Dec 23, 2025·7 min

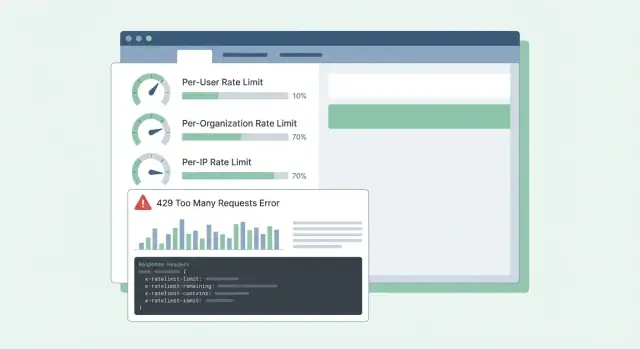

SaaS API rate limiting: per-user, org, and IP patterns

SaaS API rate limiting patterns for per-user, per-org, and per-IP limits, with clear headers, error bodies, and rollout tips customers understand.

SaaS API rate limiting patterns for per-user, per-org, and per-IP limits, with clear headers, error bodies, and rollout tips customers understand.

Rate limits and quotas sound similar, so people often treat them as the same thing. A rate limit is how fast you can call an API (requests per second or per minute). A quota is how much you can use over a longer period (per day, per month, or per billing cycle). Both are normal, but they feel random when the rules aren’t visible.

The classic complaint is: “it worked yesterday.” Usage is rarely steady. A short spike can push someone over the line even if their daily total looks fine. Imagine a customer who runs a report once a day, but today the job retries after a timeout and makes 10x more calls in 2 minutes. The API blocks them, and all they see is a sudden failure.

Confusion gets worse when errors are vague. If the API returns 500 or a generic message, customers assume your service is down, not that they hit a limit. They open urgent tickets, build workarounds, or switch providers. Even 429 Too Many Requests can be frustrating if it doesn’t say what to do next.

Most SaaS APIs limit traffic for two different reasons:

Mixing these goals leads to bad designs. Abuse controls are often per-IP or per-token and can be strict. Normal usage shaping is usually per-user or per-organization and should come with clear guidance: what limit was hit, when it resets, and how to avoid hitting it again.

When customers can predict limits, they plan around them. When they can’t, every spike feels like a broken API.

Rate limits aren’t just a throttle. They’re a safety system. Before you pick numbers, be clear about what you’re trying to protect, because each goal leads to different limits and different expectations.

Availability is usually first. If a few clients can spike traffic and push your API into timeouts, everyone suffers. Limits here should keep servers responsive during bursts and fail fast instead of letting requests pile up.

Cost is the quiet driver behind many APIs. Some requests are cheap, others are expensive (LLM calls, file processing, storage writes, paid third-party lookups). For example, on a platform like Koder.ai, a single user can trigger many model calls through chat-based app generation. Limits that track expensive actions can prevent surprise bills.

Abuse looks different from high legitimate usage. Credential stuffing, token guessing, and scraping often show up as many small requests from a narrow set of IPs or accounts. Here you want strict limits and quick blocking.

Fairness matters in multi-tenant systems. One noisy customer shouldn’t degrade everyone else. In practice, that often means layering controls: a burst guard to keep the API healthy minute to minute, a cost guard for expensive endpoints or actions, an abuse guard focused on auth and suspicious patterns, and a fairness guard so one org can’t crowd out others.

A simple test helps: pick one endpoint and ask, “If this request increases 10x, what breaks first?” The answer tells you which protection goal to prioritize, and which dimension (user, org, IP) should carry the limit.

Most teams start with one limit and later discover it hurts the wrong people. The goal is to pick dimensions that match real usage: who is calling, who is paying, and what looks like abuse.

Common dimensions in SaaS look like this:

Per-user limits are about fairness inside a tenant. If one person runs a big export, they should feel the slowdown more than the rest of the team.

Per-org limits are about budget and capacity. Even if ten users all run jobs at once, the org shouldn’t spike to a level that breaks your service or your pricing assumptions.

Per-IP limits are best treated as a safety net, not a billing tool. IPs can be shared (office NAT, mobile carriers), so keep these limits generous and rely on them mainly to stop obvious abuse.

When you combine dimensions, decide which one “wins” when multiple limits apply. A practical rule is: reject the request if any relevant limit is exceeded, and return the most actionable reason. If a workspace is over its org quota, don’t blame the user or the IP.

Example: a Koder.ai workspace on a Pro plan might allow a steady flow of build requests per org, while also limiting a single user from firing hundreds of requests in a minute. If a partner integration uses one shared token, a per-token limit can stop it from drowning out interactive users.

Most rate limiting problems aren’t about math. They’re about choosing behavior that matches how customers call your API, then keeping it predictable under load.

Token bucket is a common default because it allows short bursts while enforcing a steady long-term average. A user who refreshes a dashboard might trigger 10 quick requests. Token bucket lets that happen if they’ve saved up tokens, then slows them back down.

Leaky bucket is stricter. It smooths traffic into a constant outflow, which helps when your backend can’t handle spikes (for example, expensive report generation). The tradeoff is that customers feel it sooner, because bursts turn into queueing or rejection.

Window-based counters are simple, but details matter. Fixed windows create sharp edges at the boundary (a user can burst at 12:00:59 and again at 12:01:00). Sliding windows feel fairer and reduce boundary spikes, but need more state or better data structures.

A separate class of limit is concurrency (in-flight requests). This protects you from slow client connections and long-running endpoints. A customer might stay within 60 requests per minute but still overload you by keeping 200 requests open at once.

In real systems, teams often combine a small set of controls: a token bucket for general request rate, a concurrency cap for slow or heavy endpoints, and separate budgets for endpoint groups (cheap reads vs costly exports). If you only limit by request count, one expensive endpoint can crowd out everything else and make the API feel randomly broken.

Good quotas feel fair and predictable. Customers shouldn’t discover the rules only after getting blocked.

Keep the separation clear:

Many SaaS teams use both: a short rate limit to stop bursts plus a monthly quota tied to pricing.

Hard vs soft limits is mostly a support choice. A hard limit blocks immediately. A soft limit warns first, then blocks later. Soft limits reduce angry tickets because people get a chance to fix a bug or upgrade before an integration breaks.

When someone goes over, the behavior should match what you’re protecting. Blocking works when overuse could hurt other tenants or explode costs. Degrading (slower processing or lower priority) works when you’d rather keep things moving. “Bill later” can work when usage is predictable and you already have a billing flow.

Tier-based limits work best when each tier has a clear “expected usage shape.” A free tier might allow small monthly quotas and low burst rates, while business and enterprise tiers get higher quotas and higher burst limits so background jobs can finish quickly. That’s similar to how Koder.ai’s free, pro, business, and enterprise tiers set different expectations for how much you can do before moving up.

Custom limits are worth supporting early, especially for enterprise. A clean approach is “defaults by plan, overrides by customer.” Store an admin-set override per org (and sometimes per endpoint) and make sure it survives plan changes. Also decide who can request changes and how quickly they take effect.

Example: a customer imports 50,000 records on the last day of the month. If their monthly quota is nearly used up, a soft warning at 80-90% gives them time to pause. A short per-second rate limit prevents the import from flooding the API. An approved org override (temporary or permanent) keeps the business moving.

Start by writing down what you will count and who it belongs to. Most teams end up with three identities: the signed-in user, the customer org (or workspace), and the client IP.

A practical plan:

When you set limits, think in tiers and endpoint groups, not one global number. One common failure is relying on in-memory counters across multiple app servers. Counters disagree, and users see “random” 429s. A shared store like Redis keeps limits stable across instances, and TTLs keep data small.

Rollout matters. Start in “report only” mode (log what would have been blocked), then enforce one endpoint group, then expand. That’s how you avoid waking up to a wall of support tickets.

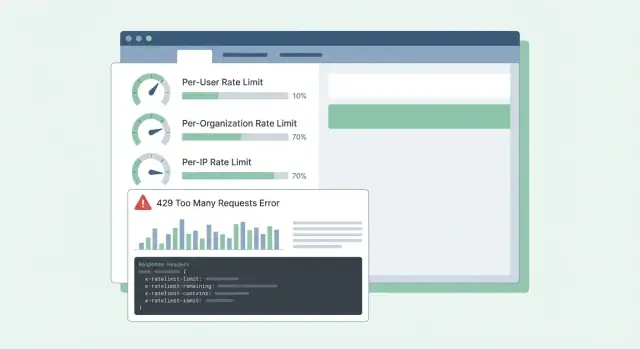

When a customer hits a limit, the worst outcome is confusion: “Is your API down, or did I do something wrong?” Clear, consistent responses cut support tickets and help people fix client behavior.

Use HTTP 429 Too Many Requests when you’re actively blocking calls. Keep the response body predictable so SDKs and dashboards can read it.

Here’s a simple JSON shape that works well across per-user, per-org, and per-IP limits:

{

"error": {

"code": "rate_limit_exceeded",

"message": "Rate limit exceeded for org. Try again later.",

"limit_scope": "org",

"reset_at": "2026-01-17T12:34:56Z",

"request_id": "req_01H..."

}

}

Headers should explain the current window and what the client can do next. If you only add a few, start here: RateLimit-Limit, RateLimit-Remaining, RateLimit-Reset, Retry-After, and X-Request-Id.

Example: a customer’s cron job runs every minute and suddenly starts failing. With 429 plus RateLimit-Remaining: 0 and Retry-After: 20, they immediately know it’s a limit, not an outage, and they can delay retries by 20 seconds. If they share X-Request-Id with support, you can find the event quickly.

One more detail: return the same headers on successful requests too. Customers can see they’re getting close to the edge before they hit it.

Good clients make limits feel fair. Bad clients turn a temporary limit into an outage by hammering harder.

When you get a 429, treat it as a signal to slow down. If the response tells you when to try again (for example, via Retry-After), wait at least that long. If it doesn’t, use exponential backoff and add jitter (randomness) so a thousand clients don’t retry at the same moment.

Keep retries bounded: cap the delay between attempts (for example, 30-60 seconds) and cap the total retry time (for example, stop after 2 minutes and surface an error). Also log the event with limit details so developers can tune later.

Don’t retry everything. Many errors won’t succeed without a change or user action: 400 validation errors, 401/403 auth errors, 404 not found, and 409 conflicts that reflect a real business rule.

Retries are risky on write endpoints (create, charge, send email). If a timeout happens and the client retries, you can create duplicates. Use idempotency keys: the client sends a unique key per logical action, and the server returns the same result for repeats of that key.

Good SDKs can make this easier by surfacing what developers actually need: status (429), how long to wait, whether the request is safe to retry, and a message like “Rate limit exceeded for org. Retry after 8s or reduce concurrency.”

Most support tickets about limits aren’t about the limit itself. They’re about surprises. If users can’t predict what will happen next, they assume the API is broken or unfair.

Using only IP-based limits is a frequent mistake. Many teams sit behind one public IP (office Wi-Fi, mobile carriers, cloud NAT). If you cap by IP, one busy customer can block everyone else on the same network. Prefer per-user and per-org limits, and use per-IP mainly as an abuse safety net.

Another issue is treating all endpoints as equal. A cheap GET and a heavy export job shouldn’t share the same budget. Otherwise customers burn through their allowance doing normal browsing, then get blocked when they try a real task. Separate buckets by endpoint group or weight requests by cost.

Reset timing also needs to be explicit. “Resets daily” isn’t enough. Which time zone? Rolling window or midnight reset? If you do calendar resets, say the time zone. If you do rolling windows, say the window length.

Finally, vague errors create chaos. Returning 500 or generic JSON makes people retry harder. Use 429 and include RateLimit headers so clients can back off intelligently.

Example: if a team builds a Koder.ai integration from a shared corporate network, an IP-only cap can block their whole org and look like random outages. Clear dimensions and clear 429 responses prevent that.

Before you turn on limits for everyone, do a final pass that focuses on predictability:

A gut check: if your product has tiers like Free, Pro, Business, and Enterprise (like Koder.ai), you should be able to explain in plain language what a normal customer can do per minute and per day, and which endpoints are treated differently.

If you can’t explain a 429 clearly, customers will assume the API is broken, not protecting the service.

Picture a B2B SaaS where people work inside a workspace (org). A few power users run heavy exports, and many employees sit behind one shared office IP. If you only limit by IP, you block whole companies. If you only limit by user, a single script can still hurt the whole workspace.

A practical mix is:

When someone hits a limit, your message should tell them what happened, what to do next, and when to retry. Support should be able to stand behind wording like:

“Request rate exceeded for workspace ACME. You can retry after 23 seconds. If you are running an export, reduce concurrency to 2 or schedule it off-peak. If this blocks normal use, reply with your workspace ID and timestamp and we can review your quota.”

Pair that message with Retry-After and consistent RateLimit headers so customers don’t have to guess.

A rollout that avoids surprises: observe-only first, then warn (headers and soft warnings), then enforce (429s with clear retry timing), then tune thresholds per tier, then review after big launches and customer onboardings.

If you want a fast way to turn these ideas into working code, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai (koder.ai) can help you draft a short rate limit spec and generate Go middleware that enforces it consistently across services.

A rate limit caps how fast you can make requests, like requests per second or per minute. A quota caps how much you can use over a longer period, like per day, per month, or per billing cycle.

If you want fewer “it worked yesterday” surprises, show both clearly and make the reset timing explicit so customers can predict behavior.

Start with the failure you’re preventing. If bursts cause timeouts, you need a short-term burst control; if certain endpoints drive spend, you need a cost-based budget; if you’re seeing brute force or scraping, you need strict abuse controls.

A quick way to decide is to ask: “If this one endpoint gets 10× traffic, what breaks first: latency, cost, or security?” Then design the limit around that.

Use per-user limits to keep one person from slowing down their teammates, and per-org limits to keep a whole workspace within a predictable ceiling that matches pricing and capacity. Add per-token limits when a shared integration key could drown out interactive users.

Treat per-IP limits as a safety net for obvious abuse, because shared networks can make IP-based limits block innocent users.

Token bucket is a good default when you want to allow brief bursts but enforce a steady average over time. It fits common UX patterns like dashboards that fire several requests at once.

If your backend can’t tolerate spikes at all, a stricter approach like leaky bucket or explicit queuing may feel more consistent, but it will be less forgiving during bursts.

Add a concurrency limit when the damage comes from too many in-flight requests rather than request count. This is common with slow endpoints, long polling, streaming, large exports, or clients with poor network conditions.

Concurrency caps prevent a client from “staying within 60 requests/minute” while still tying up hundreds of open connections.

Return HTTP 429 when you are actively throttling, and include a clear error body that says which scope was hit (user, org, IP, or token) and when the client can try again. The single most helpful header is Retry-After, because it tells clients exactly how long to wait.

Also return rate limit headers on successful requests so customers can see they’re approaching the edge before they get blocked.

A simple default is: if Retry-After is present, wait at least that long before retrying. If it’s not present, use exponential backoff with a bit of randomness so many clients don’t retry at the same moment.

Keep retries bounded, and don’t blindly retry errors that won’t succeed without changes, especially auth and validation failures.

Use hard limits when going over would harm other customers or trigger immediate costs you can’t absorb. Use soft limits when you want to warn first, give time to fix a bug, or allow an upgrade before blocking.

A practical pattern is warning at a threshold like 80–90% usage, then enforcing later, so you reduce urgent support tickets without letting runaway usage continue indefinitely.

Keep IP limits generous and primarily aimed at abuse patterns, because many real companies share one public IP behind NAT, office Wi‑Fi, or mobile carriers. If you set strict per-IP caps, you can accidentally block an entire customer when one script misbehaves.

For normal usage shaping, prefer per-user and per-org limits, and only use per-IP as a backstop.

Roll out in stages so you can see impact before customers feel pain. Start with “report only” logging to measure what would be blocked, then enforce on a small set of endpoints or a subset of tenants, and only then expand.

Watch for spikes in 429s, increased latency from the limiter, and the top identities being blocked; those signals tell you where thresholds or dimensions are wrong before it turns into a support flood.