A realistic scenario: you start writing full_name from the API, but a background job that creates users still only sets first_name and last_name. It runs at night, inserts rows with full_name = NULL, and later code assumes full_name is always present.

Treat each step like a release that may run for days:

A repeatable checklist keeps you from shipping code that only works in one database state.

Before you deploy, confirm the database already has the expanded pieces in place (new columns/tables, indexes created in a low-lock way). Then confirm the app is tolerant: it should work against the old shape, the expanded shape, and a half-backfilled state.

Keep the checklist short:

A migration is only done when reads use the new data, writes no longer maintain the old data, and you've verified the backfill with at least one simple check (counts or sampling).

Say you have a PostgreSQL table customers with a column phone that stores messy values (different formats, sometimes blank). You want to replace it with phone_e164, but you can't block releases or take the app down.

A clean expand/contract sequence looks like this:

phone_e164 as nullable, with no default, and no heavy constraints yet.phone and phone_e164, but keep reads on phone so nothing changes for users.phone_e164 first, and falls back to phone if it's still NULL.phone_e164, remove the fallback, drop phone, then add stricter constraints if you still need them.Rollback stays simple when each step is backward compatible. If the read switch causes issues, roll back the app and the database still has both columns. If backfill causes load spikes, pause the job, reduce batch size, and continue later.

If you want the team to stay aligned, document the plan in one place: the exact SQL, which release flips reads, how you measure completion (like percent non-NULL phone_e164), and who owns each step.

Expand/contract works best when it feels routine. Write a short runbook your team can reuse for every schema change, ideally one page and specific enough that a new teammate can follow it.

A practical template covers:

Decide ownership up front. "Everyone thought someone else would do contract" is how old columns and feature flags live for months.

Even if the backfill runs online, schedule it when traffic is lower. It's easier to keep batches small, watch DB load, and stop quickly if latency climbs.

If you're building and deploying with Koder.ai (koder.ai), Planning Mode can be a useful way to map the phases and checkpoints before you touch production. The same compatibility rules still apply, but having the steps written down makes it harder to skip the boring parts that prevent outages.

Because your database is shared by every running version of your app. During rolling deploys and background jobs, old and new code can run at the same time, and a migration that changes names, drops columns, or adds constraints can break whichever version wasn’t written for that exact schema state.

It means you design the migration so every intermediate database state works for both old and new code. You add new structures first, run with both paths for a while, then remove the old structures only after nothing depends on them.

Expand adds new columns, tables, or indexes without removing anything the current app needs. Contract is the cleanup phase where you remove the old columns, old reads/writes, and temporary sync logic after you’ve proven the new path is fully working.

Adding a nullable column with no default is usually the safest starting point, because it avoids heavy locks and keeps old code working. Then you deploy code that can handle the column being missing or NULL, backfill gradually, and only later tighten constraints like NOT NULL.

It’s when the new app version writes to both the old field and the new field during the transition. That keeps data consistent while you still have older app instances and jobs that only know about the old field.

Backfill in small batches that finish quickly, and make each batch idempotent so reruns only update rows that still need work. Keep an eye on query time, lock waits, and replication lag, and be ready to pause or shrink batch size if the database starts to heat up.

First, check completeness, like how many rows still have NULL in the new column. Then do a consistency check comparing old and new values for a sample (or continuously for all rows if it’s cheap), and watch production errors right after deploys to catch code paths still using the wrong schema.

NOT NULL or new constraints can block writes while the table is validated, and normal index creation can hold locks longer than you expect. Renames and drops are also risky because older code may still reference the old names during a rolling deploy.

Only after you’ve stopped writing the old field, switched reads to the new field without relying on fallbacks, and waited long enough to be confident no old app versions or workers are still running. Many teams treat this as a separate release so a rollback stays simple.

If you can tolerate a maintenance window and there’s little traffic, a simple one-shot migration may be fine. If you have real users, multiple app instances, background workers, or an SLA, expand/contract is usually worth the extra steps because it keeps rollouts and rollbacks safer; in Koder.ai Planning Mode, writing down the phases and checks ahead of time helps you avoid skipping the “boring” steps that prevent outages.