Aug 22, 2025·8 min

Postgres transactions for multi-step workflows: practical patterns

Learn Postgres transactions for multi-step workflows: how to group updates safely, prevent partial writes, handle retries, and keep data consistent.

Why multi-step updates often end up inconsistent

Most real features are not one database update. They are a short chain: insert a row, update a balance, mark a status, write an audit record, maybe enqueue a job. A partial write happens when only some of those steps make it to the database.

This shows up when something interrupts the chain: a server error, a timeout between your app and Postgres, a crash after step 2, or a retry that re-runs step 1. Each statement is fine on its own. The workflow breaks when it stops mid-way.

You can usually spot it quickly:

- A row exists, but a related row is missing (order created, no items)

- Money moved, but the status did not change (paid, still marked unpaid)

- Two records that should be one (duplicate subscriptions after a retry)

- Flags that disagree (user is "active" but has no plan)

- States that only appear under load or failures

A concrete example: a plan upgrade updates the customer’s plan, adds a payment record, and increases available credits. If the app crashes after saving the payment but before adding credits, support sees "paid" in one table and "no credits" in another. If the client retries, you might even record the payment twice.

The goal is simple: treat the workflow like a single switch. Either every step succeeds, or none of them do, so you never store half-finished work.

Transactions, in plain terms

A transaction is the database’s way of saying: treat these steps as one unit of work. Either every change happens, or none of them do. This matters any time your workflow needs more than one update, like creating a row, updating a balance, and writing an audit record.

Think of moving money between two accounts. You must subtract from Account A and add to Account B. If the app crashes after the first step, you do not want the system to "remember" only the subtraction.

Commit vs rollback

When you commit, you tell Postgres: keep everything I did in this transaction. All changes become permanent and visible to other sessions.

When you rollback, you tell Postgres: forget everything I did in this transaction. Postgres undoes the changes as if the transaction never happened.

What Postgres guarantees (and what it doesn’t)

Inside a transaction, Postgres guarantees you won’t expose half-finished results to other sessions before you commit. If something fails and you roll back, the database cleans up the writes from that transaction.

A transaction does not fix bad workflow design. If you subtract the wrong amount, use the wrong user ID, or skip a needed check, Postgres will faithfully commit the wrong result. Transactions also do not automatically prevent every business-level conflict (like overselling inventory) unless you pair them with the right constraints, locks, or isolation level.

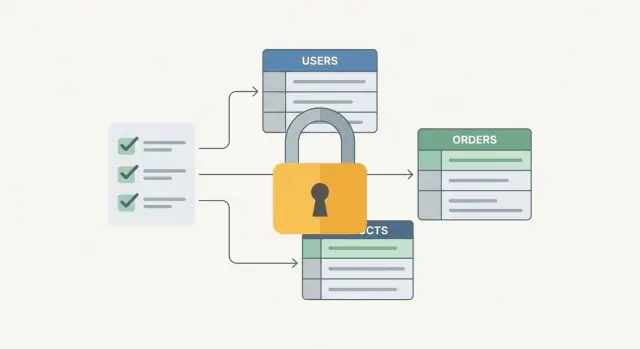

Workflows that should be grouped

Any time you update more than one table (or more than one row) to finish a single real-world action, you have a candidate for a transaction. The point stays the same: either everything is done, or nothing is.

An order flow is the classic case. You might create an order row, reserve inventory, take a payment, then mark the order as paid. If payment succeeds but the status update fails, you have money captured with an order that still looks unpaid. If the order row is created but stock is not reserved, you can sell items you do not actually have.

User onboarding quietly breaks in the same way. Creating the user, inserting a profile record, assigning roles, and recording that a welcome email should be sent are one logical action. Without grouping, you can end up with a user who can sign in but has no permissions, or a profile that exists with no user.

Back-office actions often need strict "paper trail + state change" behavior. Approving a request, writing an audit entry, and updating a balance should succeed together. If the balance changes but the audit log is missing, you lose evidence of who changed what and why.

Background jobs benefit too, especially when you process a work item with multiple steps: claim the item so two workers don’t do it, apply the business update, record a result for reporting and retries, then mark the item done (or failed with a reason). If those steps drift apart, retries and concurrency create a mess.

Design the workflow before you write SQL

Multi-step features break when you treat them like a pile of independent updates. Before you open a database client, write the workflow as a short story with one clear finish line: what exactly counts as "done" for the user?

Start by listing the steps in plain language, then define a single success condition. For example: "Order is created, inventory is reserved, and the user sees an order confirmation number." Anything short of that is not success, even if some tables were updated.

Next, draw a hard line between database work and external work. Database steps are the ones you can protect with transactions. External calls like card payments, sending emails, or calling third-party APIs can fail in slow, unpredictable ways, and you usually cannot roll them back.

A simple planning approach: separate steps into (1) must be all-or-nothing, (2) can happen after commit.

Decide what belongs inside the transaction

Inside the transaction, keep only the steps that must remain consistent together:

- Create or update core rows (order, invoice, account balance)

- Reserve shared resources (inventory, seats, quota)

- Record a durable "what to do next" event (outbox table)

- Enforce rules with constraints (unique keys, foreign keys)

Move side effects outside. For example, commit the order first, then send the confirmation email based on an outbox record.

Write rollback expectations per step

For each step, write what should happen if the next step fails. "Rollback" might mean a database rollback, or it might mean a compensating action.

Example: if payment succeeds but inventory reservation fails, decide up front whether you refund immediately, or mark the order as "payment captured, awaiting stock" and handle it asynchronously.

Step-by-step: wrapping a workflow in a transaction

A transaction tells Postgres: treat these steps as one unit. Either all of them happen, or none of them do. That’s the simplest way to prevent partial writes.

The basic flow

Use one database connection (one session) from start to finish. If you spread steps across different connections, Postgres cannot guarantee the all-or-nothing result.

The sequence is straightforward: begin, run the required reads and writes, commit if everything succeeds, otherwise roll back and return a clear error.

Here’s a minimal example in SQL:

BEGIN;

-- reads that inform your decision

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 42 FOR UPDATE;

-- writes that must stay together

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 50 WHERE id = 42;

INSERT INTO ledger(account_id, amount, note) VALUES (42, -50, 'Purchase');

COMMIT;

-- on error (in code), run:

-- ROLLBACK;

Keep it short (and debuggable)

Transactions hold locks while they run. The longer you keep them open, the more you block other work and the more likely you are to hit timeouts or deadlocks. Do the essentials inside the transaction, and move slow tasks (sending emails, calling payment providers, generating PDFs) outside.

When something fails, log enough context to reproduce the problem without leaking sensitive data: workflow name, order_id or user_id, key parameters (amount, currency), and the Postgres error code. Avoid logging full payloads, card data, or personal details.

Concurrency basics: locks and isolation without the jargon

Make retries non-destructive

Create a Postgres-backed app that uses idempotency keys to make retries safe.

Concurrency is just two things happening at the same time. Picture two customers trying to buy the last concert ticket. Both screens show "1 left," both click Pay, and now your app has to decide who gets it.

Without protection, both requests can read the same old value and both write an update. That’s how you end up with negative inventory, duplicated reservations, or a payment with no order.

Row locks are the simplest guardrail. You lock the specific row you are about to change, do your checks, then update it. Other transactions that touch the same row must wait until you commit or roll back, which prevents double updates.

A common pattern: start a transaction, select the inventory row with FOR UPDATE, verify there is stock, decrement it, then insert the order. That "holds the door" while you finish the critical steps.

Isolation levels control how much overlap weirdness you allow from concurrent transactions. The trade-off is usually safety vs speed:

- Read Committed (default): fast, but you can see changes committed by others between statements.

- Repeatable Read: your transaction sees a stable snapshot, good for consistent reads, may cause more retries.

- Serializable: strongest safety, Postgres may abort one transaction to keep results as if they ran one-by-one.

Keep locks short. If a transaction sits open while you call an external API or wait for a user action, you will create long waits and timeouts. Prefer a clear failure path: set a lock timeout, catch the error, and return "please retry" instead of letting requests hang.

If you need to do work outside the database (like charging a card), split the workflow: reserve quickly, commit, then do the slow part, and finalize with another short transaction.

Retries that do not create duplicates

Retries are normal in Postgres-backed apps. A request can fail even when your code is correct: deadlocks, statement timeouts, brief network drops, or a serialization error under higher isolation levels. If you just rerun the same handler, you risk creating a second order, charging twice, or inserting duplicate "event" rows.

The fix is idempotency: the operation should be safe to run twice with the same input. The database should be able to recognize "this is the same request" and respond consistently.

A practical pattern is to attach an idempotency key (often a client-generated request_id) to every multi-step workflow and store it on the main record, then add a unique constraint on that key.

For example: in checkout, generate request_id when the user clicks Pay, then insert the order with that request_id. If a retry happens, the second attempt hits the unique constraint and you return the existing order instead of creating a new one.

What usually matters:

- Use a unique constraint on (request_id) or (user_id, request_id) to block duplicates.

- When the constraint is hit, fetch the existing row and return the same result.

- Make side effects follow the same rule: only one payment intent per order, only one "order confirmed" event per order.

- Log the request_id so support can trace what happened.

Keep the retry loop outside the transaction. Each attempt should start a fresh transaction and rerun the whole unit of work from the top. Retrying inside a failed transaction does not help because Postgres marks it as aborted.

One small example: your app tries to create an order and reserve inventory, but it times out right after COMMIT. The client retries. With an idempotency key, the second request returns the already-created order and skips a second reservation instead of doubling the work.

Use the database to enforce rules, not just your code

Keep full control

Get source code you can review, customize, and audit for transaction safety.

Transactions keep a multi-step workflow together, but they do not automatically make the data correct. A strong way to avoid partial-write fallout is to make "wrong" states hard or impossible in the database, even if a bug slips into application code.

Start with basic safety rails. Foreign keys make sure references are real (an order line cannot point to a missing order). NOT NULL stops half-filled rows. CHECK constraints catch values that do not make sense (for example, quantity > 0, total_cents >= 0). These rules run on every write, no matter which service or script touches the database.

For longer workflows, model state changes explicitly. Instead of many boolean flags, use one status column (pending, paid, shipped, canceled) and only allow valid transitions. You can enforce this with constraints or triggers so the database refuses illegal jumps like shipped -> pending.

Uniqueness is another form of correctness. Add unique constraints where duplicates would break your workflow: order_number, invoice_number, or an idempotency_key used for retries. Then, if your app retries the same request, Postgres blocks the second insert and you can safely return "already processed" instead of creating a second order.

When you need traceability, store it explicitly. An audit table (or history table) that records who changed what, and when, turns "mystery updates" into facts you can query during incidents.

Common mistakes that cause partial writes

Most partial writes are not caused by "bad SQL." They come from workflow decisions that make it easy to commit only half the story.

The traps that show up in real apps

- Doing slow external work while the transaction is open. Calling a payment provider, sending email, or uploading a file inside the transaction keeps locks held longer than needed. If the API is slow or times out, other users queue up behind your open transaction.

- Reading outside the transaction, then writing later. Example: you fetch a user’s balance, show it on screen, then later deduct based on that old value. Another session may have changed the balance in between.

- Catching an error but still committing something. A common pattern is "try step 1, try step 2, log the error, return success anyway." If the code reaches COMMIT after a failure, you just made the database inconsistent on purpose.

- Updating tables in different orders across code paths. If one request updates

accountsthenorders, but another updatesordersthenaccounts, you increase the chance of deadlocks under load. - Keeping transactions open too long. Long transactions can block writes, delay vacuum cleanup, and create confusing timeouts.

A concrete example: in checkout, you reserve inventory, create an order, and then charge a card. If you charge the card inside the same transaction, you might hold an inventory lock while waiting on the network. If the charge succeeds but your transaction later rolls back, you charged the customer without an order.

A safer pattern is: keep the transaction focused on database state (reserve inventory, create order, record payment pending), commit, then call the external API, then write back the result in a new short transaction. Many teams implement this with a simple pending status and a background job.

Quick checklist for all-or-nothing operations

When a workflow has multiple steps (insert, update, charge, send), the goal is simple: either everything is recorded, or nothing is.

Transaction boundaries

Keep every required database write inside one transaction. If one step fails, roll back and leave the data exactly as it was.

Make the success condition explicit. For example: "Order is created, stock is reserved, and payment status is recorded." Anything else is a failure path that must abort the transaction.

- All required writes happen inside a single

BEGIN ... COMMITblock. - There is one clear done state in the database (not just in app memory).

- Any error leads to

ROLLBACK, and the caller gets a clear failure result.

Safety rails (so retries do not hurt)

Assume the same request may be retried. The database should help you enforce only-once rules.

- Back only-once actions with unique constraints (one payment record per order, or one reservation per item per order).

- Make retries safe and repeatable (same input produces the same final state, not duplicates).

Keep transactions short

Do the minimum work inside the transaction, and avoid waiting on network calls while holding locks.

- Keep transactions short, and set a timeout so they do not hang.

- Do slow work (like calling a payment provider) outside the transaction, then record the result in a new short transaction.

Observe failures

If you can’t see where it breaks, you will keep guessing.

- Log the workflow step and a request id for every failure.

- Monitor rollback rates and lock timeouts so you catch partial-write risks early.

Example: a checkout flow that stays consistent under failure

Test failure cases safely

Experiment with transactions and rollbacks confidently with snapshots while you iterate.

A checkout has several steps that should move together: create the order, reserve inventory, record the payment attempt, then mark the order status.

Imagine a user clicks Buy for 1 item.

A safe flow (DB work is one unit)

Inside one transaction, do only database changes:

- Insert an

ordersrow with statuspending_payment. - Reserve stock (for example, decrement

inventory.availableor create areservationsrow). - Insert a

payment_intentsrow with a client-providedidempotency_key(unique). - Insert an

outboxrow like "order_created".

If any statement fails (out of stock, constraint error, crash), Postgres rolls back the whole transaction. You do not end up with an order but no reservation, or a reservation with no order.

What if payment fails halfway through?

The payment provider is outside your database, so treat it as a separate step.

If the provider call fails before you commit, abort the transaction and nothing is written. If the provider call fails after you commit, run a new transaction that marks the payment attempt as failed, releases the reservation, and sets the order status to canceled.

Retry without creating a second order

Have the client send an idempotency_key per checkout attempt. Enforce it with a unique index on payment_intents(idempotency_key) (or on orders if you prefer). On retry, your code looks up the existing rows and continues instead of inserting a new order.

Emails and notifications

Do not send emails inside the transaction. Write an outbox record in the same transaction, then let a background worker send the email after commit. That way you never email for an order that got rolled back.

Next steps: apply this to one workflow this week

Pick one workflow that touches more than one table: signup + welcome email enqueue, checkout + inventory, invoice + ledger entry, or create project + default settings.

Write the steps first, then write the rules that must always be true (your invariants). Example: "An order is either fully paid and reserved, or not paid and not reserved. Never half-reserved." Turn those rules into an all-or-nothing unit.

A simple plan:

- List the exact SQL operations in order (reads, inserts, updates, deletes).

- Add the missing database constraints first (unique keys, foreign keys, check constraints).

- Add an idempotency key for the request so retries do not create duplicates.

- Wrap the steps in one transaction and make the success point explicit (commit only when all checks pass).

- Decide what a safe retry looks like (same idempotency key, same outcome).

Then test the ugly cases on purpose. Simulate a crash after step 2, a timeout right before commit, and a double-submit from the UI. The goal is boring outcomes: no orphan rows, no double charges, no pending forever.

If you’re prototyping quickly, it helps to sketch the workflow in a planning-first tool before you generate handlers and schema. For example, Koder.ai (koder.ai) has a Planning Mode and supports snapshots and rollback, which can be handy while you iterate on transaction boundaries and constraints.

Do this for one workflow this week. The second one will be much faster.