Jun 13, 2025·8 min

Kent Beck & Extreme Programming: TDD, Iteration, Feedback

Explore how Kent Beck and Extreme Programming popularized TDD, short iterations, and feedback loops—and why these ideas still guide teams today.

Why Kent Beck and XP Still Matter

Kent Beck’s Extreme Programming (XP) is sometimes treated like a period piece from the early web era: interesting, influential, and slightly out of date. But many of the habits that make modern software teams effective—shipping frequently, getting fast signals from users, keeping code easy to change—map directly to XP’s core ideas.

This article’s goal is simple: explain where XP came from, what it was trying to fix, and why its best parts still hold up. It’s not a tribute, and it’s not a ruleset you must follow. Think of it as a practical tour of principles that still show up in healthy engineering teams.

Three recurring themes

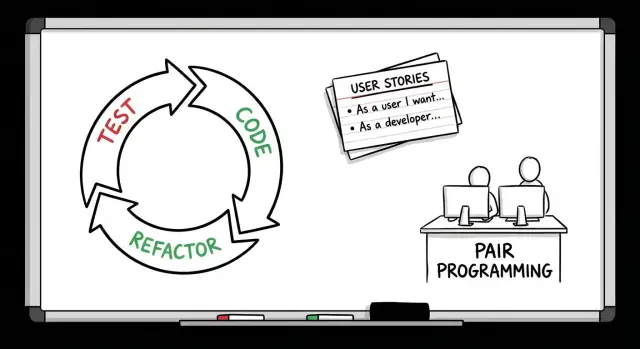

XP is a bundle of practices, but three themes show up again and again:

- TDD (Test-Driven Development): using tests not just to prevent bugs, but to shape design by forcing clarity about what code should do.

- Iteration: delivering work in small, frequent batches so you can learn sooner and avoid long stretches of unvalidated effort.

- Feedback loops: creating short cycles of “try → observe → adjust” through tests, pairing, integration, and real user outcomes.

Who this is for

If you’re an engineer, tech lead, engineering manager, or product-minded reader who collaborates closely with developers, XP offers a shared vocabulary for what “moving fast without breaking everything” can look like in practice.

What you’ll take away

By the end, you should be able to:

- Recognize the intent behind XP practices (not just the rituals).

- Apply a few high-leverage techniques—like smaller iterations, tighter feedback, and purposeful refactoring—without adopting “full XP.”

- Avoid common misreads (for example, treating TDD as box-checking, or iteration as constant churn).

XP still matters because it treats software development as a learning problem, not a prediction problem—and it gives teams concrete ways to learn faster.

Kent Beck in Context: What Problem Was XP Solving?

Kent Beck is often introduced as the person who named Extreme Programming (XP) and later helped shape the Agile movement. But XP didn’t start as a theory exercise. It was a practical response to a specific kind of pain: projects where requirements kept changing, software kept breaking, and teams kept learning the “real” problems only after it was too late.

The project pressures that produced XP

XP emerged from real delivery constraints—tight timelines, evolving scope, and the growing cost of late surprises. Teams were being asked to build complex systems while the business was still figuring out what it needed. Traditional plans assumed stability: gather requirements up front, design everything, implement, then test near the end. When that stability wasn’t there, the plan collapsed.

What XP was reacting against

The main enemy XP targeted wasn’t “documentation” or “process” in general—it was late feedback.

Heavy, phase-gated methods tended to delay learning:

- Customers saw working software late, so wrong assumptions survived for months.

- Testing happened late, so defects piled up and became expensive to fix.

- Integration happened late, so teams discovered conflicts when the schedule had no room left.

XP flipped the order: shorten the time between action and information. That’s why practices like Test-Driven Development (TDD), continuous integration, refactoring, and pair programming fit together—they’re all feedback loops.

XP is more than “move fast”

Calling it “Extreme” was a reminder to push good ideas further: test earlier, integrate more often, communicate continuously, improve design as you learn. XP is a set of practices guided by values (like communication and simplicity), not permission to cut corners. The goal is sustainable speed: build the right thing, and keep it working as change continues.

The Values Behind the Practices

Extreme Programming (XP) isn’t a grab bag of engineering tricks. Kent Beck framed it as a set of values that guide decisions when the codebase is changing every day. The practices—TDD, pair programming, refactoring, continuous integration—make more sense when you see what they’re trying to protect.

The five XP values (in plain terms)

Communication means “don’t let knowledge get trapped in one person’s head.” That’s why XP leans on pair programming, shared code ownership, and small, frequent check-ins. If a design decision matters, it should be visible in conversation and in the code—not hidden in a private mental model.

Simplicity means “do the simplest thing that works today.” This shows up in small releases and refactoring: build what you need now, keep it clean, and let real usage shape what’s next.

Feedback means “learn fast.” XP turns feedback into a daily habit through Test-Driven Development (TDD) (instant feedback on correctness and design), continuous integration (fast feedback on integration risk), and regular customer/team review.

Courage means “make the change that improves the system, even if it’s uncomfortable.” Courage is what makes refactoring and deleting dead code normal, not scary. Good tests and CI make that courage rational.

Respect means “work in a way that’s sustainable for people.” It’s behind practices like pairing (support), reasonable pace, and treating code quality as a shared responsibility.

How values steer real tradeoffs

A common XP choice: you can build a flexible framework “just in case,” or implement a straightforward solution now. XP chooses simplicity: ship the simple version with tests, then refactor when a real second use case arrives. That’s not laziness—it’s a bet that feedback beats speculation.

The Origin Story of TDD: From Testing to Design Feedback

Before Extreme Programming (XP), testing often meant a separate phase near the end of a project. Teams would build features for weeks or months, then hand them to QA or do a big manual “test pass” right before release. Bugs were discovered late, fixes were risky, and the feedback cycle was slow: by the time a defect showed up, the code had already grown around it.

From “test later” to test-first discipline

Kent Beck’s push with Test-Driven Development (TDD) was a simple but radical habit: write a test first, watch it fail, then write the smallest change to make it pass. That “failing test first” rule isn’t theater—it forces you to clarify what you want the code to do before you decide how it should do it.

Red–Green–Refactor in plain terms

TDD is usually summarized as Red–Green–Refactor:

- Red: Write a test for a tiny behavior. Example: “When I add two items priced 5 and 7, the total is 12.” Run tests and see it fail.

- Green: Implement the simplest code that makes the test pass (maybe a basic

total()function that sums item prices). - Refactor: Clean up the code without changing behavior—rename variables, remove duplication, improve structure—then rerun tests to stay confident.

Why it wasn’t just “more tests”

The deeper shift was treating tests as a design feedback tool, not a safety net added at the end. Writing the test first nudges you toward smaller, clearer interfaces, fewer hidden dependencies, and code that’s easier to change. In XP terms, TDD tightened the feedback loop: every few minutes, you learn whether your design direction is working—while the cost of changing your mind is still low.

What TDD Changed in Everyday Engineering

TDD didn’t just add “more tests.” It changed the order of thinking: write a small expectation first, then write the simplest code that satisfies it, then clean up. Over time that habit shifts engineering from heroic debugging to steady, low-drama progress.

What “good” unit tests look like

The unit tests that support TDD well tend to share a few traits:

- Fast: they run in milliseconds and are runnable constantly—locally, before every commit.

- Focused: each test checks one behavior; failures point to a specific problem.

- Readable: the test name and setup explain intent (“what should happen”) more than mechanics (“how it happens”).

A helpful rule: if you can’t quickly tell why a test exists, it’s not pulling its weight.

TDD’s quiet impact on API design

Writing the test first makes you the caller before you’re the implementer. That often leads to cleaner interfaces because friction shows up immediately:

- Awkward constructors and too many parameters become obvious.

- Hidden dependencies (globals, singletons, time, randomness) force you to add seams.

- You naturally design smaller, composable functions because they’re easier to exercise.

In practice, TDD nudges teams toward APIs that are easier to use, not just easier to build.

Common misunderstandings

Two myths cause a lot of disappointment:

- “TDD means testing everything.” It means testing the valuable behaviors at the right level. Some code is better validated with integration tests or even simple assertions.

- “If we do TDD, we don’t need integration tests.” Unit tests protect small behavior; integration tests protect wiring, configuration, and real dependencies.

Where TDD is hardest (and what to do instead)

TDD can be painful in legacy code (tight coupling, no seams) and UI-heavy code (event-driven, stateful, lots of framework glue). Instead of forcing it:

- For legacy code, start with characterization tests around existing behavior, then refactor in small steps.

- For UI-heavy areas, push logic into testable units, and rely more on integration/acceptance tests for the boundaries.

Used this way, TDD becomes a practical design feedback tool—not a purity test.

Iteration: Shipping in Small Batches

Get to a Live Demo

Deploy and host your build as you iterate, without waiting for a long release cycle.

Iteration in Extreme Programming (XP) means delivering work in small, time-boxed slices—batches that are small enough to finish, review, and learn from quickly. Instead of treating release as a rare event, XP treats delivery as a frequent checkpoint: build something small, prove it works, get feedback, then decide what to do next.

Why shorter cycles reduce risk

Big upfront plans assume you can predict needs, complexity, and edge cases months in advance. In real projects, requirements shift, integrations surprise you, and “simple” features reveal hidden costs.

Short iterations reduce that risk by limiting how long you can be wrong. If an approach doesn’t work, you find out in days—not quarters. It also makes progress visible: stakeholders see real increments of value rather than status reports.

Lightweight planning: user stories + acceptance criteria

XP iteration planning is intentionally simple. Teams often use user stories—short descriptions of value from a user’s perspective—and add acceptance criteria to define “done” in plain language.

A good story answers: who wants what, and why? Acceptance criteria describe observable behavior (“When I do X, the system does Y”), which helps everyone align without writing a giant specification.

Practical cadence examples (and what to review)

A common XP cadence is weekly or biweekly:

- Weekly iterations work well when the domain is uncertain or feedback is crucial. You keep scope small: a couple of stories, a thin vertical slice, and a quick release.

- Biweekly iterations give a bit more room for multi-step work, while still forcing regular integration and review.

At the end of each iteration, teams typically review:

- What shipped (a demo of working software)

- Whether acceptance criteria were met

- What feedback changed priorities

- What slowed the team down (a small retro with one or two concrete improvements)

The goal isn’t ceremony—it’s a steady rhythm that turns uncertainty into informed next steps.

Feedback Loops: The Engine of XP

Extreme Programming (XP) is often described through its practices—tests, pairing, continuous integration—but the unifying idea is simpler: shorten the time between making a change and learning whether it was a good one.

Where feedback actually comes from

XP stacks multiple feedback channels so you’re never waiting long to find out you’re off-track:

- Tests (especially unit tests): immediate signal that behavior still holds.

- Code review / pairing: a second set of eyes catches misunderstandings while they’re cheap.

- CI builds: the team learns quickly if changes break integration, not days later.

- Customer demos (or stakeholder check-ins): validates whether you built the right thing, not just whether it “works.”

Why fast feedback beats perfect prediction

Prediction is expensive and often wrong because real requirements and real constraints show up late. XP assumes you won’t foresee everything, so it optimizes for learning early—when changing direction is still affordable.

A fast loop turns uncertainty into data. A slow loop turns uncertainty into arguments.

Idea → Code → Test → Learn → Adjust → (repeat)

The cost of slow feedback

When feedback takes days or weeks, problems compound:

- Rework grows: you build more on top of a wrong assumption.

- Defects harden: small bugs become systemic issues once copied and depended on.

- Expectations drift: stakeholders imagine one outcome while the team ships another.

XP’s “engine” isn’t any single practice—it’s the way these loops reinforce each other to keep work aligned, quality high, and surprises small.

Pair Programming as Real-Time Quality Control

Choose a Plan That Fits

Pick a tier that matches your team, from free to enterprise.

Pair programming is often described as “two people, one keyboard,” but the real idea in Extreme Programming is continuous review. Instead of waiting for a pull request, feedback happens minute by minute: naming, edge cases, architecture choices, and even whether a change is worth making.

Continuous review + shared context

With two minds on the same problem, small mistakes get caught while they’re still cheap. The navigator notices the missing null check, the unclear method name, or the risky dependency before it turns into a bug report.

Just as importantly, pairing spreads context. The codebase stops feeling like a set of private territories. When knowledge is shared in real time, the team doesn’t rely on a few people who “know how it works,” and onboarding becomes less of a scavenger hunt.

Feedback benefits you can feel

Because the feedback loop is immediate, teams often see fewer defects escaping to later stages. Design also improves: it’s harder to rationalize a complicated approach when you have to explain it out loud. The act of narrating decisions tends to surface simpler designs, smaller functions, and clearer boundaries.

Common concerns (and how XP teams handle them)

- “Isn’t it twice the cost?” Not if it prevents rework, long reviews, and production issues. You’re trading later cleanup for earlier clarity.

- Fatigue: Pairing all day can be draining. Many teams pair selectively (new feature work, tricky refactors) and allow solo time for routine tasks.

- Mismatched skill levels: That’s normal. Done well, it’s mentoring without a formal meeting—while still shipping.

Practical pairing patterns

Driver/Navigator: One writes code, the other reviews, thinks ahead, and asks questions. Swap roles regularly.

Rotating pairs: Change partners daily or per story to prevent knowledge silos.

Time-boxed sessions: Pair for 60–90 minutes, then take a break or switch tasks. This keeps focus high and reduces burnout.

Refactoring: Keeping Code Healthy as It Grows

Refactoring is the practice of changing code’s internal structure without changing what the software does. In XP, it wasn’t treated as an occasional cleanup day—it was routine work, done in small steps, alongside feature development.

Why XP made refactoring a habit

XP assumed that requirements would change, and that the best way to stay responsive is to keep the code easy to change. Refactoring prevents “design decay”: the slow buildup of confusing names, tangled dependencies, and copy‑pasted logic that makes every future change slower and riskier.

How TDD makes refactoring safe

Refactoring is only comfortable when you have a safety net. Test-Driven Development supports refactoring by building a suite of fast, repeatable tests that tell you if behavior changed by accident. When tests are green, you can rename, reorganize, and simplify with confidence; when they fail, you get quick feedback about what you broke.

Common refactoring goals

Refactoring isn’t about cleverness—it’s about clarity and flexibility:

- Readability: better names, smaller functions, clearer intent.

- Removing duplication: one well-named piece of logic instead of three slightly different copies.

- Clearer boundaries: isolating responsibilities so changes don’t ripple everywhere (e.g., separating business rules from database or UI code).

Anti-patterns to avoid

Two mistakes show up repeatedly:

- Refactoring without tests: you’re “improving” code while flying blind, so teams become afraid to touch it.

- A “big rewrite” disguised as refactor: behavior changes, timelines explode, and you lose the steady learning XP depends on. Refactoring should be incremental, verifiable, and reversible—small steps that keep the system healthy while it grows.

Continuous Integration: Catch Issues While They’re Small

Continuous Integration (CI) is an XP idea with a simple goal: merge work frequently so problems show up early, when they’re still cheap to fix. Instead of each person building features in isolation for days (or weeks) and then “finding out” at the end that things don’t fit together, the team keeps the software in a state where it can be brought together safely—many times a day.

CI in XP terms: integrate often

XP treats integration as a form of feedback. Every merge answers practical questions: Did we accidentally break something? Do our changes still work with everyone else’s changes? When the answer is “no,” you want to learn that within minutes, not at the end of an iteration.

What a pipeline does (without the jargon)

A build pipeline is basically a repeatable checklist that runs whenever code changes:

- It assembles the product (so you know it still “builds”).

- It runs automated checks (so you know key behaviors still work).

- It reports results quickly (so you can fix issues while the context is fresh).

Even for non-technical stakeholders, the value is easy to feel: fewer surprise breakages, smoother demos, and less last-minute thrash.

Why it speeds up iterations

When CI is working well, teams can ship smaller batches with more confidence. That confidence changes behavior: people are more willing to make improvements, refactor safely, and deliver incremental value instead of hoarding changes.

Modern additions (without dogma)

Today’s CI often includes richer automated checks (security scans, style checks, performance smoke tests) and workflows like trunk-based development, where changes are kept small and integrated quickly. The point isn’t to follow a single “correct” template—it’s to keep feedback fast and integration routine.

Critiques, Misuse, and When to Adapt XP

Test Ideas on Mobile

Describe a Flutter app in chat and iterate on flows without big rewrites.

XP attracts strong opinions because it’s unusually explicit about discipline. That’s also why it’s easy to misunderstand.

The usual pushback (and what’s true in it)

You’ll often hear: “XP is too strict” or “TDD slows us down.” Both can be true—briefly.

XP practices add friction on purpose: writing a test first, pairing, or integrating constantly feels slower than “just coding.” But that friction is meant to prevent a bigger tax later: unclear requirements, rework, brittle code, and long debugging cycles. The real question isn’t speed today; it’s whether you can keep shipping next month without the codebase fighting you.

When XP fits best—and when to adapt it

XP shines when requirements are uncertain and learning is the main job: early products, messy domains, evolving customer needs, or teams trying to shorten the time between an idea and real feedback. Small iterations and tight feedback loops reduce the cost of being wrong.

You may need to adapt when work is more constrained: regulated environments, heavy dependencies, or teams with many specialists. XP doesn’t require purity. It requires honesty about what gives you feedback—and what hides problems.

Common failure modes

The biggest failures aren’t “XP didn’t work,” but:

- Skipping the feedback practices (tests, customer review, CI) while keeping the meetings

- Cargo-culting rituals (“we pair” or “we do standups”) without changing how decisions get validated

- Treating TDD as bureaucracy instead of design feedback

Starting small

Pick one loop and strengthen it:

- If quality hurts: start with tests around the most change-prone code.

- If direction hurts: shorten iteration cycles and add real review/demo moments.

Once one loop is reliable, add the next. XP is a system, but you don’t have to adopt it all at once.

The Lasting Cultural Impact: XP’s Ideas in Modern Teams

XP is often remembered for specific practices (pairing, TDD, refactoring), but its bigger legacy is cultural: a team that treats quality and learning as daily work, not a phase at the end.

How XP quietly shaped “modern” ways of working

A lot of what teams now call Agile, DevOps, continuous delivery, and even product discovery echoes XP’s core moves:

- Shrink the batch: ship smaller changes more often to reduce risk.

- Tighten feedback: get signals from tests, peers, and production sooner.

- Make work visible: favor simple plans you can update over “perfect” predictions.

Even when teams don’t label it “XP,” you’ll see the same patterns in trunk-based development, CI pipelines, feature flags, lightweight experiments, and frequent customer touchpoints.

XP in the age of AI-assisted building

One reason XP still feels current is that its “learning loops” apply just as well when you’re using modern tooling. If you’re experimenting with a product idea, tools like Koder.ai can compress the iteration cycle even further: you can describe a feature in chat, generate a working web app (React) or backend service (Go + PostgreSQL), and then use real usage to refine the next story.

The XP-friendly part isn’t “magic code generation”—it’s the ability to keep batches small and reversible. For example, Koder.ai’s planning mode helps clarify intent before implementation (similar to writing acceptance criteria), and snapshots/rollback make it safer to refactor or try a risky change without turning it into a big-bang rewrite.

Enduring cultural effects

XP nudges teams toward:

- Shared ownership: code belongs to the team, so improvements don’t wait for “the one person.”

- A learning orientation: mistakes are information; the system changes so the mistake is harder to repeat.

- Quality as a habit: tests, refactoring, and review aren’t “extra,” they’re how work gets done.

A practical mini-checklist (use it this week)

- Can you get a test or build result in minutes, not hours?

- Can you deliver in hours/days, not weeks?

- Do you refactor in small steps as part of normal work?

- Do you have a real feedback ritual (pairing, review, or mobbing) on important changes?

- Does CI fail fast, and does the team treat red builds as urgent?

If you want to keep exploring, browse more essays in /blog, or see what a lightweight adoption plan could look like on /pricing.