Sep 22, 2025·6 min

Keep generated code maintainable: the boring architecture rule

Learn how to keep generated code maintainable using the boring architecture rule: clear folder boundaries, consistent naming, and simple defaults that reduce future rework.

Why maintainability is harder with generated code

Generated code changes the day-to-day job. You’re not only building features, you’re guiding a system that can create lots of files quickly. The speed is real, but small inconsistencies multiply fast.

Generated output often looks fine in isolation. The costs show up on the second and third change: you can’t tell where a piece belongs, you fix the same behavior in two places, or you avoid touching a file because you don’t know what else it affects.

“Clever” structure gets expensive because it’s hard to predict. Custom patterns, hidden magic, and heavy abstraction make sense on day one. On week six, the next change slows down because you have to re-learn the trick before you can update it safely. With AI-assisted generation, that cleverness can also confuse future generations and lead to duplicated logic or new layers stacked on top.

Boring architecture is the opposite: plain boundaries, plain names, and obvious defaults. It’s not about perfection. It’s about choosing a layout a tired teammate (or future you) can understand in 30 seconds.

A simple goal: make the next change easy, not impressive. That usually means one clear place for each kind of code (UI, API, data, shared utilities), predictable names that match what a file does, and minimal “magic” like auto-wiring, hidden globals, or metaprogramming.

Example: if you ask Koder.ai to add “team invites,” you want it to put UI in the UI area, add one API route in the API area, and store invite data in the data layer, without inventing a new folder or pattern just for that feature. That boring consistency is what keeps future edits cheap.

The boring architecture rule

Generated code gets expensive when it gives you many ways to do the same thing. The boring architecture rule is simple: make the next change predictable, even if the first build feels less clever.

You should be able to answer these quickly:

- Where does this feature live?

- Where do I put a new file?

- What should I name it?

- What’s the simplest path from UI to data?

The rule

Pick one plain structure and stick to it everywhere. When a tool (or a teammate) suggests a fancy pattern, the default answer is “no” unless it removes real pain.

Practical defaults that hold up over time:

- One responsibility per folder and per file. If a file has two reasons to change, split it.

- Predictability beats flexibility. The same kind of thing goes in the same place, every time.

- Prefer the standard approach of your stack over custom mini-frameworks.

- Make the happy path obvious. New contributors should guess the right location without asking.

- Reject “magic.” Avoid hidden behavior, reflection-heavy tricks, and clever abstractions.

A quick mental test

Imagine a new developer opens your repo and needs to add a “Cancel subscription” button. They shouldn’t have to learn a custom architecture first. They should find a clear feature area, a clear UI component, a single API client location, and a single data access path.

This rule works especially well with vibe-coding tools like Koder.ai: you can generate fast, but you still guide the output into the same boring boundaries every time.

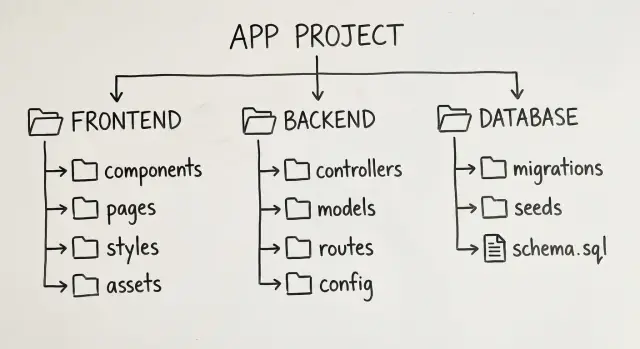

Simple folder boundaries that scale

Generated code tends to grow quickly. The safest way to keep it maintainable is a boring folder map where anyone can guess where a change belongs.

A small top-level layout that fits many web apps:

app/screens, routing, and page-level statecomponents/reusable UI piecesfeatures/one folder per feature (billing, projects, settings)api/API client code and request helpersserver/backend handlers, services, and business rules

This makes boundaries obvious: UI lives in app/ and components/, API calls live in api/, and backend logic lives in server/.

Data access should be boring too. Keep SQL queries and repository code near the backend, not scattered through UI files. In a Go + PostgreSQL setup, a simple rule is: HTTP handlers call services, services call repositories, repositories talk to the database.

Shared types and utilities deserve a clear home, but keep it small. Put cross-cutting types in types/ (DTOs, enums, shared interfaces) and small helpers in utils/ (date formatting, simple validators). If utils/ starts to feel like a second app, the code probably belongs in a feature folder instead.

Generated vs hand-written code

Treat generated folders as replaceable.

- Put generated output in

generated/(orgen/) and avoid editing it directly. - Keep custom logic in

features/orserver/so regeneration doesn’t overwrite it. - If you must patch generated behavior, wrap it (adapter file) instead of modifying the source.

Example: if Koder.ai generates an API client, store it under generated/api/, then write thin wrappers in api/ where you can add retries, logging, or clearer error messages without touching generated files.

Naming conventions that prevent confusion

Generated code is easy to create and easy to pile up. Naming is what keeps it readable a month later.

Pick one naming style and don’t mix it:

- Folders and files:

kebab-case(user-profile-card.tsx,billing-settings) - React components:

PascalCase(UserProfileCard) - Functions and variables:

camelCase(getUserProfile) - Constants:

SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASE(MAX_RETRY_COUNT)

Name by role, not by how it works today. user-repository.ts is a role. postgres-user-repository.ts is an implementation detail that might change. Only use implementation suffixes when you truly have multiple implementations.

Avoid junk drawers like misc, helpers, or a giant utils. If a function is only used by one feature, keep it near that feature. If it’s shared, make the name describe the capability (date-format.ts, money-format.ts, id-generator.ts) and keep the module small.

Conventions that make navigation fast

When routes, handlers, and components follow a pattern, you can find things without searching:

- Routes:

routes/users.tswith paths like/users/:userId - Handlers (HTTP):

handlers/users.get.ts,handlers/users.update.ts - Services (business rules):

services/user-profile-service.ts - Data access:

repositories/user-repository.ts - UI components:

components/user/UserProfileCard.tsx

If you use Koder.ai (or any generator), put these rules in the prompt and keep them consistent during edits. The point is predictability: if you can guess the file name, future changes stay cheaper.

No-cleverness defaults (rules of thumb)

Get rewarded for teaching

Earn credits by sharing what you built with Koder.ai and the conventions you used.

Generated code can look impressive on day one and painful on day thirty. Choose defaults that make the code obvious, even when it’s a bit repetitive.

Start by reducing magic. Skip dynamic loading, reflection-style tricks, and auto-wiring unless there’s a measured need. These features hide where things come from, which makes debugging and refactoring slower.

Prefer explicit imports and clear dependencies. If a file needs something, import it directly. If modules need wiring, do it in one visible place (for example, a single composition file). A reader shouldn’t have to guess what runs first.

Keep configuration boring and centralized. Put environment variables, feature flags, and app-wide settings in one module with one naming scheme. Don’t scatter config across random files because it felt convenient.

Rules of thumb that keep teams consistent:

- Choose explicit over implicit (imports, routing, DI, side effects).

- If it saves 10 lines but adds a new concept, skip it.

- Keep one way to do things (one logging tool, one config module).

- Prefer simple data flow over hidden observers or event chains.

- When debugging, delete clever code first.

Error handling is where cleverness hurts most. Pick one pattern and use it everywhere: return structured errors from the data layer, map them to HTTP responses in one place, and translate them into user-facing messages at the UI boundary. Don’t throw three different error types depending on the file.

If you generate an app with Koder.ai, ask for these defaults up front: explicit module wiring, centralized config, and one error pattern.

Boundaries between UI, API, and data

Clear lines between UI, API, and data keep changes contained. Most mystery bugs happen when one layer starts doing another layer’s job.

UI: show state, collect input

Treat the UI (often React) as a place to render screens and manage UI-only state: which tab is open, form errors, loading spinners, and basic input handling.

Keep server state separate: fetched lists, cached profiles, and anything that must match the backend. When UI components start calculating totals, validating complex rules, or deciding permissions, logic spreads across screens and becomes expensive to change.

API: thin, stable shapes

Keep the API layer predictable. It should translate HTTP requests into calls to business code, then translate results back into stable request/response shapes. Avoid sending database models directly over the wire. Stable responses let you refactor internals without breaking the UI.

A simple path that works well:

- UI calls an API client with typed request/response objects.

- API handlers validate input and call a service method.

- Services hold business rules and workflows.

- Repositories hide database queries behind small methods.

Data: hide queries behind repositories

Put SQL (or ORM logic) behind a repository boundary so the rest of the app doesn’t “know” how data is stored. In Go + PostgreSQL, that usually means repositories like UserRepo or InvoiceRepo with small, clear methods (GetByID, ListByAccount, Save).

Concrete example: adding discount codes. The UI renders a field and shows the updated price. The API accepts code and returns {total, discount}. The service decides if the code is valid and how discounts stack. The repository fetches and persists the required rows.

Step by step: set up maintainable generated code

Generated apps can look “done” quickly, but structure is what keeps changes cheap later. Decide boring rules first, then generate only enough code to prove them.

A practical setup flow

Start with a short planning pass. If you use Koder.ai, Planning Mode is a good place to write a folder map and a few naming rules before generating anything.

Then follow this sequence:

- Define the map and rules in writing. Pick boundaries (for example:

ui/,api/,data/,features/) and a handful of naming rules. - Generate one thin vertical slice. Choose a small feature that touches UI, API, and storage, like “create a contact.” The goal is the end-to-end path, not completeness.

- Refactor immediately to match boundaries. Move code into the planned folders, rename unclear files, and delete duplicates. Split “does everything” functions into UI, handler, and data access.

- Add a second feature to test the shape. Pick something similar, like “list contacts.” If you feel forced to break your rules, the boundaries are probably wrong.

- Lock conventions early. Add a short

CONVENTIONS.mdand treat it like a contract. Once the codebase grows, changing names and folder patterns gets expensive.

Reality check: if a new person can’t guess where to put “edit contact” without asking, the architecture still isn’t boring enough.

Example scenario: adding a feature without making a mess

Ship a clean vertical slice

Generate one thin feature end to end, then reuse the same structure for every change.

Picture a simple CRM: a contacts list page and a contact edit form. You build the first version fast, then a week later you need to add “tags” to contacts.

Treat the app like three boring boxes: UI, API, and data. Each box gets clear boundaries and literal names so the “tags” change stays small.

A clean layout could look like this:

web/src/pages/ContactsPage.tsxandweb/src/components/ContactForm.tsxserver/internal/http/contacts_handlers.goserver/internal/service/contacts_service.goserver/internal/repo/contacts_repo.goserver/migrations/

Now “tags” becomes predictable. Update the schema (new contact_tags table or a tags column), then touch one layer at a time: repo reads/writes tags, service validates, handler exposes the field, UI renders and edits it. Don’t sneak SQL into handlers or business rules into React components.

If product later asks for “filter by tag,” you’ll mostly work in ContactsPage.tsx (UI state and query params) and the HTTP handler (request parsing), while the repo handles the query.

For tests and fixtures, keep things small and close to the code:

server/internal/service/contacts_service_test.gofor rules like “tag names must be unique per contact”server/internal/repo/testdata/for minimal fixturesweb/src/components/__tests__/ContactForm.test.tsxfor form behavior

If you’re generating this with Koder.ai, the same rule applies after export: keep folders boring, keep names literal, and edits stop feeling like archaeology.

Common mistakes that make future changes expensive

Generated code can look clean on day one and still be costly later. The usual culprit isn’t “bad code,” it’s inconsistency.

One expensive habit is letting the generator invent structure each time. A feature lands with its own folders, naming style, and helper functions, and you end up with three ways to do the same thing. Pick one pattern, write it down, and treat any new pattern as a conscious change, not a default.

Another trap is mixing layers. When a UI component talks to the database, or an API handler builds SQL, small changes turn into risky edits across the app. Keep the boundary: UI calls an API, the API calls a service, the service calls data access.

Overusing generic abstractions too early also adds cost. A universal “BaseService” or “Repository” framework feels neat, but early abstractions are guesses. When reality changes, you fight your own framework instead of shipping.

Constant renaming and reorganizing is a quieter form of debt. If files move every week, people stop trusting the layout and quick fixes land in random places. Stabilize the folder map first, then refactor in planned chunks.

Finally, be careful with “platform code” that has no real user. Shared libraries and homegrown tooling only pay off when you have repeated, proven needs. Until then, keep defaults direct.

A quick checklist before you ship

Refer and earn credits

Use your referral link to bring others in and earn credits while you build.

If someone new opens the repo, they should be able to answer one question fast: “Where do I add this?”

2-minute navigation test

Hand the project to a teammate (or future you) and ask them to add a tiny feature, like “add a field to the signup form.” If they can’t find the right place quickly, the structure isn’t doing its job.

Check for three clear homes:

- UI changes live in one obvious place.

- API routes/handlers are easy to find from the UI.

- Data model and database changes have a clear location.

Rules worth enforcing in review

- UI, API, and data each have a home, and exceptions are rare.

- Names read like labels, not puzzles.

- Layer breaks get flagged (like UI reaching into the database).

- Clever shortcuts get rejected by default.

If your platform supports it, keep a rollback path. Snapshots and rollback are especially useful when you’re experimenting with structure and want a safe way back.

Next steps: keep it boring, keep it cheap

Maintainability improves fastest when you stop debating style and start making a few decisions that stick.

Write down a small set of conventions that remove daily hesitation: where files go, how they’re named, and how errors and config are handled. Keep it short enough to read in one minute.

Then do one cleanup pass to match those rules and stop reshuffling weekly. Frequent reorganizing makes the next change slower, even if the code looks nicer.

If you’re building with Koder.ai (koder.ai), it helps to save these conventions as a starting prompt so each new generation lands in the same structure. The tool can move fast, but the boring boundaries are what keep the code easy to change.