Oct 14, 2025·8 min

PostgreSQL row-level security for SaaS: policies that work

PostgreSQL row-level security for SaaS helps enforce tenant isolation in the database. Learn when to use it, how to write policies, and what to avoid.

PostgreSQL row-level security for SaaS helps enforce tenant isolation in the database. Learn when to use it, how to write policies, and what to avoid.

In a SaaS app, the most dangerous security bug is the one that shows up after you scale. You start with a simple rule like “users can only see their tenant’s data,” then you ship a new endpoint quickly, add a reporting query, or introduce a join that quietly skips the check.

App-only authorization breaks under pressure because the rules end up scattered. One controller checks tenant_id, another checks membership, a background job forgets, and an “admin export” path stays “temporary” for months. Even careful teams miss a spot.

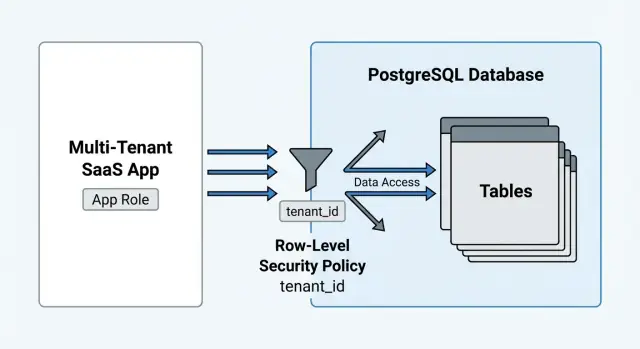

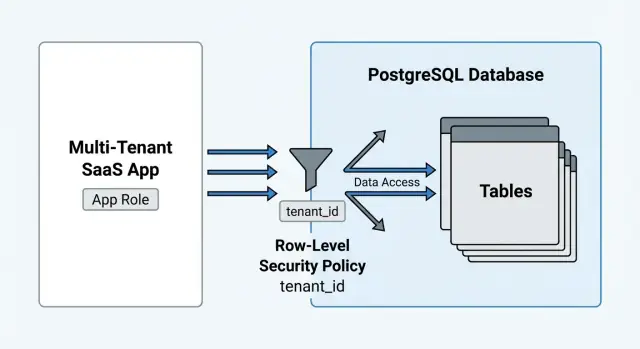

PostgreSQL row-level security (RLS) solves a specific problem: it makes the database enforce which rows are visible for a given request. The mental model is simple: every SELECT, UPDATE, and DELETE is automatically filtered by policies, the way every request is filtered by authentication middleware.

The “rows” part matters. RLS doesn’t protect everything:

A concrete example: you add an endpoint that lists projects with a join to invoices for a dashboard. With app-only auth, it’s easy to filter projects by tenant but forget to filter invoices, or to join on a key that crosses tenants. With RLS, both tables can enforce tenant isolation, so the query fails safe instead of leaking data.

The trade-off is real. You write less repeated authorization code and reduce the number of places that can leak. But you also take on new work: you must design policies carefully, test them early, and accept that a policy can block a query you expected to work.

RLS can feel like extra work until your app grows past a handful of endpoints. If you have strict tenant boundaries and lots of query paths (list screens, search, exports, admin tools), putting the rule in the database means you don’t have to remember to add the same filter everywhere.

RLS is a strong fit when the rule is boring and universal: “a user can only see rows for their tenant” or “a user can only see projects they’re a member of.” In those setups, policies reduce mistakes because every SELECT, UPDATE, and DELETE goes through the same gate, even when a query is added later.

It also helps in read-heavy apps where filtering logic stays consistent. If your API has 15 different ways to load invoices (by status, by date, by customer, by search), RLS lets you stop re-implementing tenant filtering on every query and focus on the feature.

RLS adds pain when the rules aren’t row-based. Per-field rules like “you can see salary but not bonus” or “mask this column unless you are HR” often turn into awkward SQL and hard-to-maintain exceptions.

It’s also a rough fit for heavy reporting that genuinely needs broad access. Teams often create bypass roles for “just this one job,” and that’s where mistakes pile up.

Before you commit, decide whether you want the database to be the final gatekeeper. If yes, plan for the discipline: test database behavior (not only API responses), treat migrations as security changes, avoid quick bypasses, decide how background jobs authenticate, and keep policies small and repeatable.

If you use tooling that generates backends, it can speed up delivery, but it doesn’t remove the need for clear roles, tests, and a simple tenant model. (For example, Koder.ai uses Go and PostgreSQL for generated backends, and you still want to design RLS deliberately rather than “sprinkle it in later.”)

RLS is easiest when your schema already says, clearly, who owns what. If you start with a fuzzy model and try to “fix it in policies,” you usually get slow queries and confusing bugs.

Pick one tenant key (like org_id) and use it consistently. Most tenant-owned tables should have it, even if they also reference another table that has it. This avoids joins inside policies and keeps USING checks simple.

A practical rule: if a row should disappear when a customer cancels, it probably needs org_id.

RLS policies usually answer one question: “Is this user a member of this org, and what can they do?” That’s hard to infer from ad hoc columns.

Keep the core tables small and boring:

users (one row per person)orgs (one row per tenant)org_memberships (user_id, org_id, role, status)project_memberships for per-project accessWith that in place, your policies can check membership with one indexed lookup.

Not everything needs org_id. Reference tables like countries, product categories, or plan types are often shared across all tenants. Make them read-only for most roles, and don’t tie them to one org.

Tenant-owned data (projects, invoices, tickets) should avoid pulling in tenant-specific details through shared tables. Keep shared tables minimal and stable.

Foreign keys still work with RLS, but deletes can surprise you if the deleting role can’t “see” dependent rows. Plan cascades carefully and test real delete flows.

Index the columns your policies filter on, especially org_id and membership keys. A policy that reads like “WHERE org_id = ...” shouldn’t become a full-table scan when the table hits millions of rows.

RLS is a per-table switch. Once enabled, PostgreSQL stops trusting your app code to remember the tenant filter. Every SELECT, UPDATE, and DELETE is filtered by policies, and every INSERT and UPDATE is validated by policies.

The biggest mental shift: with RLS on, queries that used to return data can start returning zero rows without errors. That’s PostgreSQL doing access control.

Policies are small rules attached to a table. They use two checks:

USING is the read filter. If a row doesn’t match USING, it’s invisible for SELECT, and it can’t be targeted by UPDATE or DELETE.WITH CHECK is the write gate. It decides what new or changed rows are allowed for INSERT or UPDATE.A common SaaS pattern: USING ensures you only see rows from your tenant, and WITH CHECK ensures you can’t insert a row into someone else’s tenant by guessing a tenant ID.

When you add more policies later, this matters:

PERMISSIVE (default): a row is allowed if any policy allows it.RESTRICTIVE: a row is allowed only if all restrictive policies allow it (on top of permissive behavior).If you plan to layer rules like tenant match plus role checks plus project membership, restrictive policies can make intent clearer, but they also make it easier to lock yourself out if you forget one condition.

RLS needs a reliable “who is calling” value. Common options:

app.user_id and app.tenant_id).SET ROLE ... per request), which can work but adds operational overhead.Pick one approach and apply it everywhere. Mixing identity sources across services is a fast path to confusing bugs.

Use a predictable convention so schema dumps and logs stay readable. For example: {table}__{action}__{rule}, like projects__select__tenant_match.

If you’re new to RLS, start with one table and a small proof. The goal isn’t perfect coverage. The goal is to make the database refuse cross-tenant access even when an app bug happens.

Assume a simple projects table. First, add tenant_id in a way that won’t break writes.

ALTER TABLE projects ADD COLUMN tenant_id uuid;

-- Backfill existing rows (example: everyone belongs to a default tenant)

UPDATE projects SET tenant_id = '11111111-1111-1111-1111-111111111111'::uuid

WHERE tenant_id IS NULL;

ALTER TABLE projects ALTER COLUMN tenant_id SET NOT NULL;

Next, separate ownership from access. A common pattern is: one role owns tables (app_owner), another role is used by the API (app_user). The API role should not be the table owner, or it can bypass policies.

ALTER TABLE projects OWNER TO app_owner;

REVOKE ALL ON projects FROM PUBLIC;

GRANT SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE ON projects TO app_user;

Now decide how the request tells Postgres which tenant it is serving. One simple approach is a request-scoped setting. Your app sets it right after opening a transaction.

-- inside the same transaction as the request

SELECT set_config('app.current_tenant', '22222222-2222-2222-2222-222222222222', true);

Enable RLS and start with read access.

ALTER TABLE projects ENABLE ROW LEVEL SECURITY;

CREATE POLICY projects_tenant_select

ON projects

FOR SELECT

TO app_user

USING (tenant_id = current_setting('app.current_tenant')::uuid);

Prove it works by trying two different tenants and checking that the row count changes.

Read policies don’t protect writes. Add WITH CHECK so inserts and updates can’t smuggle rows into the wrong tenant.

CREATE POLICY projects_tenant_write

ON projects

FOR INSERT, UPDATE

TO app_user

WITH CHECK (tenant_id = current_setting('app.current_tenant')::uuid);

A quick way to verify behavior (including failures) is to keep a tiny SQL script you can re-run after every migration:

BEGIN; SET LOCAL ROLE app_user;SELECT set_config('app.current_tenant', '<tenant A>', true); SELECT count(*) FROM projects;INSERT INTO projects(id, tenant_id, name) VALUES (gen_random_uuid(), '<tenant B>', 'bad'); (should fail)UPDATE projects SET tenant_id = '<tenant B>' WHERE ...; (should fail)ROLLBACK;If you can run that script and get the same results every time, you have a reliable baseline before expanding RLS to other tables.

Most teams adopt RLS after getting tired of repeating the same authorization checks in every query. The good news is that the policy shapes you need are usually consistent.

Some tables are naturally owned by one user (notes, API tokens). Others belong to a tenant where access depends on membership. Treat these as different patterns.

For owner-only data, policies often check created_by = app_user_id(). For tenant data, policies often check whether the user has a membership row for the org.

A practical way to keep policies readable is to centralize identity in small SQL helpers and reuse them:

-- Example helpers

create function app_user_id() returns uuid

language sql stable as $$

select current_setting('app.user_id', true)::uuid

$$;

create function app_is_admin() returns boolean

language sql stable as $$

select current_setting('app.is_admin', true) = 'true'

$$;

Reads are often broader than writes. For example, any org member can SELECT projects, but only editors can UPDATE, and only owners can DELETE.

Keep it explicit: one policy for SELECT (membership), one policy for INSERT/UPDATE with WITH CHECK (role), and one for DELETE (often stricter than update).

Avoid “turn RLS off for admins.” Instead, add an escape hatch inside policies, like app_is_admin(), so you don’t accidentally grant full access to a shared service role.

If you use deleted_at or status, bake it into the SELECT policy (deleted_at is null). Otherwise, someone can “resurrect” rows by flipping flags the app assumed were final.

WITH CHECK friendlyINSERT ... ON CONFLICT DO UPDATE must satisfy WITH CHECK for the row after the write. If your policy requires created_by = app_user_id(), make sure your upsert sets created_by on insert and doesn’t overwrite it on update.

If you generate backend code, these patterns are worth turning into internal templates so new tables start with safe defaults instead of a blank slate.

RLS is great until one small detail makes it look like PostgreSQL is “randomly” hiding or showing data. The mistakes below waste the most time.

The first trap is forgetting WITH CHECK on insert and update. USING controls what you can see, not what you’re allowed to create or change. Without WITH CHECK, an app bug can write a row into the wrong tenant, and you might not notice because that same user can’t read it back.

Another common leak is the “leaky join.” You correctly filter projects, then join to invoices, notes, or files that aren’t protected the same way. The fix is strict but straightforward: every table that can reveal tenant data needs its own policy, and views should not depend on only one table being safe.

Common failure patterns show up early:

WITH CHECK.Policies that reference the same table (directly or through a view) can create recursion surprises. A policy might check membership by querying a view that reads the protected table again, leading to errors, slow queries, or a policy that never matches.

Role setup is another source of confusion. Table owners and elevated roles can bypass RLS, so your tests pass while real users fail (or the other way around). Always test with the same low-privilege role your app uses.

Be cautious with SECURITY DEFINER functions. They run with the function owner’s privileges, so a helper like current_tenant_id() can be fine, but a “convenience” function that reads data can accidentally read across tenants unless you design it to respect RLS.

Also set a safe search_path inside security definer functions. If you don’t, the function can pick up a different object with the same name, and your policy logic can quietly point at the wrong thing depending on session state.

RLS bugs are usually missing context, not “bad SQL.” A policy can be correct on paper and still fail because the session role is different than you think, or because the request never set the tenant and user values your policy relies on.

A reliable way to reproduce a production report is to mirror the same session setup locally and run the exact query. That usually means:

SET ROLE app_user; (or the real API role)SELECT set_config('app.tenant_id', 't_123', true); and SELECT set_config('app.user_id', 'u_456', true);SELECT current_user, current_setting('app.tenant_id', true), current_setting('app.user_id', true);When you’re unsure which policy is applied, check the catalog instead of guessing. pg_policies shows each policy, the command, and the USING and WITH CHECK expressions. Pair that with pg_class to confirm RLS is enabled on the table and not bypassed.

Performance issues can look like auth issues. A policy that joins a membership table or calls a function might be correct but slow once the table grows. Use EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS) on the reproduced query and look for sequential scans, unexpected nested loops, or filters applied late. Missing indexes on (tenant_id, user_id) and membership tables are common causes.

It also helps to log three values per request at the app layer: the tenant ID, the user ID, and the database role used for the request. When those don’t match what you think you set, RLS will behave “wrong” because the inputs are wrong.

For tests, keep a few seed tenants and make failures explicit. A small suite usually includes: “Tenant A cannot read Tenant B,” “user without membership cannot see the project,” “owner can update, viewer cannot,” “insert is blocked unless tenant_id matches context,” and “admin override only applies where intended.”

Treat RLS like a seatbelt, not a feature toggle. Small misses turn into “everyone can see everyone’s data” or “everything returns zero rows.”

Make sure your table design and policy rules match your tenant model.

tenant_id). If it doesn’t, write down why (for example, global reference tables).FORCE ROW LEVEL SECURITY on those tables.USING. Writes must have WITH CHECK so inserts and updates can’t move a row into another tenant.tenant_id or join through membership tables, add the matching indexes.A simple sanity scenario: a tenant A user can read their own invoices, can insert an invoice only for tenant A, and cannot update an invoice to change tenant_id.

RLS is only as strong as the roles your app uses.

bypassrls.Picture a B2B app where companies (orgs) have projects, and projects have tasks. Users can belong to multiple orgs, and a user may be a member of some projects but not others. This is a good fit for RLS because the database can enforce tenant isolation even if an API endpoint forgets a filter.

A simple model is: orgs, users, org_memberships (org_id, user_id, role), projects (id, org_id), project_memberships (project_id, user_id), tasks (id, project_id, org_id, ...). That org_id on tasks is intentional. It keeps policies simple and reduces surprises during joins.

A classic leak happens when tasks only have project_id, and your policy checks access through a join to projects. One mistake (a permissive policy on projects, a join that drops a condition, or a view that changes context) can expose tasks from another org.

A safer migration path avoids breaking production traffic:

org_id to tasks, add membership tables).tasks.org_id from projects.org_id, then add NOT NULL.Support access is usually best handled with a narrow break-glass role, not by disabling RLS. Keep it separate from normal support accounts and make it explicit when it’s used.

Document the rules so policies don’t drift: which session variables must be set (user_id, org_id), which tables must carry org_id, what “member” means, and a few SQL examples that should return 0 rows when run as the wrong org.

RLS is easiest to live with when you treat it like a product change. Roll it out in small chunks, prove behavior with tests, and keep a clear record of why each policy exists.

A rollout plan that tends to work:

projects) and lock it down.After the first table is stable, make policy changes deliberate. Add a policy review step to migrations, and include a short note on intent (who should access what and why) plus a matching test update. This prevents “just add another OR” policies that slowly turn into a hole.

If you’re moving quickly, tools like Koder.ai (koder.ai) can help you generate a Go + PostgreSQL starting point via chat, and then you can layer RLS policies and tests on top with the same discipline as a hand-built backend.

Finally, keep safety rails during rollout. Take snapshots before policy migrations, practice rollback until it’s boring, and keep a small break-glass path for support that doesn’t disable RLS across the whole system.

RLS makes PostgreSQL enforce which rows are visible or writable for a request, so tenant isolation doesn’t depend on every endpoint remembering the right WHERE tenant_id = ... filter. The main win is reducing “one missed check” bugs when your app grows and queries multiply.

It’s worth it when access rules are consistent and row-based, like tenant isolation or membership-based access, and you have many query paths (search, exports, admin screens, background jobs). It’s usually not worth it if most rules are per-field, highly exception-driven, or dominated by wide reporting that needs cross-tenant reads.

Use RLS for row visibility and basic write gating, then use other tools for the rest. Column privacy typically needs views and column privileges, and complex business rules (like billing ownership or approval flows) still belong in application logic or carefully designed database constraints.

Create a low-privilege role for the API (not the table owner), enable RLS, then add a SELECT policy and an INSERT/UPDATE policy with WITH CHECK. Set a request-scoped session value (like app.current_tenant) and verify that switching it changes which rows you can see and write.

A common default is a session variable per request, set at the start of the transaction, such as app.tenant_id and app.user_id. The key is consistency: every code path (web requests, jobs, scripts) must set the same values the policies expect, or you’ll get confusing “zero rows” behavior.

USING controls which existing rows are visible and targetable for SELECT, UPDATE, and DELETE. WITH CHECK controls which new or changed rows are allowed during INSERT and UPDATE, so it prevents “writing into another tenant” even if the app passes a bad .

If you only add USING, a buggy endpoint can still insert or update rows into the wrong tenant, and you might not notice because the same user can’t read the bad row back. Always pair tenant read rules with a matching WITH CHECK rule for writes so bad data can’t be created in the first place.

Avoid joins inside policies by putting the tenant key (like org_id) directly on tenant-owned tables, even if they also reference another table that has it. Add explicit membership tables (org_memberships, optionally project_memberships) so policies can do one indexed lookup instead of complicated inference.

First, reproduce the same session context your app uses by setting the same role and session settings, then run the exact SQL query. Next, confirm RLS is enabled and inspect pg_policies to see which USING and WITH CHECK expressions are applied, because RLS often fails by missing identity context rather than “bad SQL.”

Yes, but treat generated code as a starting point, not a security system. If you use Koder.ai to generate a Go + PostgreSQL backend, you still need to define your tenant model, set session identity consistently, and add policies and tests deliberately so new tables don’t ship without the right protections.

tenant_id