Dec 28, 2025·7 min

Object storage vs database blobs for fast, cheap uploads

Object storage vs database blobs: model file metadata in Postgres, store bytes in object storage, and keep downloads fast with predictable costs.

Object storage vs database blobs: model file metadata in Postgres, store bytes in object storage, and keep downloads fast with predictable costs.

User uploads sound simple: accept a file, save it, show it later. That works with a few users and small files. Then volume grows, files get larger, and the pain shows up in places that have nothing to do with the upload button.

Downloads slow down because your app server or database is doing the heavy lifting. Backups become huge and slow, so restores take longer right when you need them. Storage bills and bandwidth (egress) bills can spike because files are served inefficiently, duplicated, or never cleaned up.

What you usually want is boring and reliable: fast transfers under load, clear access rules, simple operations (backup, restore, cleanup), and costs that stay predictable as usage grows.

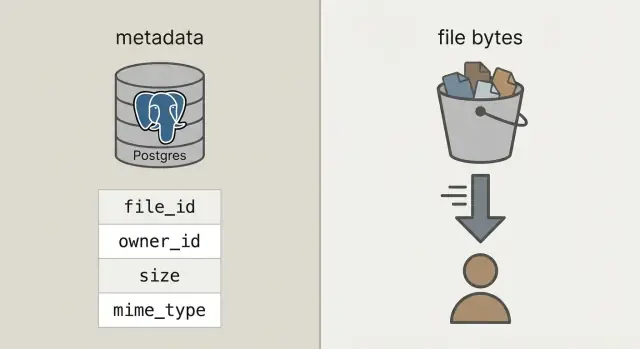

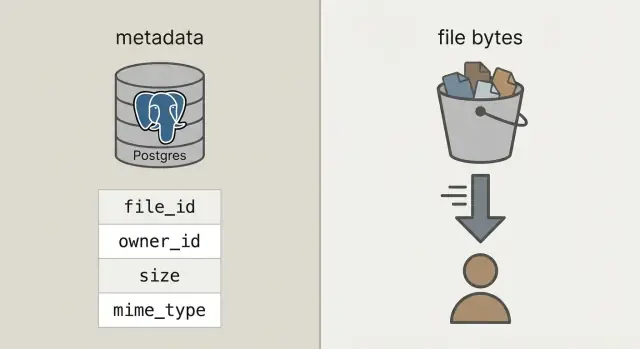

To get there, separate two things that often get mixed together:

Metadata is small information about a file: who owns it, what it's called, size, type, when it was uploaded, and where it lives. This belongs in your database (like Postgres) because you need to query it, filter it, and join it to users, projects, and permissions.

File bytes are the actual contents of the file (the photo, PDF, video). Storing bytes inside database blobs can work, but it makes databases heavier, backups larger, and performance harder to predict. Putting bytes in object storage keeps the database focused on what it does best, while files are served quickly and cheaply by systems built for that job.

When people say "store uploads in the database," they usually mean database blobs: either a BYTEA column (raw bytes in a row) or Postgres "large objects" (a feature that stores big values separately). Both can work, but both make your database responsible for serving file bytes.

Object storage is a different idea: the file lives in a bucket as an object, addressed by a key (like uploads/2026/01/file.pdf). It's built for big files, cheap storage, and streaming downloads. It also handles many concurrent reads well, without tying up your database connections.

Postgres shines at queries, constraints, and transactions. It's great for metadata like who owns the file, what it is, when it was uploaded, and whether it can be downloaded. That metadata is small, easy to index, and easy to keep consistent.

A practical rule of thumb:

A quick sanity check: if backups, replicas, and migrations would become painful with file bytes included, keep the bytes out of Postgres.

The setup most teams end up with is straightforward: store bytes in object storage, and store the file record (who owns it, what it is, where it lives) in Postgres. Your API coordinates and authorizes, but it doesn't proxy large uploads and downloads.

That gives you three clear responsibilities:

file_id, owner, size, content type, and the object pointer.That stable file_id becomes the primary key for everything: comments that reference an attachment, invoices that point to a PDF, audit logs, and support tools. Users may rename a file, you may move it between buckets, and the file_id stays the same.

When possible, treat stored objects as immutable. If a user replaces a document, create a new object (and usually a new row or a new version row) instead of overwriting bytes in place. It simplifies caching, avoids "old link returns new file" surprises, and gives you a clean rollback story.

Decide privacy early: private by default, public only by exception. A good rule is: the database is the source of truth for who can access a file; object storage enforces whatever short-lived permission your API grants.

With the clean split, Postgres stores facts about the file, and object storage stores the bytes. That keeps your database smaller, backups faster, and queries simple.

A practical uploads table only needs a few fields to answer real questions like "who owns this?", "where is it stored?", and "is it safe to download?"

CREATE TABLE uploads (

id uuid PRIMARY KEY,

owner_id uuid NOT NULL,

bucket text NOT NULL,

object_key text NOT NULL,

size_bytes bigint NOT NULL,

content_type text,

original_filename text,

checksum text,

state text NOT NULL CHECK (state IN ('pending','uploaded','failed','deleted')),

created_at timestamptz NOT NULL DEFAULT now()

);

CREATE INDEX uploads_owner_created_idx ON uploads (owner_id, created_at DESC);

CREATE INDEX uploads_checksum_idx ON uploads (checksum);

A few decisions that save pain later:

bucket + object_key as the storage pointer. Keep it immutable once uploaded.pending row. Flip to uploaded only after your system confirms the object exists and the size (and ideally checksum) matches.original_filename for display only. Don't trust it for type or security decisions.If you support replacements (like a user re-uploading an invoice), add a separate upload_versions table with upload_id, version, object_key, and created_at. That way you can keep history, roll back mistakes, and avoid breaking old references.

Keep uploads fast by making your API handle coordination, not the file bytes. Your database stays responsive, while object storage takes the bandwidth hit.

Start by creating an upload record before anything is sent. Your API returns an upload_id, where the file will live (an object_key), and a short-lived upload permission.

A common flow:

pending, plus expected size and intended content type.upload_id and any storage response fields (like ETag). Your server verifies size, checksum (if you use one), and content type, then marks the row uploaded.failed and optionally delete the object.Retries and duplicates are normal. Make the finalize call idempotent: if the same upload_id is finalized twice, return success without changing anything.

To reduce duplicates across retries and re-uploads, store a checksum and treat "same owner + same checksum + same size" as the same file.

A good download flow starts with one stable URL in your app, even if the bytes live somewhere else. Think: /files/{file_id}. Your API uses file_id to look up metadata in Postgres, checks permission, then decides how to deliver the file.

file_id.uploaded.Redirects are simple and fast for public or semi-public files. For private files, presigned GET URLs keep storage private while still letting the browser download directly.

For video and large downloads, make sure your object storage (and any proxy layer) supports range requests (Range headers). This enables seeking and resumable downloads. If you funnel bytes through your API, range support often breaks or becomes expensive.

Caching is where speed comes from. Your stable /files/{file_id} endpoint should usually be non-cacheable (it's an auth gate), while the object storage response can often be cached based on content. If files are immutable (new upload = new key), you can set a long cache lifetime. If you overwrite files, keep cache times short or use versioned keys.

A CDN helps when you have lots of global users or big files. If your audience is small or mostly in one region, object storage alone is often enough and cheaper to start with.

Surprise bills usually come from downloads and churn, not the raw bytes sitting on disk.

Price the four drivers that move the needle: how much you store, how often you read and write (requests), how much data leaves your provider (egress), and whether you use a CDN to reduce repeated origin downloads. A small file downloaded 10,000 times can cost more than a large file nobody touches.

Controls that keep spend steady:

Lifecycle rules are often the easiest win. For example: keep original photos "hot" for 30 days, then move them to a cheaper storage class; keep invoices for 7 years, but delete failed upload parts after 7 days. Even basic retention policies stop storage creep.

Deduplication can be simple: store a content hash (like SHA-256) in your file metadata table and enforce uniqueness per owner. When a user uploads the same PDF twice, you can reuse the existing object and just create a new metadata row.

Finally, track usage where you already do user accounting: Postgres. Store bytes_uploaded, bytes_downloaded, object_count, and last_activity_at per user or workspace. That makes it easy to show limits in the UI and trigger alerts before you get the bill.

Security for uploads comes down to two things: who can access a file, and what you can prove later if something goes wrong.

Start with a clear access model and encode it in Postgres metadata, not in one-off rules scattered across services.

A simple model that covers most apps:

For private files, avoid exposing raw object keys. Issue time-limited, scope-limited presigned upload and download URLs, and rotate them often.

Verify encryption both in transit and at rest. In transit means HTTPS end to end, including uploads directly to storage. At rest means server-side encryption in your storage provider, and that backups and replicas are also encrypted.

Add checkpoints for safety and data quality: validate content type and size before issuing an upload URL, then validate again after upload (based on actual stored bytes, not just the filename). If your risk profile needs it, run malware scanning asynchronously and quarantine the file until it passes.

Store audit fields so you can investigate incidents and meet basic compliance needs: uploaded_by, ip, user_agent, and last_accessed_at are a practical baseline.

If you have data residency requirements, pick the storage region deliberately and keep it consistent with where you run compute.

Most upload problems aren't about raw speed. They come from design choices that feel convenient early on, then get painful when you have real traffic, real data, and real support tickets.

A concrete example: if a user replaces a profile photo three times, you can end up paying for three old objects forever unless you schedule cleanup. A safe pattern is a soft delete in Postgres, then a background job that removes the object and records the result.

Most problems show up when the first big file arrives, a user refreshes mid-upload, or someone deletes an account and the bytes stay behind.

Make sure your Postgres table records the file's size, checksum (so you can verify integrity), and a clear state path (for example: pending, uploaded, failed, deleted).

A last-mile checklist:

One concrete test: upload a 2 GB file, refresh the page at 30%, then resume. Then download it on a slow connection and seek to the middle. If either flow is shaky, fix it now, not after launch.

A simple SaaS app often has two very different upload types: profile photos (frequent, small, safe to cache) and PDF invoices (sensitive, must stay private). This is where the split between metadata in Postgres and bytes in object storage pays off.

Here's what the metadata can look like in one files table, with a couple fields that matter for behavior:

| field | profile photo example | invoice PDF example |

|---|---|---|

kind | avatar | invoice_pdf |

visibility | private (served via signed URL) | private |

cache_control | public, max-age=31536000, immutable | no-store |

object_key | users/42/avatars/2026-01-17T120102Z.webp | orgs/7/invoices/INV-1049.pdf |

status | uploaded | uploaded |

size_bytes | 184233 | 982341 |

When a user replaces a photo, treat it as a new file, not an overwrite. Create a new row and new object_key, then update the user profile to point to the new file ID. Mark the old row as replaced_by=<new_id> (or deleted_at), and delete the old object later with a background job. This keeps history, makes rollbacks easier, and avoids race conditions.

Support and debugging get easier because the metadata tells a story. When someone says "my upload failed," support can check status, a human-readable last_error, a storage_request_id or etag (to trace storage logs), timestamps (did it stall?), and the owner_id and kind (is the access policy correct?).

Start small and make the happy path boring: files upload, metadata saves, downloads are fast, and nothing gets lost.

A good first milestone is a minimal Postgres table for file metadata plus a single upload flow and a single download flow you can explain on a whiteboard. Once that works end to end, add versions, quotas, and lifecycle rules.

Pick one clear storage policy per file type and write it down. For example, profile photos might be cacheable, while invoices should be private and only accessible via short-lived download URLs. Mixing policies inside one bucket prefix without a plan is how accidental exposure happens.

Add instrumentation early. The numbers you want from day one are upload finalize failure rate, orphan rate (objects without a matching DB row, and vice versa), egress volume by file type, P95 download latency, and average object size.

If you want a faster way to prototype this pattern, Koder.ai (koder.ai) is built around generating full apps from chat, and it matches the common stack used here (React, Go, Postgres). It can be a handy way to iterate on the schema, endpoints, and background cleanup jobs without rewriting the same scaffolding over and over.

After that, add only what you can explain in one sentence: "we keep old versions for 30 days" or "each workspace gets 10 GB." Keep it simple until real usage forces your hand.

Use Postgres for metadata you need to query and secure (owner, permissions, state, checksum, pointer). Put the bytes in object storage so downloads and large transfers don’t consume database connections or inflate backups.

It makes your database do double duty as a file server. That increases table size, slows backups and restores, adds replication load, and can make performance less predictable when many users download at once.

Yes. Keep one stable file_id in your app, store metadata in Postgres, and store bytes in object storage addressed by bucket and object_key. Your API should authorize access and hand out short-lived upload/download permissions instead of proxying the bytes.

Create a pending row first, generate a unique object_key, then let the client upload directly to storage using a short-lived permission. After upload, have the client call a finalize endpoint so your server can verify size and checksum (if you use one) before marking the row as uploaded.

Because real uploads fail and retry. A state field lets you distinguish files that are expected but not present (pending), completed (uploaded), broken (failed), and removed (deleted) so your UI, cleanup jobs, and support tools behave correctly.

Treat original_filename as display-only. Generate a unique storage key (often a UUID-based path) to avoid collisions, strange characters, and security surprises. You can still show the original name in the UI while keeping storage paths clean and predictable.

Use a stable app URL like /files/{file_id} as the permission gate. After checking access in Postgres, return a redirect or a short-lived signed download permission so the client downloads from object storage directly, keeping your API out of the hot path.

Egress and repeated downloads usually dominate, not raw storage. Set file size limits and quotas, use retention/lifecycle rules, deduplicate by checksum where it makes sense, and track usage counters so you can alert before bills spike.

Store permissions and visibility in Postgres as the source of truth, and keep storage private by default. Validate type and size before and after upload, use HTTPS end-to-end, encrypt at rest, and add audit fields so you can investigate issues later.

Start with one metadata table, one direct-to-storage upload flow, and one download gate endpoint, then add cleanup jobs for orphaned objects and soft-deleted rows. If you want to prototype quickly on a React/Go/Postgres stack, Koder.ai can generate the endpoints, schema, and background tasks from chat and let you iterate without rewriting boilerplate.