Dec 13, 2025·8 min

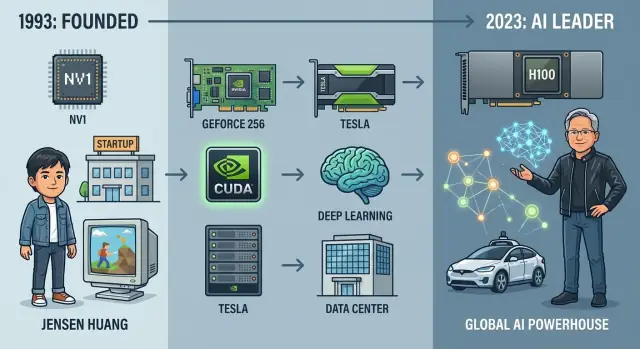

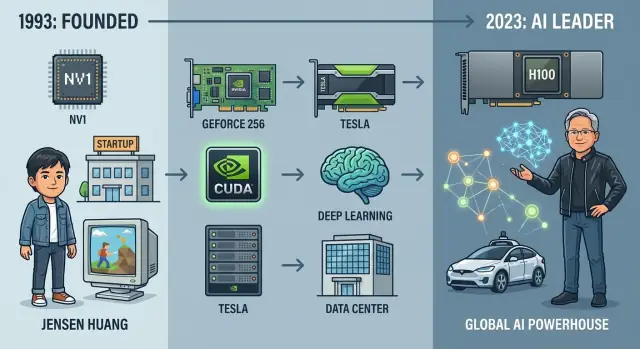

From Graphics Startup to AI Titan: The History of Nvidia

Explore Nvidia's journey from 1993 graphics start-up to a global AI powerhouse, tracing key products, breakthroughs, leaders, and strategic bets.

Explore Nvidia's journey from 1993 graphics start-up to a global AI powerhouse, tracing key products, breakthroughs, leaders, and strategic bets.

Nvidia has become a household name for very different reasons, depending on who you ask. PC gamers think of GeForce graphics cards and silky‑smooth frame rates. AI researchers think of GPUs that train frontier models in days instead of months. Investors see one of the most valuable semiconductor companies in history, a stock that became a proxy for the entire AI boom.

Yet this wasn’t inevitable. When Nvidia was founded in 1993, it was a tiny startup betting on a niche idea: that graphics chips would reshape personal computing. Over three decades, it evolved from a scrappy graphics card maker into the central supplier of hardware and software for modern AI, powering everything from recommendation systems and self‑driving prototypes to giant language models.

Understanding Nvidia’s history is one of the clearest ways to understand modern AI hardware and the business models forming around it. The company sits at the junction of several forces:

Along the way, Nvidia has repeatedly made high‑risk bets: backing programmable GPUs before there was a clear market, building a full software stack for deep learning, and spending billions on acquisitions like Mellanox to control more of the data center.

This article traces Nvidia’s journey from 1993 to today, focusing on:

The article is written for readers in tech, business, and investing who want a clear, narrative view of how Nvidia became an AI titan—and what might come next.

In 1993, three engineers with very different personalities but a shared conviction about 3D graphics started Nvidia around a Denny’s booth in Silicon Valley. Jensen Huang, a Taiwanese-American engineer and former chip designer at LSI Logic, brought big ambition and a talent for storytelling with customers and investors. Chris Malachowsky came from Sun Microsystems with deep experience in high-performance workstations. Curtis Priem, formerly at IBM and Sun, was the systems architect obsessed with how hardware and software fit together.

The Valley at that time revolved around workstations, minicomputers, and emerging PC makers. 3D graphics were powerful but expensive, mostly tied to Silicon Graphics (SGI) and other workstation vendors serving professionals in CAD, film, and scientific visualization.

Huang and his co-founders saw an opening: take that kind of visual computing power and push it into affordable consumer PCs. If millions of people could get high-quality 3D graphics for games and multimedia, the market would be far larger than the niche workstation world.

Nvidia’s founding idea was not generic semiconductors; it was accelerated graphics for the mass market. Instead of CPUs doing everything, a specialized graphics processor would handle the heavy math of rendering 3D scenes.

The team believed this required:

Huang raised early capital from venture firms like Sequoia, but money was never abundant. The first chip, NV1, was ambitious but misaligned with the emerging DirectX standard and the dominant gaming APIs. It sold poorly and nearly killed the company.

Nvidia survived by pivoting quickly to NV3 (RIVA 128), repositioning the architecture around industry standards and learning to work much more tightly with game developers and Microsoft. The lesson: technology alone was not enough; ecosystem alignment would determine survival.

From the start, Nvidia cultivated a culture where engineers carried disproportionate influence and time-to-market was treated as existential. Teams moved fast, iterated designs aggressively, and accepted that some bets would fail.

Cash constraints bred frugality: reused office furniture, long hours, and a bias toward hiring a small number of highly capable engineers instead of building large, hierarchical teams. That early culture—technical intensity, urgency, and careful spending—would later shape how Nvidia attacked much larger opportunities beyond PC graphics.

In the early to mid-1990s, PC graphics were basic and fragmented. Many games still relied on software rendering, with the CPU doing most of the work. Dedicated 2D accelerators existed for Windows, and early 3D add‑in cards like 3dfx’s Voodoo helped games, but there was no standard way to program 3D hardware. APIs like Direct3D and OpenGL were still maturing, and developers often had to target specific cards.

This was the environment Nvidia entered: fast‑moving, messy, and full of opportunity for any company that could combine performance with a clean programming model.

Nvidia’s first major product, the NV1, launched in 1995. It tried to do everything at once: 2D, 3D, audio, and even Sega Saturn gamepad support on a single card. Technically, it focused on quadratic surfaces instead of triangles, just as Microsoft and most of the industry were standardizing 3D APIs around triangle polygons.

The mismatch with DirectX and limited software support made NV1 a commercial disappointment. But it taught Nvidia two crucial lessons: follow the dominant API (DirectX), and focus sharply on 3D performance rather than exotic features.

Nvidia regrouped with the RIVA 128 in 1997. It embraced triangles and Direct3D, delivered strong 3D performance, and integrated 2D and 3D into a single card. Reviewers took notice, and OEMs began to see Nvidia as a serious partner.

RIVA TNT and TNT2 refined the formula: better image quality, higher resolutions, and improved drivers. While 3dfx still led in mindshare, Nvidia was closing the gap quickly by shipping frequent driver updates and courting game developers.

In 1999, Nvidia introduced GeForce 256 and branded it the “world’s first GPU” — a Graphics Processing Unit. This was more than marketing. GeForce 256 integrated hardware transform and lighting (T&L), offloading geometry calculations from the CPU to the graphics chip itself.

This shift freed CPUs for game logic and physics while the GPU handled increasingly complex 3D scenes. Games could draw more polygons, use more realistic lighting, and run smoother at higher resolutions.

At the same time, PC gaming was exploding, driven by titles like Quake III Arena and Unreal Tournament, and by the rapid adoption of Windows and DirectX. Nvidia aligned itself tightly with this growth.

The company secured design wins with major OEMs like Dell and Compaq, ensuring that millions of mainstream PCs shipped with Nvidia graphics by default. Joint marketing programs with game studios and the “The Way It’s Meant to Be Played” branding reinforced Nvidia’s image as the default choice for serious PC gamers.

By the early 2000s, Nvidia had transformed from a struggling startup with a misaligned first product into a dominant force in PC graphics, setting the stage for everything that would follow in GPU computing and, eventually, AI.

When Nvidia began, GPUs were mostly fixed‑function machines: hard‑wired pipelines that took vertices and textures in and spat pixels out. They were incredibly fast, but almost completely inflexible.

Around the early 2000s, programmable shaders (Vertex and Pixel/Fragment Shaders in DirectX and OpenGL) changed that formula. With chips like GeForce 3 and later GeForce FX and GeForce 6, Nvidia started exposing small programmable units that let developers write custom effects instead of relying on a rigid pipeline.

These shaders were still aimed at graphics, but they planted a crucial idea inside Nvidia: if a GPU could be programmed for many different visual effects, why couldn’t it be programmed for computation more broadly?

General‑purpose GPU computing (GPGPU) was a contrarian bet. Internally, many questioned whether it made sense to spend scarce transistor budget, engineering time, and software effort on workloads outside gaming. Externally, skeptics dismissed GPUs as toys for graphics, and early GPGPU experiments—hacking linear algebra into fragment shaders—were notoriously painful.

Nvidia’s answer was CUDA, announced in 2006: a C/C++‑like programming model, runtime, and toolchain designed to make the GPU feel like a massively parallel coprocessor. Instead of forcing scientists to think in terms of triangles and pixels, CUDA exposed threads, blocks, grids, and explicit memory hierarchies.

It was a huge strategic risk: Nvidia had to build compilers, debuggers, libraries, documentation, and training programs—software investments more typical of a platform company than a chip vendor.

The first wins came from high‑performance computing:

Researchers could suddenly run weeks‑long simulations in days or hours, often on a single GPU in a workstation instead of an entire CPU cluster.

CUDA did more than speed up code; it created a developer ecosystem around Nvidia hardware. The company invested in SDKs, math libraries (like cuBLAS and cuFFT), university programs, and its own conference (GTC) to teach parallel programming on GPUs.

Every CUDA application and library deepened the moat: developers optimized for Nvidia GPUs, toolchains matured around CUDA, and new projects started with Nvidia as the default accelerator. Long before AI training filled data centers with GPUs, this ecosystem had already turned programmability into one of Nvidia’s most powerful strategic assets.

By the mid‑2000s, Nvidia’s gaming business was thriving, but Jensen Huang and his team saw a limit to relying on consumer GPUs alone. The same parallel processing power that made games smoother could also accelerate scientific simulations, finance, and eventually AI.

Nvidia began positioning GPUs as general‑purpose accelerators for workstations and servers. Professional cards for designers and engineers (the Quadro line) were an early step, but the bigger bet was to move straight into the heart of the data center.

In 2007 Nvidia introduced the Tesla product line, its first GPUs built specifically for high‑performance computing (HPC) and server workloads rather than for displays.

Tesla boards emphasized double‑precision performance, error‑correcting memory, and power efficiency in dense racks—features data centers and supercomputing sites cared about far more than frame rates.

HPC and national labs became crucial early adopters. Systems like the “Titan” supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory showcased that clusters of CUDA‑programmable GPUs could deliver huge speedups for physics, climate modeling, and molecular dynamics. That credibility in HPC would later help convince enterprise and cloud buyers that GPUs were serious infrastructure, not just gaming gear.

Nvidia invested heavily in relationships with universities and research institutes, seeding labs with hardware and CUDA tools. Many of the researchers who experimented with GPU computing in academia later drove adoption inside companies and startups.

At the same time, early cloud providers started offering Nvidia‑powered instances, turning GPUs into an on‑demand resource. Amazon Web Services, followed by Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud, made Tesla‑class GPUs accessible to anyone with a credit card, which proved vital for deep learning on GPUs.

As the data center and professional markets grew, Nvidia’s revenue base broadened. Gaming remained a pillar, but new segments—HPC, enterprise AI, and cloud—evolved into a second engine of growth, laying the economic foundation for Nvidia’s later AI dominance.

The turning point came in 2012, when a neural network called AlexNet stunned the computer vision community by crushing the ImageNet benchmark. Crucially, it ran on a pair of Nvidia GPUs. What had been a niche idea—training giant neural networks with graphics chips—suddenly looked like the future of AI.

Deep neural networks are built from huge numbers of identical operations: matrix multiplies and convolutions applied across millions of weights and activations. GPUs were designed to run thousands of simple, parallel threads for graphics shading. That same parallelism fit neural networks almost perfectly.

Instead of rendering pixels, GPUs could process neurons. Compute-heavy, embarrassingly parallel workloads that would crawl on CPUs could now be accelerated by orders of magnitude. Training times that once took weeks dropped to days or hours, enabling researchers to iterate quickly and scale models up.

Nvidia moved fast to turn this research curiosity into a platform. CUDA had already given developers a way to program GPUs, but deep learning needed higher-level tools.

Nvidia built cuDNN, a GPU-optimized library for neural network primitives—convolutions, pooling, activation functions. Frameworks like Caffe, Theano, Torch, and later TensorFlow and PyTorch integrated cuDNN, so researchers could get GPU speedups without hand-tuning kernels.

At the same time, Nvidia tuned its hardware: adding mixed-precision support, high-bandwidth memory, and then Tensor Cores in the Volta and later architectures, specifically designed for matrix math in deep learning.

Nvidia cultivated close relationships with leading AI labs and researchers at places like the University of Toronto, Stanford, Google, Facebook, and early startups such as DeepMind. The company offered early hardware, engineering help, and custom drivers, and in return got direct feedback on what AI workloads needed next.

To make AI supercomputing more accessible, Nvidia introduced DGX systems—pre-integrated AI servers packed with high-end GPUs, fast interconnects, and tuned software. DGX-1 and its successors became the default appliance for many labs and enterprises building serious deep learning capabilities.

With GPUs such as the Tesla K80, P100, V100 and eventually the A100 and H100, Nvidia stopped being a “gaming company that also did compute” and became the default engine for training and serving cutting-edge deep learning models. The AlexNet moment had opened a new era, and Nvidia positioned itself squarely at its center.

Nvidia didn’t win AI by selling faster chips alone. It built an end‑to‑end platform that makes building, deploying, and scaling AI far easier on Nvidia hardware than anywhere else.

The foundation is CUDA, Nvidia’s parallel programming model introduced in 2006. CUDA lets developers treat the GPU as a general‑purpose accelerator, with familiar C/C++ and Python toolchains.

On top of CUDA, Nvidia layers specialized libraries and SDKs:

This stack means a researcher or engineer rarely writes low‑level GPU code; they call Nvidia libraries that are tuned for each new GPU generation.

Years of investment in CUDA tooling, documentation, and training created a powerful moat. Millions of lines of production code, academic projects, and open‑source frameworks are optimized for Nvidia GPUs.

Moving to a rival architecture often means rewriting kernels, revalidating models, and retraining engineers. That switching cost keeps developers, startups, and large enterprises anchored to Nvidia.

Nvidia works tightly with hyperscale clouds, providing HGX and DGX reference platforms, drivers, and tuned software stacks so customers can rent GPUs with minimal friction.

The Nvidia AI Enterprise suite, NGC software catalog, and pretrained models give enterprises a supported path from pilot to production, whether on‑premises or in the cloud.

Nvidia extends its platform into complete vertical solutions:

These vertical platforms bundle GPUs, SDKs, reference applications, and partner integrations, giving customers something very close to a turnkey solution.

By nurturing ISVs, cloud partners, research labs, and systems integrators around its software stack, Nvidia turned GPUs into the default hardware for AI.

Every new framework optimized for CUDA, every startup that ships on Nvidia, and every cloud AI service tuned for its GPUs strengthens a feedback loop: more software on Nvidia attracts more users, which justifies more investment, widening the gap with competitors.

Nvidia’s rise to AI dominance is as much about strategic bets beyond the GPU as it is about the chips themselves.

The 2019 acquisition of Mellanox was a turning point. Mellanox brought InfiniBand and high‑end Ethernet networking, plus expertise in low‑latency, high‑throughput interconnects.

Training large AI models depends on stitching together thousands of GPUs into a single logical computer. Without fast networking, those GPUs idle while waiting for data or gradients to sync.

Technologies like InfiniBand, RDMA, NVLink, and NVSwitch reduce communication overhead and make massive clusters scale efficiently. That is why Nvidia’s most valuable AI systems—DGX, HGX, and full data center reference designs—combine GPUs, CPUs, NICs, switches, and software into an integrated platform. Mellanox gave Nvidia critical control over that fabric.

In 2020 Nvidia announced a plan to acquire Arm, aiming to combine its AI acceleration expertise with a widely licensed CPU architecture used in phones, embedded devices, and increasingly servers.

Regulators in the US, UK, EU, and China raised strong antitrust concerns: Arm is a neutral IP supplier to many of Nvidia’s rivals, and consolidation threatened that neutrality. After prolonged scrutiny and industry pushback, Nvidia abandoned the deal in 2022.

Even without Arm, Nvidia moved ahead with its own Grace CPU, showing it still intends to shape the full data center node, not just the accelerator card.

Omniverse extends Nvidia into simulation, digital twins, and 3D collaboration. It connects tools and data around OpenUSD, letting enterprises simulate factories, cities, and robots before deploying in the physical world. Omniverse is both a heavy GPU workload and a software platform that locks in developers.

In automotive, Nvidia’s DRIVE platform targets centralized in‑car computing, autonomous driving, and advanced driver assistance. By providing hardware, SDKs, and validation tools to automakers and tier‑1 suppliers, Nvidia embeds itself in long product cycles and recurring software revenue.

At the edge, Jetson modules and related software stacks power robotics, smart cameras, and industrial AI. These products push Nvidia’s AI platform into retail, logistics, healthcare, and cities, capturing workloads that cannot live only in the cloud.

Through Mellanox and networking, failed but instructive plays like Arm, and expansions into Omniverse, automotive, and edge AI, Nvidia has deliberately moved beyond being a “GPU vendor.”

It now sells:

These bets make Nvidia harder to displace: competitors must match not just a chip, but a tightly integrated stack spanning compute, networking, software, and domain‑specific solutions.

Nvidia’s rise has drawn powerful rivals, tougher regulators, and new geopolitical risks that shape every strategic move the company makes.

AMD remains Nvidia’s closest peer in GPUs, often competing head‑to‑head on gaming and data center accelerators. AMD’s MI series AI chips target the same cloud and hyperscale customers Nvidia serves with its H100 and successor parts.

Intel attacks from several angles: x86 CPUs that still dominate servers, its own discrete GPUs, and custom AI accelerators. At the same time, hyperscalers like Google (TPU), Amazon (Trainium/Inferentia), and a wave of startups (e.g., Graphcore, Cerebras) design their own AI chips to reduce reliance on Nvidia.

Nvidia’s key defense remains a combination of performance leadership and software. CUDA, cuDNN, TensorRT, and a deep stack of SDKs, libraries, and AI frameworks lock in developers and enterprises. Hardware alone is not enough; porting models and tooling away from Nvidia’s ecosystem carries real switching costs.

Governments now treat advanced GPUs as strategic assets. U.S. export controls have repeatedly tightened limits on shipping high‑end AI chips to China and other sensitive markets, forcing Nvidia to design “export‑compliant” variants with capped performance. These controls protect national security but constrain access to a major growth region.

Regulators are also watching Nvidia’s market power. The blocked Arm acquisition highlighted concerns about allowing Nvidia to control foundational chip IP. As Nvidia’s share of AI accelerators grows, regulators in the U.S., EU, and elsewhere are more willing to examine exclusivity, bundling, and potential discrimination in access to hardware and software.

Nvidia is a fabless company, heavily dependent on TSMC for leading‑edge manufacturing. Any disruption in Taiwan—whether from natural disasters, political tension, or conflict—would directly hit Nvidia’s ability to supply top‑tier GPUs.

Global shortages of advanced packaging capacity (CoWoS, HBM integration) already create supply bottlenecks, giving Nvidia less flexibility to respond to surging demand. The company must negotiate capacity, navigate U.S.–China technology frictions, and hedge against export rules that can change faster than semiconductor roadmaps.

Balancing these pressures while sustaining its technology lead is now as much a geopolitical and regulatory task as it is an engineering challenge.

Jensen Huang is a founder-CEO who still behaves like a hands-on engineer. He is deeply involved in product strategy, spending time in technical reviews and whiteboard sessions, not just earnings calls.

His public persona blends showmanship and clarity. The leather jacket presentations are deliberate: he uses simple metaphors to explain complex architectures, positioning Nvidia as a company that understands both physics and business. Internally, he is known for direct feedback, high expectations, and a willingness to make uncomfortable decisions when technology or markets shift.

Nvidia’s culture is built around a few recurring themes:

This mix creates a culture where long feedback loops (chip design) coexist with rapid loops (software and research), and where hardware, software, and research groups are expected to collaborate tightly.

Nvidia routinely invests in multi-year platforms—new GPU architectures, networking, CUDA, AI frameworks—while still managing quarterly expectations.

Organizationally, this means:

Huang often frames earnings discussions around long-term secular trends (AI, accelerated computing) to keep investors aligned with the company’s time horizon, even when near-term demand swings.

Nvidia treats developers as a primary customer. CUDA, cuDNN, TensorRT, and dozens of domain SDKs are backed by:

Partner ecosystems—OEMs, cloud providers, system integrators—are cultivated with reference designs, joint marketing, and early access to roadmaps. This tight ecosystem makes Nvidia’s platform sticky and hard to displace.

As Nvidia grew from a graphics card vendor into a global AI platform company, its culture evolved:

Despite this scale, Nvidia has tried to preserve a founder-led, engineering-first mentality, where ambitious technical bets are encouraged and teams are expected to move quickly in pursuit of breakthroughs.

Nvidia’s financial arc is one of the most dramatic in technology: from a scrappy PC graphics supplier to a multi‑trillion‑dollar company at the center of the AI boom.

After its 1999 IPO, Nvidia spent years valued in the single‑digit billions, tied largely to the cyclical PC and gaming markets. Through the 2000s, revenue grew steadily into the low billions, but the company was still seen as a specialist chip vendor, not a platform leader.

The inflection came in the mid‑2010s as data center and AI revenue began to compound. By around 2017 Nvidia’s market cap crossed the $100 billion mark; by 2021 it was one of the most valuable semiconductor companies in the world. In 2023 it briefly joined the trillion‑dollar club, and by 2024 it was often trading well above that level, reflecting investor conviction that Nvidia is a foundational AI infrastructure provider.

For much of its history, gaming GPUs were the core business. Consumer graphics, plus professional visualization and workstation cards, drove the bulk of revenue and profits.

That mix flipped with the explosion of AI and accelerated computing in the cloud:

The economics of AI hardware have transformed Nvidia’s financial profile. High‑end accelerator platforms, plus networking and software, carry premium pricing and high gross margins. As data center revenue surged, overall margins expanded, turning Nvidia into a cash machine with extraordinary operating leverage.

AI demand did not just add another product line; it redefined how investors value Nvidia. The company shifted from being modeled as a cyclical semiconductor name to being treated more like a critical infrastructure and software platform.

Gross margins, supported by AI accelerators and platform software, moved solidly into the 70%+ range. With fixed costs scaling far more slowly than revenue, incremental margins on AI growth have been extremely high, driving explosive earnings per share. This profit acceleration triggered multiple waves of upward revisions from analysts and repricing in the stock.

The result has been a series of powerful re‑rating cycles: Nvidia’s valuation expanded from typical chipmaker multiples to premium levels more comparable to top cloud and software platforms, reflecting expectations of durable AI demand.

Nvidia’s share price history is punctuated by both spectacular rallies and sharp drawdowns.

The company has split its stock multiple times to keep per‑share prices accessible: several 2‑for‑1 splits in the early 2000s, a 4‑for‑1 split in 2021, and a 10‑for‑1 split in 2024. Long‑term shareholders who held through these events have seen extraordinary compounded returns.

Volatility has been just as notable. The stock has suffered deep pullbacks during:

Each time, concerns about cyclicality or demand corrections hit the shares hard. Yet the subsequent AI boom has repeatedly pulled Nvidia to new highs as consensus expectations reset.

Despite its success, Nvidia is not seen as risk‑free. Investors debate several key issues:

At the same time, the long‑term bull case is that accelerated computing and AI become standard across data centers, enterprises, and edge devices for decades. In that view, Nvidia’s combination of GPUs, networking, software, and ecosystem lock‑in could justify years of high growth and strong margins, supporting the transition from niche chipmaker to enduring market giant.

Nvidia’s next chapter is about turning GPUs from a tool for training models into the underlying fabric of intelligent systems: generative AI, autonomous machines, and simulated worlds.

Generative AI is the immediate focus. Nvidia wants every major model—text, image, video, code—to be trained, fine‑tuned, and served on its platform. That means more powerful data center GPUs, faster networking, and software stacks that make it easy for enterprises to build custom copilots and domain‑specific models.

Beyond the cloud, Nvidia is pushing autonomous systems: self‑driving cars, delivery robots, factory arms, and drones. The goal is to reuse the same CUDA, AI, and simulation stack across automotive (Drive), robotics (Isaac), and embedded platforms (Jetson).

Digital twins tie this together. With Omniverse and related tools, Nvidia is betting that companies will simulate factories, cities, 5G networks—even power grids—before they build or reconfigure them. That creates long‑lived software and service revenue on top of hardware.

Automotive, industrial automation, and edge computing are huge prizes. Cars are turning into rolling data centers, factories into AI‑driven systems, and hospitals and retail spaces into sensor‑rich environments. Each needs low‑latency inference, safety‑critical software, and strong developer ecosystems—areas where Nvidia is investing heavily.

But the risks are real:

For founders and engineers, Nvidia’s history shows the power of owning a full stack: hardware, system software, and developer tools, while continuously betting on the next compute bottleneck before it’s obvious.

For policymakers, it’s a case study in how critical computing platforms become strategic infrastructure. Choices on export controls, competition policy, and funding for open alternatives will shape whether Nvidia remains the dominant gateway to AI, or one important player in a more diverse ecosystem.

Nvidia was founded around a very specific bet: that 3D graphics would move from expensive workstations into mass‑market PCs, and that this shift would need a dedicated graphics processor tightly coupled with software.

Instead of trying to be a general semiconductor company, Nvidia:

This narrow but deep focus on one problem—real‑time graphics—created the technical and cultural base that later translated into GPU computing and AI acceleration.

CUDA turned Nvidia’s GPUs from fixed‑function graphics hardware into a general‑purpose parallel computing platform.

Key ways it enabled AI dominance:

Mellanox gave Nvidia control over the networking fabric that connects thousands of GPUs in AI supercomputers.

For large models, performance depends not just on fast chips but on how quickly they can exchange data and gradients. Mellanox brought:

Nvidia’s revenue has shifted from being gaming‑heavy to data‑center‑dominant.

At a high level:

Nvidia faces pressure from both traditional rivals and custom accelerators:

Advanced GPUs are now treated as strategic technology, especially for AI.

Impacts on Nvidia include:

Nvidia’s AI stack is a layered set of tools that hide GPU complexity from most developers:

Autonomous driving and robotics are extensions of Nvidia’s core AI and simulation platform into physical systems.

Strategically, they:

Nvidia’s trajectory offers several lessons:

If future workloads move away from GPU‑friendly patterns, Nvidia would need to adapt its hardware and software quickly.

Possible shifts include:

Nvidia’s likely response would be to:

By the time deep learning took off, the tools, docs, and habits around CUDA were already mature, giving Nvidia a huge head start.

This let Nvidia sell integrated platforms (DGX, HGX, full data center designs) where GPUs, networking, and software are co‑optimized, instead of just selling standalone accelerator cards.

High‑end AI platforms and networking carry premium prices and margins, which is why data center growth has transformed Nvidia’s overall profitability.

Nvidia’s main defenses are performance leadership, CUDA/software lock‑in, and integrated systems. But if alternatives become “good enough” and easier to program, its share and pricing power could be pressured.

As a result, Nvidia’s strategy must account not only for engineering and markets but also for policy, trade rules, and regional industrial plans.

Most teams call these libraries through frameworks like PyTorch or TensorFlow, so they rarely write low‑level GPU code directly.

These markets may be smaller than cloud AI today but can generate durable, high‑margin revenue and deepen Nvidia’s ecosystem across industries.

For builders, the takeaway is to pair deep technical insight with ecosystem thinking, not just focus on raw performance.

Its history suggests it can pivot, but such shifts would test how adaptable the company really is.