Oct 23, 2025·6 min

Server-side vs client-side filtering: a decision checklist

Server-side vs client-side filtering checklist to choose based on data size, latency, permissions, and caching, without UI leaks or lag.

Server-side vs client-side filtering checklist to choose based on data size, latency, permissions, and caching, without UI leaks or lag.

Filtering in a UI is more than a single search box. It usually includes a few related actions that all change what the user sees: text search (name, email, order ID), facets (status, owner, date range, tags), and sorting (newest, highest value, last activity).

The key question isn’t which technique is “better.” It’s where the full dataset lives, and who is allowed to access it. If the browser receives records the user should not see, a UI can expose sensitive data even if you hide it visually.

Most debates about server-side vs client-side filtering are really reactions to two failures users notice immediately:

There’s a third issue that creates endless bug reports: inconsistent results. If some filters run on the client and others run on the server, users see counts, pages, and totals that don’t match. That breaks trust quickly, especially on paginated lists.

A practical default is simple: if the user is not allowed to access the full dataset, filter on the server. If they are allowed and the dataset is small enough to load quickly, client filtering can be fine.

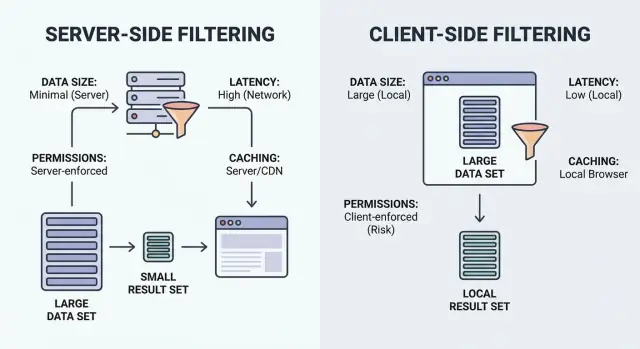

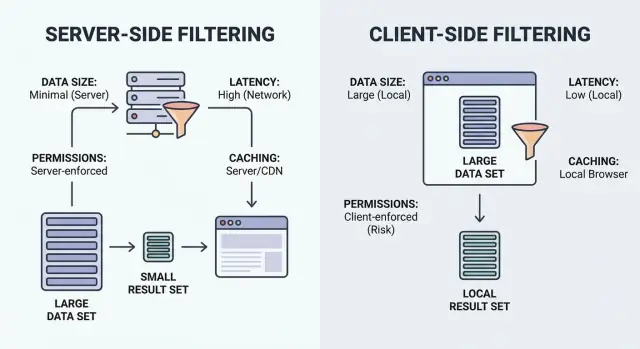

Filtering is just “show me the items that match.” The key question is where the matching happens: in the user’s browser (client) or on your backend (server).

Client-side filtering runs in the browser. The app downloads a set of records (often JSON), then applies filters locally. It can feel instant after the data is loaded, but it only works when the dataset is small enough to ship and safe enough to expose.

Server-side filtering runs on your backend. The browser sends filter inputs (like status=open, owner=me, createdAfter=Jan 1), and the server returns only matching results. In practice, this is usually an API endpoint that accepts filters, builds a database query, and returns a paginated list plus totals.

A simple mental model:

Hybrid setups are common. A good pattern is to enforce “big” filters on the server (permissions, ownership, date range, search), then use small UI-only toggles locally (hide archived items, quick tag chips, column visibility) without another request.

Sorting, pagination, and search usually belong to the same decision. They affect payload size, user feel, and what data you’re exposing.

Start with the most practical question: how much data would you send to the browser if you filter on the client? If the honest answer is “more than a few screens worth,” you’ll pay for it in download time, memory use, and slower interactions.

You don’t need perfect estimates. Just get the order of magnitude: how many rows might the user see, and what’s the average size of a row? A list of 500 items with a few short fields is very different from 50,000 items where each row includes long notes, rich text, or nested objects.

Wide records are the quiet payload killer. A table can look small by row count but still be heavy if each row contains many fields, large strings, or joined data (contact + company + last activity + full address + tags). Even if you show only three columns, teams often ship “everything, just in case,” and the payload balloons.

Also think about growth. A dataset that’s fine today can become painful after a few months. If the data grows fast, treat client-side filtering as a short-term shortcut, not a default.

Rules of thumb:

That last point matters for more than performance. “Can we ship the whole dataset to the browser?” is also a security question. If the answer isn’t a confident yes, don’t send it.

Filtering choices often fail on feel, not correctness. Users don’t measure milliseconds. They notice pauses, flicker, and results that jump around while they type.

Time can disappear in different places:

Define what “fast enough” means for this screen. A list view might need responsive typing and smooth scrolling, while a report page can tolerate a short wait as long as the first result appears quickly.

Don’t judge only on office Wi-Fi. On slow connections, client-side filtering can feel great after the first load, but that first load might be the slow part. Server-side filtering keeps payloads small, but it can feel laggy if you fire a request on every keypress.

Design around human input. Debounce requests during typing. For large result sets, use progressive loading so the page shows something quickly and stays smooth as the user scrolls.

Permissions should decide your filtering approach more than speed does. If the browser ever receives data a user is not allowed to see, you already have a problem, even if you hide it behind a disabled button or a collapsed column.

Start by naming what’s sensitive on this screen. Some fields are obvious (emails, phone numbers, addresses). Others are easy to overlook: internal notes, cost or margin, special pricing rules, risk scores, moderation flags.

The big trap is “we filter on the client, but only show allowed rows.” That still means the full dataset was downloaded. Anyone can inspect the network response, open dev tools, or save the payload. Hiding columns in the UI is not access control.

Server-side filtering is the safer default when authorization varies by user, especially when different users can see different rows or different fields.

Quick check:

If any answer is yes, keep filtering and field selection on the server. Send only what the user is allowed to see, and apply the same rules to search, sort, pagination, and export.

Example: in a CRM contact list, reps can view their own accounts while managers can view all. If the browser downloads all contacts and filters locally, a rep can still recover hidden accounts from the response. Server-side filtering prevents that by never sending those rows.

Caching can make a screen feel instant. It can also show the wrong truth. The key is deciding what you’re allowed to reuse, for how long, and what events must wipe it out.

Start by choosing the cache unit. Caching a full list is simple but usually wastes bandwidth and goes stale quickly. Caching pages works well for infinite scroll. Caching query results (filter + sort + search) is accurate, but can grow fast if users try many combinations.

Freshness matters more in some domains than others. If the data changes quickly (stock levels, balances, delivery status), even a 30-second cache can confuse users. If the data changes slowly (archived records, reference data), longer caching is usually fine.

Plan invalidation before you code. Besides time passing, decide what should force a refresh: creates/edits/deletes, permission changes, bulk imports or merges, status transitions, undo/rollback actions, and background jobs that update fields users filter on.

Also decide where caching lives. Browser memory makes back/forward navigation fast, but it can leak data across accounts if you don’t key it by user and org. Backend caching is safer for permissions and consistency, but it must include the full filter signature and caller identity so results don’t get mixed.

Treat the goal as non-negotiable: the screen should feel fast without leaking data.

Most teams get bitten by the same patterns: a UI that looks great in a demo, then real data, real permissions, and real network speeds expose the cracks.

The most serious failure is treating filtering as presentation. If the browser receives records it shouldn’t have, you already lost.

Two common causes:

Example: interns should only see leads from their region. If the API returns all regions and the dropdown filters in React, interns can still extract the full list.

Lag often comes from assumptions:

A subtle but painful problem is mismatched rules. If the server treats “starts with” differently than the UI, users see counts that don’t match, or items that disappear after refresh.

Do a final pass with two mindsets: a curious user and a bad network day.

A simple test: create a restricted record and confirm it never appears in the payload, counts, or cache, even when you filter broadly or clear filters.

Picture a CRM with 200,000 contacts. Sales reps can only see their own accounts, managers can see their team, and admins can see everything. The screen has search, filters (status, owner, last activity), and sorting.

Client-side filtering fails quickly here. The payload is heavy, the first load gets slow, and the risk of a data leak is high. Even if the UI hides rows, the browser still received the data. You also put pressure on the device: large arrays, heavy sorting, repeated filter runs, high memory use, and crashes on older phones.

A safer approach is server-side filtering with pagination. The client sends filter choices and search text, and the server returns only rows the user is allowed to see, already filtered and sorted.

A practical pattern:

A small exception where client-side filtering is fine: tiny, static data. A dropdown for “Contact status” with 8 values can be loaded once and filtered locally with little risk or cost.

Teams usually don’t get burned by choosing the “wrong” option once. They get burned by making a different choice on every screen, then trying to fix leaks and slow pages under pressure.

Write a short decision note per screen with filters: dataset size, what it costs to send, what “fast enough” feels like, which fields are sensitive, and how results should be cached (or not). Keep the server and UI aligned so you don’t end up with “two truths” for filtering.

If you’re building screens quickly in Koder.ai (koder.ai), it’s worth deciding up front which filters must be enforced on the backend (permissions and row-level access) and which small, UI-only toggles can stay in the React layer. That one choice tends to prevent the most expensive rewrites later.

Default to server-side when users have different permissions, the dataset is large, or you care about consistent pagination and totals. Use client-side only when the full dataset is small, safe to expose, and fast to download.

Because anything the browser receives can be inspected. Even if the UI hides rows or columns, a user can still see data in network responses, cached payloads, or in-memory objects.

It usually happens when you ship too much data and then filter/sort large arrays on every keystroke, or when you fire a server request for every keypress without debouncing. Keep payloads small and avoid doing heavy work on each input change.

Keep one source of truth for the “real” filters: permissions, search, sorting, and pagination should be enforced on the server together. Then limit client-side logic to small UI-only toggles that don’t change the underlying dataset.

Client-side caching can show stale or wrong data, and it can leak data across accounts if not keyed properly. Server-side caching is safer for permissions, but it must include the full filter signature and the caller identity so results don’t get mixed.

Ask two questions: how many rows could a user realistically have, and how large is each row in bytes. If you wouldn’t comfortably load it on a typical mobile connection or on an older device, move filtering to the server and paginate.

Server-side. If roles, teams, regions, or ownership rules change what someone can see, the server must enforce row and field access. The client should only receive records and fields the user is allowed to view.

Define the filter and sort contract first: accepted filter fields, default sorting, pagination rules, and how search matches (case, accents, partial matches). Then implement the same logic consistently on the backend and test that totals and pages match.

Debounce typing so you don’t request on every keypress, and keep old results visible until new results arrive to reduce flicker. Use pagination or progressive loading so the user sees something quickly without blocking on a huge response.

Apply permissions first, then filters and sorting, and return only one page plus a total count. Avoid sending “extra fields just in case,” and ensure caching keys include user/org/role so a rep never receives data meant for a manager.