May 06, 2025·8 min

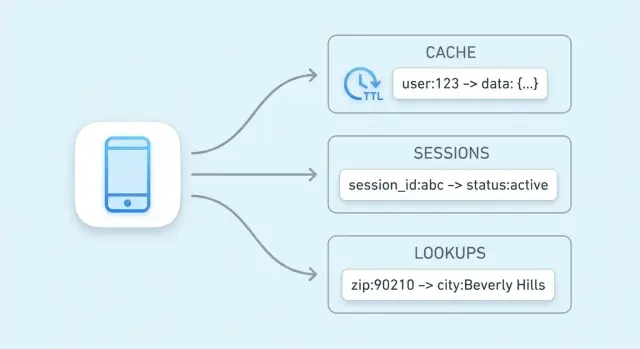

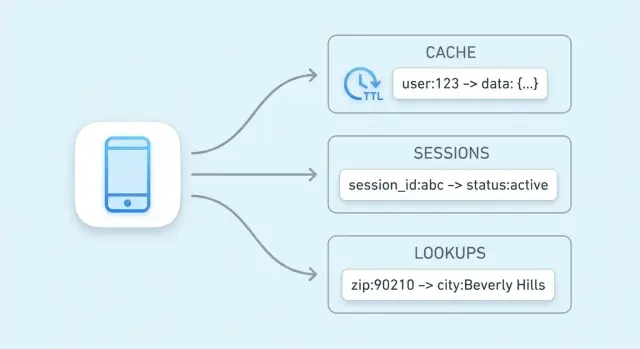

Key-Value Stores for Caching, Sessions, and Fast Lookups

Learn how key-value stores power caching, user sessions, and instant lookups—plus TTLs, eviction, scaling options, and practical trade-offs to watch.

Learn how key-value stores power caching, user sessions, and instant lookups—plus TTLs, eviction, scaling options, and practical trade-offs to watch.

The main goal of a key-value store is simple: reduce latency for end users and reduce load on your primary database. Instead of running the same expensive query or recomputing the same result, your app can fetch a precomputed value in a single, predictable step.

A key-value store is optimized around one operation: “given this key, return the value.” That narrow focus enables a very short critical path.

In many systems, a lookup can often be handled with:

The result is low and consistent response times—exactly what you want for caching, session storage, and other high-speed lookups.

Even if your database is well-tuned, it still has to parse queries, plan them, read indexes, and coordinate concurrency. If thousands of requests ask for the same “top products” list, that repeated work adds up.

A key-value cache shifts that repeated read traffic away from the database. Your database can spend more time on requests that truly require it: writes, complex joins, reporting, and consistency-critical reads.

Speed isn’t free. Key-value stores typically trade away rich querying (filters, joins) and may have different guarantees around persistence and consistency depending on configuration.

They shine when you can name data with a clear key (for example, user:123, cart:abc) and want quick retrieval. If you frequently need “find all items where X,” a relational or document database is usually a better primary store.

A key-value store is the simplest kind of database: you store a value (some data) under a unique key (a label), and later you fetch the value by providing the key.

Think of a key as an identifier that’s easy to repeat exactly, and a value as the thing you want back.

Keys are usually short strings (like user:1234 or session:9f2a...). Values can be small (a counter) or larger (a JSON blob).

Key-value stores are built for “give me the value for this key” queries. Internally, many use a structure similar to a hash table: the key is transformed into a location where the value can be found quickly.

That’s why you’ll often hear constant-time lookups (often written as O(1)): performance depends much more on how many requests you do than on how many total records exist. It’s not magic—collisions and memory limits still matter—but for typical cache/session use, it’s very fast.

Hot data is the small slice of information requested repeatedly (popular product pages, active sessions, rate-limit counters). Keeping hot data in a key-value store—especially in memory—avoids slower database queries and keeps response times predictable under load.

Caching means keeping a copy of frequently needed data somewhere faster to reach than the original source. A key-value store is a common place to do this because it can return a value in a single lookup by key, often in a few milliseconds.

Caching shines when the same questions get asked over and over: popular pages, repeated searches, common API calls, or expensive calculations. It’s also useful when the “real” source is slower or rate-limited—like a primary database under heavy load or a third-party API you pay for per request.

Good candidates are results that are read often and don’t need to be perfectly up-to-the-second:

A simple rule: cache outputs you can regenerate if needed. Avoid caching data that changes constantly or must be consistent across all reads (for example, a bank balance).

Without caching, every page view might trigger multiple database queries or API calls. With a cache, the application can serve many requests from the key-value store and only “fall back” to the primary database or API on a cache miss. That lowers query volume, reduces connection contention, and can improve reliability during traffic spikes.

Caching trades freshness for speed. If cached values aren’t updated quickly, users may see stale information. In distributed systems, two requests might briefly read different versions of the same data.

You manage these risks by choosing appropriate TTLs, deciding which data can be “slightly old,” and designing your application to tolerate occasional cache misses or refresh delays.

A cache “pattern” is a repeatable workflow for how your app reads and writes data when a cache is involved. Picking the right one depends less on the tool (Redis, Memcached, etc.) and more on how often the underlying data changes and how much stale data you can tolerate.

With cache-aside, your application controls the cache explicitly:

Best fit: data that is read often but changes infrequently (product pages, configuration, public profiles). It’s also a good default because failures degrade gracefully: if the cache is empty, you can still read from the database.

Read-through means the cache layer fetches from the database on a miss (your app reads “from cache,” and the cache knows how to load). Operationally, it simplifies app code, but it adds complexity to the cache tier (you need a loader integration).

Write-through means every write goes to the cache and the database synchronously. Reads are usually fast and consistent, but writes are slower because they must complete two operations.

Best fit: data where you want fewer cache misses and simpler read consistency (user settings, feature flags), and where write latency is acceptable.

With write-back, your app writes to the cache first, and the cache flushes changes to the database later (often in batches).

Benefits: very fast writes and reduced database load.

Added risk: if the cache node fails before flushing, you can lose data. Use this only when you can tolerate loss or have strong durability mechanisms.

If data changes rarely, cache-aside with a sensible TTL is usually enough. If data changes frequently and stale reads are painful, consider write-through (or very short TTLs plus explicit invalidation). If write volume is extreme and occasional loss is acceptable, write-behind can be worth the trade.

Keeping cached data “fresh enough” is mostly about choosing the right expiration strategy for each key. The goal isn’t perfect accuracy—it’s preventing stale results from surprising users while still getting the speed benefits of caching.

A TTL (time to live) sets an automatic expiry on a key so it disappears (or becomes unavailable) after a duration. Short TTLs reduce staleness but increase cache misses and backend load. Longer TTLs improve hit rate but risk serving outdated values.

A practical way to choose TTLs:

TTL is passive. When you know data has changed, it’s often better to actively invalidate: delete the old key or write the new value immediately.

Example: after a user updates their email, delete user:123:profile or update it in the cache right away. Active invalidation reduces staleness windows, but it requires your application to reliably perform those cache updates.

Instead of deleting old keys, include a version in the key name, like product:987:v42. When the product changes, bump the version and start writing/reading v43. Old versions naturally expire later. This avoids races where one server deletes a key while another is writing it.

A stampede happens when a popular key expires and many requests rebuild it at the same time.

Common fixes include:

Session data is the small bundle of information your app needs to recognize a returning browser or mobile client. At minimum, that’s a session ID (or token) that maps to server-side state. Depending on the product, it can also include user state (logged-in flags, roles, CSRF nonce), temporary preferences, and time-sensitive data like cart contents or a checkout step.

Key-value stores are a natural match because session reads and writes are simple: look up a token, fetch a value, update it, and set an expiration. They also make it easy to apply TTLs so inactive sessions disappear automatically, keeping storage tidy and reducing risk if a token is leaked.

A common flow:

Use clear, scoped keys and keep values small:

sess:<token> or sess:v2:<token> (versioning helps with future changes).user_sess:<userId> -> <token> to enforce “one active session per user” or to revoke sessions by user.Logout should delete the session key and any related indexes (like user_sess:<userId>). For rotation (recommended after login, privilege changes, or periodically), create a new token, write the new session, then delete the old key. This narrows the window where a stolen token remains useful.

Caching is the most common use case for a key-value store, but it’s not the only way it can speed up your system. Many applications rely on fast reads for small, frequently referenced pieces of state—things that are “source of truth adjacent” and need to be checked quickly on nearly every request.

Authorization checks often sit on the critical path: every API call may need to answer “is this user allowed to do this?” Pulling permissions from a relational database on every request can add noticeable latency and load.

A key-value store can hold compact authorization data for quick lookups, for example:

perm:user:123 → a list/set of permission codesentitlement:org:45 → enabled plan featuresThis is especially useful when your permissions model is read-heavy and changes relatively infrequently. When permissions do change (role updates, plan upgrades), you can update or invalidate a small set of keys so the next request reflects the new access rules.

Feature flags are small, frequently read values that need to be available quickly and consistently across many services.

A common pattern is storing:

flag:new-checkout → true/falseconfig:tax:region:EU → JSON blob or versioned configKey-value stores work well here because reads are simple, predictable, and extremely fast. You can also version values (for example, config:v27:...) to make rollouts safer and allow quick rollback.

Rate limiting often boils down to counters per user, API key, or IP address. Key-value stores typically support atomic operations, which let you increment a counter safely even when many requests arrive at once.

You might track:

rl:user:123:minute → increment each request, expire after 60 secondsrl:ip:203.0.113.10:second → short-window burst controlWith a TTL on each counter key, limits reset automatically without background jobs. This is a practical foundation for throttling login attempts, protecting expensive endpoints, or enforcing plan-based quotas.

Payments and other “do it exactly once” operations need protection from retries—whether caused by timeouts, client retries, or message re-delivery.

A key-value store can record idempotency keys:

idem:pay:order_789:clientKey_abc → stored result or statusOn the first request, you process and store the outcome with a TTL. On later retries, you return the stored outcome instead of executing the operation again. The TTL prevents unbounded growth while covering the realistic retry window.

These uses aren’t “caching” in the classic sense; they’re about keeping latency low for high-frequency reads and coordination primitives that need speed and atomicity.

A “key-value store” doesn’t always mean “string in, string out.” Many systems offer richer data structures that let you model common needs directly inside the store—often faster and with fewer moving parts than pushing everything into application code.

Hashes (also called maps) are ideal when you have a single “thing” with several related attributes. Instead of creating many keys like user:123:name, user:123:plan, user:123:last_seen, you can keep them together under one key, such as user:123 with fields.

This reduces key sprawl and lets you fetch or change only the field you need—useful for profiles, feature flags, or small configuration blobs.

Sets are great for “is X in the group?” questions:

Sorted sets add ordering by a score, which fits leaderboards, “top N” lists, and ranking by time or popularity. For example, you can store scores as view counts or timestamps and quickly read the top items.

Concurrency problems often show up in small features: counters, quotas, one-time actions, and rate limits. If two requests arrive at the same time and your app does “read → add 1 → write,” you can lose updates.

Atomic operations solve this by performing the change as a single, indivisible step inside the store:

With atomic increments, you don’t need locks or extra coordination between servers. That means fewer race conditions, simpler code paths, and more predictable behavior under load—especially for rate limiting and usage caps where “almost correct” quickly turns into customer-facing issues.

When a key-value store starts handling serious traffic, “making it faster” usually means “making it wider”: spreading reads and writes across multiple nodes while keeping the system predictable under failure.

Replication keeps multiple copies of the same data.

Sharding splits the keyspace across nodes.

Many deployments combine both: shards for throughput, replicas per shard for availability.

“High availability” generally means the cache/session layer keeps serving requests even if a node fails.

With client-side routing, your application (or its library) computes which node holds a key (common with consistent hashing). This can be very fast, but clients must learn about topology changes.

With server-side routing, you send requests to a proxy or cluster endpoint that forwards them to the right node. This simplifies clients and rollouts, but adds a hop.

Plan memory from the top down:

Key-value stores feel “instant” because they keep hot data in memory and optimize for fast reads/writes. That speed has a cost: you’re often choosing between performance, durability, and consistency. Understanding the trade-offs up front prevents painful surprises later.

Many key-value stores can run with different persistence modes:

Pick the mode that matches the data’s purpose: caching tolerates loss; session storage often needs more care.

In distributed setups, you may see eventual consistency—reads might briefly return an older value after a write, especially during failover or replication lag. Stronger consistency (for example, requiring acknowledgements from multiple nodes) reduces anomalies but increases latency and can reduce availability during network issues.

Caches fill up. An eviction policy decides what gets removed: least-recently-used, least-frequently-used, random, or “don’t evict” (which turns “full memory” into write failures). Decide whether you prefer missing cache entries or errors under pressure.

Assume outages happen. Typical fallbacks include:

Designing these behaviors intentionally is what makes the system feel reliable to users.

Key-value stores often sit on the “hot path” of your app. That makes them both sensitive (they may hold session tokens or user identifiers) and expensive (they’re usually memory-heavy). Getting the basics right early prevents painful incidents later.

Start with clear network boundaries: place the store in a private subnet/VPC segment, and only allow traffic from the application services that truly need it.

Use authentication if the product supports it, and follow least privilege: separate credentials for apps, admins, and automation; rotate secrets; and avoid shared “root” tokens.

Encrypt data in transit (TLS) whenever possible—especially if traffic crosses hosts or zones. Encryption at rest is product- and deployment-dependent; if supported, enable it for managed services and verify backup encryption too.

A small set of metrics tells you whether the cache is helping or hurting:

Add alerts for sudden changes, not just absolute thresholds, and log key operations carefully (avoid logging sensitive values).

The biggest drivers are:

A practical cost lever is reducing value size and setting realistic TTLs, so the store holds only what’s actively useful.

Start by standardizing key naming so your cache and session keys are predictable, searchable, and safe to operate on in bulk. A simple convention like app:env:feature:id (for example, shop:prod:cart:USER123) helps avoid collisions and makes debugging faster.

Define a TTL strategy before you ship. Decide which data is safe to expire quickly (seconds/minutes), what needs longer lifetimes (hours), and what should never be cached at all. If you’re caching database rows, align TTLs with how often the underlying data changes.

Write down an invalidation plan for each cached item type:

product:v3:123) when you want simple “invalidate everything” behaviorPick a few success metrics and track them from day one:

Also monitor eviction counts and memory usage to confirm your cache is sized appropriately.

Oversized values increase network time and memory pressure—prefer caching smaller, precomputed fragments. Avoid missing TTLs (stale data and memory leaks) and unbounded key growth (for example, caching every search query forever). Be careful caching user-specific data under shared keys.

If you’re evaluating options, compare a local in-process cache versus a distributed cache and decide where consistency matters most. For implementation details and operational guidance, review /docs. If you’re planning capacity or need pricing assumptions, see /pricing.

If you’re building a new product (or modernizing an existing one), it can help to design caching and session storage as first-class concerns from the start. On Koder.ai, teams often prototype an end-to-end app (React on the web, Go services with PostgreSQL, and optionally Flutter for mobile) and then iterate on performance with patterns like cache-aside, TTLs, and rate-limiting counters. Features like planning mode, snapshots, and rollback make it easier to try cache key designs and invalidation strategies safely, and you can export the source code when you’re ready to run it in your own pipeline.

Key-value stores optimize for one operation: given a key, return a value. That narrow focus enables fast paths like in-memory indexing and hashing, with less query planning overhead than general-purpose databases.

They also speed up your system indirectly by offloading repeated reads (popular pages, common API responses) so your primary database can focus on writes and complex queries.

A key is a unique identifier you can repeat exactly (often a string like user:123 or sess:<token>). The value is whatever you want back—anything from a small counter to a JSON blob.

Good keys are stable, scoped, and predictable, which makes caching, sessions, and lookups straightforward to operate and debug.

Cache results that are read frequently and safe to regenerate if missing.

Common examples:

Avoid caching data that must be perfectly current (e.g., financial balances) unless you have a strong invalidation strategy.

Cache-aside (lazy loading) is usually the default:

key from cache.It degrades gracefully: if the cache is empty or down, you can still serve requests from the database (with appropriate safeguards).

Use read-through when you want the cache layer to automatically load on misses (simpler application reads, more cache-tier integration).

Use write-through when you want reads to be more consistently warm because every write updates both cache and database synchronously—at the cost of higher write latency.

Pick them when you can accept the operational complexity (read-through) or the extra write time (write-through).

A TTL automatically expires a cached value after a duration. Short TTLs reduce staleness but raise miss rates and backend load; longer TTLs improve hit rate but increase the risk of serving outdated data.

Practical tips:

A cache stampede happens when a hot key expires and many requests recompute it simultaneously.

Common mitigations:

These reduce sudden spikes to your database or external APIs.

Sessions are a strong fit because access is simple: read/write by token and apply expiration.

Good practices:

sess:<token> (versioning like sess:v2:<token> helps migrations).Many key-value stores support atomic increment operations, which makes counters safe under concurrency.

A typical pattern:

rl:user:123:minute → increment per requestIf the counter exceeds your threshold, throttle or reject the request. TTL-based expiration resets limits automatically without background jobs.

Key trade-offs to plan for:

Design for degraded mode: be ready to bypass cache, serve slightly stale data when safe, or fail closed for sensitive operations.