Dec 13, 2025·6 min

Staging vs production for small teams: what to copy and fake

Staging vs production for small teams: what must match (DB, auth, domains) and what to fake (payments, emails) with a practical checklist.

Staging vs production for small teams: what must match (DB, auth, domains) and what to fake (payments, emails) with a practical checklist.

Most "it worked in staging" bugs aren't mysterious. Staging often mixes real and fake: a different database, different environment variables, a different domain, and sometimes a different login setup. The UI looks the same, but the rules underneath aren't.

The point of staging is to surface production-like failures earlier, when they're cheaper and less stressful to fix. That usually means matching the parts that control behavior under real conditions: database schema changes, auth flows, HTTPS and domains, background jobs, and the environment variables that decide how code runs.

There's an unavoidable tradeoff: the more "real" staging becomes, the more it costs and the more risk it carries (accidentally charging a card, emailing real users, leaking data). Small teams need staging that's trustworthy without becoming a second production.

A useful mental model:

Production is the real system: real users, real money, real data. If it breaks, people notice quickly. Security and compliance expectations are highest because you're handling customer information.

Staging is where you test changes before release. It should feel like production from the app's point of view, but with a smaller blast radius. The goal is to catch surprises early: a migration that fails, an auth callback that points to the wrong domain, or a background job that behaves differently once it's actually running.

Small teams usually land on one of these patterns:

You can sometimes skip staging if your app is tiny, changes are rare, and rollback is instant. Don't skip it if you take payments, send important emails, run migrations often, or have multiple people merging changes.

Parity doesn't mean staging must be a smaller copy of production with the same traffic and the same spend. It means the same actions should lead to the same outcomes.

If a user signs up, resets a password, uploads a file, or triggers a background job, staging should follow the same logic production would. You don't need production-sized infrastructure to catch production-only bugs, but you do need the same assumptions.

A simple rule that keeps staging practical:

If a difference could change control flow, data shape, or security, it must match production.

If a difference mainly affects cost or risk, simulate it.

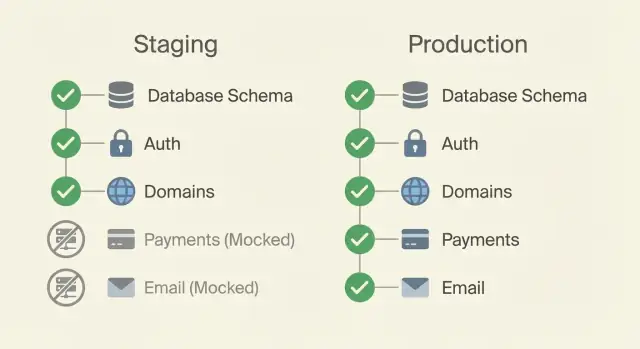

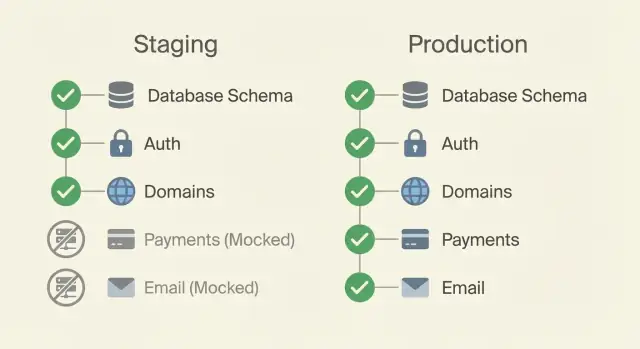

In practice, it often breaks down like this:

When you make an exception, write it down in one place. A short "staging notes" doc is enough: what's different, why it's different, and how you test the real thing safely. That small habit prevents a lot of back-and-forth later.

If staging is meant to catch surprises, the database is where most surprises hide. The rule is simple: staging schema should match production, even if staging has far less data.

Use the same migration tool and the same process. If production runs migrations automatically during deploy, staging should too. If production requires an approval step, copy that in staging. Differences here create the classic situation where code works in staging only because the schema drifted.

Keep staging data smaller, but keep the structure identical: indexes, constraints, default values, and extensions. A missing index can make staging feel fast while production slows down. A missing constraint can hide real errors until customers hit them.

Destructive changes need extra attention. Renames, drops, and backfills are where small teams get burned. Test the full sequence in staging: migrate up, run the app, and try a rollback if you support it. For backfills, test with enough rows to reveal timeouts or lock issues, even if it's not production-scale.

Plan for a safe reset. Staging databases get messy, so it should be easy to recreate from scratch and re-run all migrations end to end.

Before you trust a staging deploy, verify:

If staging doesn't use the same sign-in flow as production, it will mislead you. Keep the experience identical: the same redirects, callback paths, password rules, and second factor (SSO/OAuth/magic links/2FA) you plan to ship.

At the same time, staging must use separate credentials everywhere. Create separate OAuth apps, client IDs, and secrets for staging, even if you use the same identity provider. That protects production accounts and lets you rotate secrets safely.

Test the parts that fail most often: cookies, sessions, redirects, and callback URLs. If production uses HTTPS and a real domain, staging should too. Cookie flags like Secure and SameSite behave differently on localhost.

Also test permissions. Staging often quietly turns into "everyone is admin," and then production fails when real roles apply. Decide which roles exist and test at least one non-admin path.

One simple approach is to seed a few known accounts:

A lot of "it worked in staging" bugs come from URLs and headers, not the business logic. Make staging URLs look like production, with a clear prefix or subdomain.

If production is app.yourdomain.com, staging could be staging.app.yourdomain.com (or app-staging.yourdomain.com). This catches problems with absolute links, callback URLs, and redirects early.

HTTPS should behave the same way too. If production forces HTTPS, staging should also force it with the same redirect rules. Otherwise cookies can appear to work in staging but fail in production because Secure cookies are only sent over HTTPS.

Pay close attention to browser-facing rules:

X-Forwarded-Proto, which affect generated links and auth behaviorMany of these live in environment variables. Keep them reviewed like code, and keep the "shape" consistent between environments (same keys, different values). Common ones to double-check:

BASE_URL (or public site URL)CORS_ORIGINSBackground work is where staging breaks down quietly. The web app looks fine, but problems appear when a job retries, a queue backs up, or a file upload hits a permission rule.

Use the same job pattern you use in production: the same type of queue, the same style of worker setup, and the same retry and timeout rules. If production retries a job five times with a two-minute timeout, staging shouldn't run it once with no timeout. That's testing a different product.

Scheduled jobs need extra care. Timezone assumptions cause subtle bugs: daily reports at the wrong hour, trials ending too early, or cleanups deleting fresh files. Use the same timezone setting as production, or document the difference clearly.

Storage should be real enough to fail the way production fails. If production uses object storage, don't let staging write to a local folder. Otherwise URLs, access control, and size limits will behave differently.

A quick way to build trust is to force failures on purpose:

Idempotency matters most when money, messages, or webhooks are involved. Even in staging, design jobs so reruns don't create duplicate charges, duplicate emails, or repeated state changes.

Staging should feel like production, but it shouldn't be able to charge real cards, spam real users, or rack up surprise API bills. The goal is realistic behavior with safe outcomes.

Payments are usually first to mock. Use the provider's sandbox mode and test keys, then simulate cases that are hard to reproduce on demand: failed charges, disputed payments, delayed webhook events.

Email and notifications come next. Instead of sending real messages, redirect everything to a capture mailbox or a single safe inbox. For SMS and push, use test recipients only, or a staging-only sender that logs and drops messages while still letting you verify content.

A practical staging mock setup often includes:

Make the mocked state obvious. Otherwise people will file bugs about behavior that's expected.

Start by listing every dependency your app touches in production: database, auth provider, storage, email, payments, analytics, webhooks, background jobs.

Then create two sets of environment variables side by side: staging and production. Keep the keys identical so your code doesn't branch everywhere. Only values change: different database, different API keys, different domain.

Keep the setup repeatable:

After deploy, do a short smoke test:

Make it a habit: no production release without one clean staging pass.

Imagine a simple SaaS: users sign up, pick a plan, pay a subscription, and receive a receipt.

Copy what affects core behavior. Staging database runs the same migrations as production, so tables, indexes, and constraints match. Login follows the same redirects and callback paths, using the same identity provider rules, but with separate client IDs and secrets. Domain and HTTPS settings keep the same shape (cookie settings, redirect rules), even though the hostname is different.

Fake the risky integrations. Payments run in test mode or against a stub that can return success or failure. Emails go to a safe inbox or an internal outbox so you can verify content without sending real receipts. Webhook events can be replayed from saved samples instead of waiting on the live provider.

A simple release flow:

If staging and production must differ on purpose (for example, payments are mocked in staging), record it in a short "known differences" note.

Most staging surprises come from small differences that only show up under real identity rules, real timing, or messy data. You're not trying to mirror every detail. You're trying to make the important behavior match.

Mistakes that show up again and again:

A realistic example: you test "upgrade plan" in staging, but staging doesn't enforce email verification. The flow passes. In production, unverified users can't upgrade and support gets flooded.

Small teams win by doing the same few checks every time.

Staging often gets weaker security than production, yet it can still hold real code, real secrets, and sometimes real data. Treat it as a real system with fewer users, not a toy environment.

Start with data. The safest default is no real customer data in staging. If you must copy production data to reproduce a bug, mask anything sensitive (emails, names, addresses, payment details) and keep the copy small.

Keep access separate and minimal. Staging should have its own accounts, API keys, and credentials with the least permissions needed. If a staging key leaks, it shouldn't unlock production.

A practical baseline:

Staging only helps if the team can keep it working week after week. Aim for a steady routine, not a perfect mirror of production.

Write a lightweight standard you can actually follow: what must match, what's mocked, and what counts as "ready to deploy." Keep it short enough that people will read it.

Automate what people forget. Auto-deploy to staging on merge, run migrations during deploy, and keep a couple of smoke tests that prove the basics still work.

If you're building with Koder.ai (koder.ai), keep staging as its own environment with separate secrets and domain settings, and use snapshots and rollback as part of the normal release routine so a bad deploy is a quick fix, not a long night.

Decide who owns the checklist and who can approve a release. Clear ownership beats good intentions every time.

Aim for the same outcomes, not the same scale. If the same user action should succeed or fail for the same reason in both places, your staging is doing its job, even if it uses smaller machines and less data.

Make it trustworthy when changes can break money, data, or access. If you run migrations often, use OAuth or SSO, send important emails, process payments, or have multiple people shipping changes, staging usually saves more time than it costs.

First, database migrations and schema, because that’s where many “it worked” surprises hide. Next, auth flows and domains, because callbacks, cookies, and HTTPS rules often behave differently when the hostname changes.

Use the same migration tool and the same run conditions as production. If production runs migrations during deploy, staging should too; if production requires an approval step, staging should mirror that process so you can catch ordering, locking, and rollback issues early.

No. The safer default is keeping staging data synthetic and small, while keeping the schema identical. If you must copy production data to reproduce a bug, mask sensitive fields and limit who can access it, because staging often has weaker controls than production.

Keep the user experience identical, but use separate credentials and secrets. Create a dedicated OAuth or SSO app for staging with its own client ID, client secret, and allowed redirect URLs so a staging mistake can’t impact production accounts.

Use a staging domain that mirrors the production shape and enforce HTTPS the same way. This flushes out issues with absolute URLs, cookie flags like Secure and SameSite, redirects, and trusted proxy headers that can change behavior in real browsers.

Run the same job system style and similar retry and timeout settings so you’re testing the real product behavior. If you simplify background jobs too much in staging, you’ll miss failures caused by retries, delays, duplicate events, and worker restarts.

Use sandbox modes and test keys so you can exercise the full flow without real side effects. For email and SMS, route messages to a safe capture inbox or an internal outbox so you can verify content and triggers without sending to real customers.

Treat staging as a real system with fewer users, not a toy environment. Keep separate secrets, least-privilege access, and clear rules for logs and data retention, and make it easy to reset the environment; if you use Koder.ai, keep staging as its own environment and rely on snapshots and rollback to recover quickly from a bad deploy.