Aug 29, 2025·7 min

Safe third-party API integration: retries, timeouts, breakers

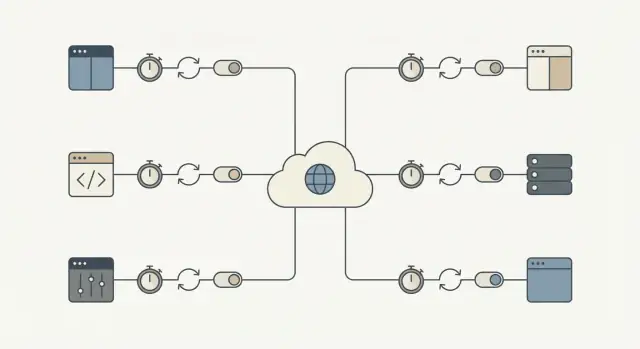

Safe third-party API integration that keeps your app running during outages. Learn timeouts, retries, circuit breakers, and quick checks.

Why third-party APIs can wedge your core workflows

A third-party API can fail in ways that don't look like a clean "down" event. The most common problem is slowness: requests hang, responses arrive late, and your app keeps waiting. If those calls sit on the critical path, a small hiccup outside your control piles up inside your system.

That's how a local slowdown becomes a full outage. Threads or workers get stuck waiting, queues grow, database transactions stay open longer, and new requests start timing out. Before long, even pages that don't use the external API feel broken because the system is overloaded by waiting work.

The impact is concrete. A flaky identity provider blocks signups and logins. A payment gateway timeout freezes checkout, leaving users unsure whether they were charged. A messaging delay stops password resets and order confirmations, which triggers a second wave of retries and support tickets.

The goal is simple: isolate external failures so core workflows keep moving. That might mean letting a user place an order while you confirm payment later, or allowing signup even if a welcome email fails.

A practical success metric: when a provider is slow or down, your app should still respond quickly and clearly, and the blast radius should stay small. For example, most core requests still finish within your normal latency budget, failures stay confined to features that truly depend on that API, users see a clear status (queued, pending, try again later), and recovery happens automatically when the provider returns.

The failure modes you should plan for

Most failures are predictable, even if their timing isn't. Name them up front and you can decide what to retry, what to stop, and what to show the user.

The common categories:

- Latency spikes (requests that suddenly take 10x longer)

- Transient server or network errors (timeouts, 502/503, connection resets)

- Rate limits and quota exhaustion (429s, daily caps)

- Auth and permission problems (expired keys, revoked access)

- Bad or surprising data (missing fields, wrong formats, partial responses)

Not all errors mean the same thing. Transient issues are often worth retrying because the next call may succeed (network blips, timeouts, 502/503, and some 429s after waiting). Permanent issues usually won't fix themselves (invalid credentials, wrong endpoints, malformed requests, permission denials).

Treating every error the same turns a small incident into downtime. Retrying permanent failures wastes time, hits rate limits faster, and builds a backlog that slows everything else. Never retrying transient failures forces users to repeat actions and drops work that could have completed moments later.

Pay extra attention to workflows where a pause feels like a break: checkout, login, password reset, and notifications (email/SMS/push). A two-second spike in a marketing API is annoying. A two-second spike in payment authorization blocks revenue.

A helpful test is: "Is this call required to finish the user's main task right now?" If yes, you need tight timeouts, careful retries, and a clear failure path. If no, shift it to a queue and keep the app responsive.

Timeouts: pick a limit and stick to it

A timeout is the maximum time you're willing to wait before you stop and move on. Without a clear limit, one slow provider can pile up waiting requests and block important work.

It helps to separate two kinds of waiting:

- Connect timeout: how long you'll try to establish a connection.

- Read timeout: how long you'll wait for a response after connecting.

Picking numbers isn't about perfection. It's about matching human patience and your workflow.

- If a user is staring at a spinner, you usually need a fast answer and a clear next step.

- If it's a background job (like syncing invoices overnight), you can allow more time, but it still needs a ceiling so it can't hang forever.

A practical way to choose timeouts is to work backward from the experience:

- How long can a user wait before you need to show a clear message?

- If this call fails now, can you retry later or use a fallback?

- How many of these calls run at peak load?

The tradeoff is real. Too long and you tie up threads, workers, and database connections. Too short and you create false failures and trigger unnecessary retries.

Retries that don't make outages worse

Retries help when a failure is likely temporary: a brief network issue, DNS hiccup, or a one-off 500/502/503. In those cases, a second try can succeed and users never notice.

The risk is a retry storm. When many clients fail at once and all retry together, they can overload the provider (and your own workers). Backoff and jitter prevent that.

A retry budget keeps you honest. Keep attempts low and cap total time so core workflows don't get stuck waiting on someone else.

A safe default retry recipe

- Retry only a few times (often 1-3 attempts total, depending on the flow).

- Use exponential backoff (for example 200ms, 500ms, 1s) plus random jitter.

- Cap total time spent retrying (often a few seconds in user-facing flows).

- Use a per-attempt timeout instead of one long timeout for all attempts.

Don't retry predictable client errors like 400/422 validation issues, 401/403 auth problems, or 404s. Those will almost always fail again and just add load.

One more guardrail: only retry writes (POST/PUT) when you have idempotency in place, otherwise you risk double charges or duplicate records.

Idempotency: make retries safe for real workflows

Idempotency means you can safely run the same request twice and end up with the same final result. That matters because retries are normal: networks drop, servers restart, and clients time out. Without idempotency, a "helpful" retry creates duplicates and real money problems.

Picture checkout: the payment API is slow, your app times out, and you retry. If the first call actually succeeded, the retry might create a second charge. The same risk shows up in actions like creating an order, starting a subscription, sending an email/SMS, issuing a refund, or creating a support ticket.

The fix is to attach an idempotency key (or request ID) to every "do something" call. It should be unique per user action, not per attempt. The provider (or your own service) uses that key to detect duplicates and return the same outcome instead of performing the action again.

Treat the idempotency key like part of the data model, not a header you hope nobody forgets.

A pattern that holds up in production

Generate one key when the user starts the action (for example, when they click Pay), then store it with your local record.

On every attempt:

- Send the same key.

- Store the final result you got back (success response, failure code, charge ID).

- If you already have a recorded outcome, return that outcome instead of repeating the action.

If you're the "provider" for internal calls, enforce the same behavior server-side.

Circuit breakers: stop calling the API when it's failing

Decide what must be synchronous

Use Planning Mode to map must-have vs can-wait calls before you implement anything.

A circuit breaker is a safety switch. When an external service starts failing, you stop calling it for a short period instead of piling on more requests that will likely time out.

Circuit breakers usually have three states:

- Closed: requests flow normally.

- Open: calls are blocked for a cooldown window.

- Half-open: after the cooldown, a small number of test calls check whether the service recovered.

When the breaker is open, your app should do something predictable. If an address validation API is down during signup, accept the address and mark it for later review. If a payment risk check is down, queue the order for manual review or temporarily disable that option and explain it.

Pick thresholds that match user impact:

- consecutive errors (for example 5 failures in a row)

- high failure rate over a short window

- many slow responses (timeouts)

- specific status codes (like repeated 503s)

Keep cooldowns short (seconds to a minute) and keep half-open probes limited. The goal is to protect core workflows first, then recover quickly.

Fallbacks and queues: keep the app usable

When an external API is slow or down, your goal is to keep the user moving. That means having a Plan B that's honest about what happened.

Fallbacks: choose a "good enough" experience

A fallback is what your app does when the API can't respond in time. Options include using cached data, switching to a degraded mode (hide non-essential widgets, disable optional actions), asking for user input instead of calling the API (manual address entry), or showing a clear message with the next step.

Be honest: don't say something completed if it didn't.

Queues: do it later when "now" isn't required

If the work doesn't need to finish inside the user request, push it to a queue and respond quickly. Common candidates: sending emails, syncing to a CRM, generating reports, and posting analytics events.

Fail fast for core actions. If an API isn't required to complete checkout (or account creation), don't block the request. Accept the order, queue the external call, and reconcile later. If the API is required (for example payment authorization), fail quickly with a clear message and don't keep the user waiting.

What the user sees should match what happens behind the scenes: a clear status (completed, pending, failed), a promise you can keep (receipt now, confirmation later), a way to retry, and a visible record in the UI (activity log, pending badge).

Rate limits and load: avoid self-inflicted failures

Rate limits are a provider's way of saying, "You can call us, but not too often." You'll hit them sooner than you think: traffic spikes, background jobs firing together, or a bug that loops on errors.

Start by controlling how many requests you create. Batch when possible, cache responses even for 30 to 60 seconds when it's safe, and throttle on the client side so your app never bursts faster than the provider allows.

When you get a 429 Too Many Requests, treat it as a signal to slow down.

- Respect

Retry-Afterwhen it's provided. - Add jitter so many workers don't retry at the same moment.

- Cap retries for 429s to avoid endless loops.

- Back off more aggressively on repeated 429s.

- Record it as a metric so you notice patterns before users do.

Also limit concurrency. A single workflow (like syncing contacts) shouldn't consume every worker slot and starve critical flows like login or checkout. Separate pools or per-feature caps help.

Step-by-step: a safe default integration recipe

Standardize your integration defaults

Generate a consistent timeout and retry budget you can reuse across services.

Every third-party call needs a plan for failure. You don't need perfection. You need predictable behavior when the provider has a bad day.

1) Classify the call (must-have vs can-wait)

Decide what happens if the call fails right now. A tax calculation during checkout might be must-have. Syncing a marketing contact can usually wait. This choice drives the rest.

2) Set timeouts and a retry budget

Pick timeouts per call type and keep them consistent. Then set a retry budget so you don't keep hammering a slow API.

- Must-have, user waiting: short timeout, 0-1 retry.

- Can-wait, background job: longer timeout, a few retries with backoff.

- Never retry forever: cap total time spent per task.

3) Make retries safe with idempotency and tracking

If a request can create something or charge money, add idempotency keys and store a request record. If a payment request times out, a retry should not double-charge. Tracking also helps support answer, "Did it go through?"

4) Add a circuit breaker and fallback behavior

When errors spike, stop calling the provider for a short period. For must-have calls, show a clear "Try again" path. For can-wait calls, queue the work and process it later.

5) Monitor the basics

Track latency, error rate, and breaker open/close events. Alert on sustained changes, not single blips.

Common mistakes that turn a small issue into downtime

Most API outages don't start big. They become big because your app reacts in the worst possible way: it waits too long, retries too aggressively, and ties up the same workers that keep everything else running.

These patterns cause cascades:

- Retrying every failure, including 4xx problems like invalid requests, expired auth, or missing permissions.

- Setting very long timeouts "to be safe," which quietly consumes threads, DB connections, or job runners until you run out of capacity.

- Retrying create actions without idempotency keys, leading to double charges, duplicate shipments, or repeated records.

- Misconfigured circuit breakers that never recover or flap open and closed.

- Treating partial outages as total failure instead of degrading only the affected feature.

Small fixes prevent big outages: retry only errors likely to be temporary (timeouts, some 429s, some 5xx) and cap attempts with backoff and jitter; keep timeouts short and intentional; require idempotency for any operation that creates or charges; and design for partial outages.

Quick checklist before you ship

Queue the work that can wait

Move non-critical API calls into a queue so user requests finish fast.

Before you push an integration to production, do a quick pass with a failure mindset. If you can't answer "yes" to an item, treat it as a release blocker for core workflows like signup, checkout, or sending messages.

- Time limits are explicit (connect timeout and read/response timeout).

- Retries are limited (small retry budget, backoff, jitter, and a total time cap).

- Retries are safe for real actions (idempotency keys or clear dedupe checks).

- There's a breaker and a plan B (fallback, degraded mode, or a queue).

- You can see problems early (latency, error rate, and dependency health per provider and endpoint).

If a payment provider starts timing out, the right behavior is "checkout still loads, the user gets a clear message, and you don't spin forever," not "everything hangs until it times out."

Example: protecting checkout when a provider is flaky

Imagine a checkout that calls three services: a payment API to charge the card, a tax API to calculate tax, and an email API to send the receipt.

The payment call is the only one that must be synchronous. Problems in tax or email shouldn't wedge the purchase.

When the tax API is slow

Say the tax API sometimes takes 8 to 15 seconds. If checkout waits, users abandon carts and your app ties up workers.

A safer flow:

- Set a hard timeout (for example 800ms to 2s) and fail fast.

- Retry at most once, only if it's safe, with jitter.

- If timeout hits, use a cached rate or last-known table for the buyer's region.

- If you can't legally use cached rates, place the order as "pending tax" and queue a recalculation.

Outcome: fewer abandoned carts and fewer stuck orders when the tax provider is slow.

When the email API is down

Receipt email matters, but it should never block payment capture. If the email API is failing, the circuit breaker should open after a few quick failures and stop calls for a short cooldown window.

Instead of sending email inline, enqueue a "send receipt" job with an idempotency key (for example order_id + email_type). If the provider is down, the queue retries in the background and the customer still sees a successful purchase.

Outcome: fewer support tickets from missing confirmations, and no lost revenue from checkout failing for non-payment reasons.

Next steps: roll this out safely across your app

Pick one workflow that hurts the most when it breaks (checkout, signup, invoicing) and make it your reference integration. Then copy the same defaults everywhere.

A simple rollout order:

- Set timeouts and fail fast with a clear error.

- Add retries with backoff, but only for retryable errors.

- Add idempotency so retries don't double-charge or double-create.

- Add circuit breakers so a bad provider can't wedge your core workflow.

Write down your defaults and keep them boring: one connect timeout, one request timeout, max retry count, backoff range, breaker cooldown, and the rules for what's retryable.

Run a failure drill before expanding to the next workflow. Force timeouts (or block the provider in a test environment), then confirm the user sees a useful message, fallback paths work, and queued retries don't pile up forever.

If you're building new products quickly, it's worth turning these reliability defaults into a reusable template. For teams using Koder.ai (koder.ai), that often means defining the timeout, retry, idempotency, and breaker rules once, then applying the same pattern across new services as you generate and iterate.