Oct 06, 2025·7 min

Secure file uploads at scale: signed URLs and validation

Secure file uploads at scale with signed URLs, strict type and size checks, malware scanning, and permission rules that stay fast as traffic grows.

Secure file uploads at scale with signed URLs, strict type and size checks, malware scanning, and permission rules that stay fast as traffic grows.

File uploads look simple until real users show up. One person uploads a profile photo. Then ten thousand people upload PDFs, videos, and spreadsheets at the same time. Suddenly the app feels slow, storage costs jump, and support tickets pile up.

Common failure modes are predictable. Upload pages hang or time out when your server tries to handle the full file instead of letting object storage do the heavy lifting. Permissions drift, so someone guesses a file URL and sees something they shouldn’t. “Harmless” files arrive with malware, or with tricky formats that crash downstream tools. And logs are incomplete, so you can’t answer basic questions like who uploaded what and when.

What you want instead is boring and reliable: fast uploads, clear rules (allowed types and sizes), and an audit trail that makes incidents easy to investigate.

The hardest tradeoff is speed vs safety. If you run every check before the user can finish, they wait and retry, which increases load. If you postpone checks too much, unsafe or unauthorized files can spread before you catch them. A practical approach is to separate the upload from the checks, and keep each step quick and measurable.

Also be specific about “scale.” Write down your numbers: files per day, peak uploads per minute, max file size, and where your users are located. Regions matter for latency and privacy rules.

If you’re building an app on a platform like Koder.ai, it helps to decide these limits early, because they shape how you design permissions, storage, and the background scanning workflow.

Before you pick tools, get clear on what can go wrong. A threat model doesn’t need to be a big document. It’s a short, shared understanding of what you must prevent, what you can detect later, and what tradeoffs you’ll accept.

Attackers usually try to sneak in at a few predictable points: the client (changing metadata or faking MIME type), the network edge (replays and rate-limit abuse), storage (guessing object names, overwriting), and download/preview (triggering risky rendering or stealing files via shared access).

From there, map threats to simple controls:

Oversized files are the easiest abuse. They can run up costs and slow down real users. Stop them early with hard byte limits and fast rejection.

Fake file types come next. A file named invoice.pdf might be something else. Don’t trust extensions or UI checks. Verify based on the real bytes after upload.

Malware is different. You usually can’t scan everything before the upload completes without making the experience painful. The usual pattern is to detect it asynchronously, quarantine suspicious items, and block access until the scan passes.

Unauthorized access is often the most damaging. Treat every upload and every download as a permission decision. A user should only upload into a location they own (or are allowed to write to), and only download files they’re allowed to see.

For many apps, a solid v1 policy is:

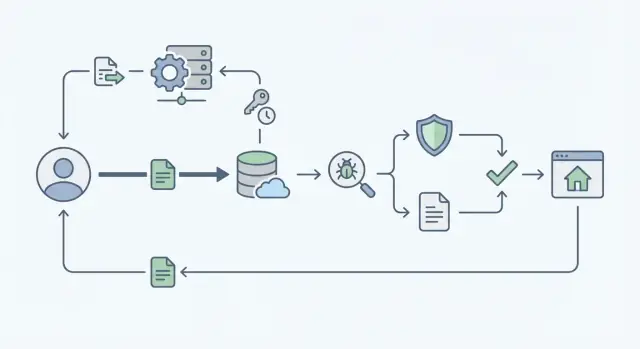

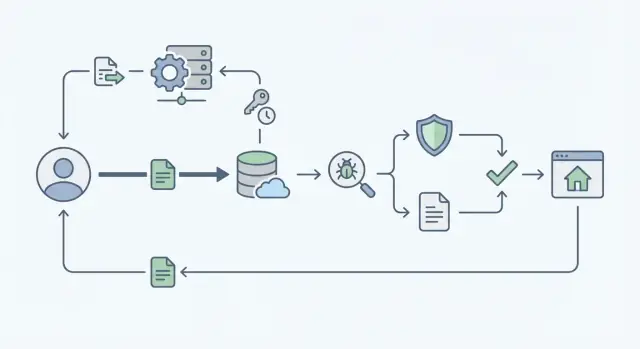

The fastest way to handle uploads is to keep your app server out of the “bytes business.” Instead of sending every file through your backend, let the client upload directly to object storage using a short-lived signed URL. Your backend stays focused on decisions and records, not pushing gigabytes.

The split is simple: the backend answers “who can upload what, and where,” while storage receives the file data. This removes a common bottleneck: app servers doing double work (auth plus proxying the file) and running out of CPU, memory, or network under load.

Keep a small upload record in your database (for example, PostgreSQL) so every file has a clear owner and a clear life cycle. Create this record before the upload starts, then update it as events happen.

Fields that usually pay off include owner and tenant/workspace identifiers, the storage object key, a status, claimed size and MIME type, and a checksum you can verify.

Treat uploads like a state machine so permission checks stay correct even when retries happen.

A practical set of states is:

Only allow the client to use the signed URL after the backend creates a requested record. After storage confirms the upload, move it to uploaded, kick off malware scanning in the background, and only expose the file once it’s approved.

Start when the user clicks Upload. Your app calls the backend to start an upload with basic details like filename, file size, and intended use (avatar, invoice, attachment). The backend checks permission for that specific target, creates an upload record, and returns a short-lived signed URL.

The signed URL should be narrowly scoped. Ideally it only allows a single upload to one exact object key, with a short expiry and clear conditions (size limit, allowed content type, optional checksum).

The browser uploads directly to storage using that URL. When it finishes, the browser calls the backend again to finalize. On finalize, re-check permission (users can lose access), and verify what actually landed in storage: size, detected content type, and checksum if you use one. Make finalize idempotent so retries don’t create duplicates.

Then mark the record as uploaded and trigger scanning in the background (queue/job). The UI can show “Processing” while the scan runs.

Relying on an extension is how invoice.pdf.exe ends up in your bucket. Treat validation as a repeatable set of checks that happens in more than one place.

Start with size limits. Put the maximum size into the signed URL policy (or pre-signed POST conditions) so storage can reject oversized uploads early. Enforce the same limit again when your backend records metadata, because clients can still try to bypass the UI.

Type checks should be based on content, not the filename. Inspect the first bytes of the file (magic bytes) to confirm it matches what you expect. A real PDF starts with %PDF, and PNG files begin with a fixed signature. If the content doesn’t match your allowlist, reject it even if the extension looks fine.

Keep allowlists specific to each feature. An avatar upload might only allow JPEG and PNG. A documents feature might allow PDF and DOCX. This cuts risk and makes your rules easier to explain.

Never trust the original filename as a storage key. Normalize it for display (remove odd characters, trim length), but store your own safe object key, like a UUID plus an extension you assign after type detection.

Store a checksum (like SHA-256) in your database and compare it later during processing or scanning. This helps catch corruption, partial uploads, or tampering, especially when uploads are retried under load.

Malware scanning matters, but it shouldn’t sit in the critical path. Accept the upload quickly, then treat the file as blocked until it passes a scan.

Create an upload record with a status like pending_scan. The UI can show the file, but it shouldn’t be usable yet.

Scanning is typically triggered by a storage event when the object is created, by publishing a job to a queue right after upload completion, or by doing both (queue plus storage event as a backstop).

The scan worker downloads or streams the object, runs scanners, then writes the result back to your database. Keep the essentials: scan status, scanner version, timestamps, and who requested the upload. That audit trail makes support much easier when someone asks, “Why was my file blocked?”

Don’t leave failed files mixed in with clean ones. Pick one policy and apply it consistently: quarantine and remove access, or delete if you don’t need it for investigation.

Whatever you choose, keep user messaging calm and specific. Tell them what happened and what to do next (re-upload, contact support). Alert your team if many failures happen in a short time.

Most importantly, set a strict rule for downloads and previews: only files marked approved can be served. Everything else returns a safe response like “File is still being checked.”

Fast uploads are great, but if the wrong person can attach a file to the wrong workspace, you have a bigger problem than slow requests. The simplest rule is also the strongest: every file record belongs to exactly one tenant (workspace/org/project) and has a clear owner or creator.

Do permission checks twice: when you issue a signed upload URL, and again when someone tries to download or view the file. The first check stops unauthorized uploads. The second check protects you if access is revoked, a URL leaks, or a user’s role changes after the upload.

Least privilege keeps both security and performance predictable. Instead of one broad “files” permission, separate roles like “can upload,” “can view,” and “can manage (delete/share).” Many requests then become quick lookups (user, tenant, action) instead of expensive custom logic.

To prevent ID guessing, avoid sequential file IDs in URLs and APIs. Use opaque identifiers and keep storage keys unguessable. Signed URLs are transport, not your permission system.

Shared files are where systems often get slow and messy. Treat sharing as explicit data, not implicit access. A simple approach is a separate sharing record that grants a user or group permission to one file, optionally with an expiry.

When people talk about scaling secure uploads, they often focus on security checks and forget the basics: moving bytes is the slow part. The goal is to keep large file traffic off your app servers, keep retries under control, and avoid turning safety checks into an unbounded queue.

For big files, use multipart or chunked uploads so a shaky connection doesn’t force users to restart from zero. Chunks also help you enforce clearer limits: maximum total size, maximum chunk size, and maximum upload time.

Set client timeouts and retries on purpose. A few retries can save real users; unlimited retries can blow up costs, especially on mobile networks. Aim for short per-chunk timeouts, a small retry cap, and a hard deadline for the whole upload.

Signed URLs keep the heavy data path fast, but the request that creates them is still a hot spot. Protect it so it stays responsive:

Latency also depends on geography. Keep your app, storage, and scanning workers in the same region when possible. If you need country-specific hosting for compliance, plan routing early so uploads don’t bounce across continents. Platforms that run on AWS globally (like Koder.ai) can place workloads closer to users when data residency matters.

Finally, plan downloads, not just uploads. Serve files with signed download URLs and set caching rules based on file type and privacy level. Public assets can be cached longer; private receipts should stay short-lived and permission-checked.

Picture a small business app where employees upload invoices and receipt photos, and a manager approves them for reimbursement. This is where upload design stops being academic: you have many users, large images, and real money on the line.

A good flow uses clear statuses so everyone knows what’s happening and you can automate the boring parts: the file lands in object storage and you save a record tied to the user/workspace/expense; a background job scans the file and extracts basic metadata (like real MIME type); then the item is either approved and becomes usable in reports, or rejected and blocked.

Users need fast, specific feedback. If the file is too big, show the limit and current size (for example: “File is 18 MB. Max is 10 MB.”). If the type is wrong, say what is allowed (“Upload a PDF, JPG, or PNG”). If scanning fails, keep it calm and actionable (“This file could be unsafe. Please upload a new copy.”).

Support teams need a trail that helps them debug without opening the file: upload ID, user ID, workspace ID, timestamps for created/uploaded/scan started/scan finished, result codes (too large, type mismatch, scan failed, permission denied), plus storage key and checksum.

Re-uploads and replacements are common. Treat them as new uploads, attach them to the same expense as a new version, keep history (who replaced it and when), and only mark the newest version as active. If you’re building this app on Koder.ai, this maps cleanly to an uploads table plus an expense_attachments table with a version field.

Most upload bugs aren’t fancy hacks. They’re small shortcuts that quietly turn into real risk when traffic grows.

More checks don’t have to make uploads slow. Separate the fast path from the heavy path.

Do quick checks synchronously (auth, size, allowed type, rate limits), then hand off scanning and deeper inspection to a background worker. Users can keep working while the file moves from “uploaded” to “ready.” If you’re building with a chat-based builder like Koder.ai, keep the same mindset: make the upload endpoint small and strict, and push scanning and post-processing into jobs.

Before you ship uploads, define what “safe enough for v1” means. Teams usually get into trouble by mixing strict rules (which block real users) with missing rules (which invite abuse). Start small, but make sure every upload has a clear path from “received” to “allowed to download.”

A tight pre-launch checklist:

If you need a minimum viable policy, keep it simple: size limit, narrow type allowlist, signed URL upload, and “quarantine until scan passes.” Add nicer features later (previews, more types, background reprocessing) once the core path is stable.

Monitoring is what keeps “fast” from turning into “mysteriously slow” as you grow. Track upload failure rate (client vs server/storage), scan failure rate and scan latency, average upload time by file-size bucket, authorization denials on download, and storage egress patterns.

Run a small load test with realistic file sizes and real-world networks (mobile data behaves differently from office Wi-Fi). Fix timeouts and retries before launch.

If you’re implementing this in Koder.ai (koder.ai), Planning Mode is a practical place to map your upload states and endpoints first, then generate the backend and UI around that flow. Snapshots and rollback can also help when you’re tuning limits or adjusting scan rules.

Use direct-to-object-storage uploads with short-lived signed URLs so your app servers don’t stream file bytes. Keep your backend focused on authorization decisions and recording upload state, not moving gigabytes.

Check twice: once when you create the upload and issue a signed URL, and again when you finalize and when you serve a download. Signed URLs are just a transport tool; your app still needs permission checks tied to the file record and its tenant/workspace.

Treat it as a state machine so retries and partial failures don’t create security gaps. A common flow is requested, uploaded, scanned, approved, rejected, and you only allow downloads when the status is approved.

Put a hard byte limit into the signed URL policy (or pre-signed POST conditions) so storage rejects oversized files early. Enforce the same limit again during finalize using storage-reported metadata so clients can’t bypass it.

Don’t trust the filename extension or browser MIME type. Detect type from the file’s actual bytes after upload (for example, magic bytes) and compare it to a tight allowlist for that specific feature.

Don’t block the user on scanning. Accept the upload quickly, quarantine it, run scanning in the background, and only allow download/preview after a clean result is recorded.

Pick a consistent policy: quarantine and remove access, or delete if you don’t need it for investigation. Give the user a calm, specific message and keep audit data so support can explain what happened without opening the file.

Never use the user-provided filename or path as the storage key. Generate an unguessable object key (like a UUID) and store the original name only as display metadata after normalizing it.

Use multipart or chunked uploads so unstable connections don’t restart from zero. Keep retries capped, set timeouts intentionally, and add a hard deadline for the whole upload so one client can’t tie up resources indefinitely.

Use a small upload record with owner, tenant/workspace, object key, status, timestamps, detected type, size, and checksum if you use one. If you build on Koder.ai, this fits well with a Go backend, PostgreSQL tables for uploads, and background jobs for scanning while keeping the UI responsive.