Aug 27, 2025·7 min

Go worker pools for background jobs: retries, cancel, shutdown

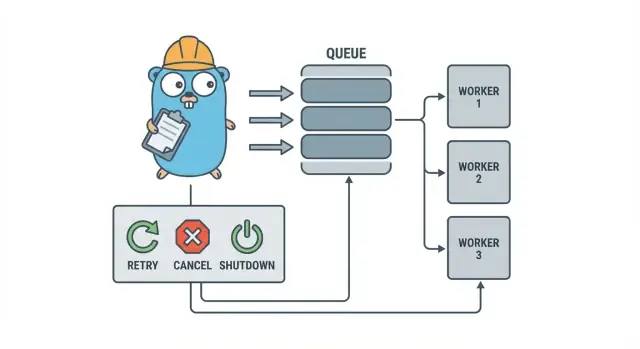

Go worker pools help small teams run background jobs with retries, cancellation, and clean shutdown using simple patterns before adding heavy infrastructure.

Why background jobs get messy fast

In a small Go service, background work usually starts with a simple goal: return the HTTP response quickly, then do the slow stuff after. That might be sending emails, resizing images, syncing to another API, rebuilding search indexes, or running nightly reports.

The problem is that these jobs are real production work, just without the guardrails you naturally get in request handling. A goroutine kicked off from an HTTP handler feels fine until a deploy happens mid-task, an upstream API slows down, or the same request is retried and triggers the job twice.

The first pain points are predictable:

- Stuck jobs: one call hangs, and workers stop making progress.

- Duplicate work: retries at the HTTP layer re-run the same job.

- No shutdown plan: the process exits and work is lost or half-done.

- Silent failures: errors get logged once (or not at all) and disappear.

- Retry storms: failing jobs retry instantly and overload dependencies.

This is where a small, explicit pattern like a Go worker pool helps. It makes concurrency a choice (N workers), turns “do this later” into a clear job type, and gives you one place to handle retries, timeouts, and cancellation.

Example: a SaaS app needs to send invoices. You don’t want 500 simultaneous sends after a batch import, and you don’t want to resend the same invoice because a request was retried. A worker pool lets you cap throughput and treat “send invoice #123” as a tracked unit of work.

A worker pool isn’t the right tool when you need durable, cross-process guarantees. If jobs must survive crashes, be scheduled for the future, or be processed by multiple services, you’ll likely need a real queue plus persistent storage for job state.

The worker pool model in plain language

A Go worker pool is deliberately boring: put work into a queue, have a fixed set of workers pull from it, and make sure the whole thing can stop cleanly.

The basic terms:

- Job: one unit of work, like “resize this image” or “send this invoice email”.

- Queue: where jobs wait.

- Worker: a goroutine that repeatedly takes a job and runs it.

- Dispatcher: the part that accepts jobs and feeds them into the queue.

In many in-process designs, a Go channel is the queue. A buffered channel can hold a limited number of jobs before producers block. That blocking is backpressure, and it’s often what keeps your service from accepting unlimited work and running out of memory when traffic spikes.

Buffer size changes the feel of the system. A small buffer makes pressure visible quickly (callers wait sooner). A larger buffer smooths short bursts but can hide overload until later. There’s no perfect number, only a number that matches how much waiting you can tolerate.

You also choose whether the pool size is fixed or can change. Fixed pools are easier to reason about and keep resource use predictable. Auto-scaling workers can help with uneven load, but adds decisions you’ll have to maintain (when to scale, by how much, and when to scale back).

Finally, “ack” in an in-process pool usually just means “the worker finished the job and returned no error.” There’s no external broker to confirm delivery, so your code defines what “done” means and what happens when a job fails or gets canceled.

Design goals: retries, cancellation, and clean shutdown

A worker pool is simple mechanically: run a fixed number of workers, feed them jobs, and process them. The value is control: predictable concurrency, clear failure handling, and a shutdown path that doesn’t leave half-finished work behind.

Three goals keep small teams sane:

- Limit concurrency so one spike doesn’t melt the database or an external API.

- Avoid losing work (or at least know exactly what was dropped and why).

- Stay debuggable: every job should be traceable through logs and a few counters.

Most failures are boring, but you still want to treat them differently:

- Transient errors (network hiccups, rate limits) that should be retried.

- Permanent errors (bad input, missing record) that should not be retried.

- Timeouts (a dependency hangs) that must be cut off so workers don’t clog.

Cancellation isn’t the same as “error.” It’s a decision: a user canceled, a deploy replaced your process, or your service is shutting down. In Go, treat cancellation as a first-class signal using context cancellation, and make sure each job checks it before starting expensive work and at a few safe points during execution.

Clean shutdown is where many pools fall apart. Decide early what “safe” means for your jobs: do you finish in-flight work, or do you stop quickly and re-run later? A practical flow is:

- Stop accepting new jobs.

- Tell workers to stop after their current job (or stop immediately).

- Wait up to a deadline, then force exit.

If you define these rules early, retries, cancellation, and shutdown stay small and predictable instead of turning into a homegrown framework.

Step by step: build a basic worker pool

A worker pool is just a group of goroutines pulling jobs from a channel and doing work. The important part is making the basics predictable: what a job looks like, how workers stop, and how you know when all work is finished.

Start with a simple Job type. Give it an ID (for logs), a payload (what to process), an attempt counter (useful later for retries), timestamps, and a place to store per-job context data.

package jobs

import (

"context"

"sync"

"time"

)

type Job struct {

ID string

Payload any

Attempt int

Enqueued time.Time

Started time.Time

Ctx context.Context

Meta map[string]string

}

type Pool struct {

ctx context.Context

cancel context.CancelFunc

jobs chan Job

wg sync.WaitGroup

}

func New(size, queue int) *Pool {

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

p := 6Pool{ctx: ctx, cancel: cancel, jobs: make(chan Job, queue)}

for i := 0; i c size; i++ {

go p.worker(i)

}

return p

}

func (p *Pool) worker(_ int) {

for {

select {

case c-p.ctx.Done():

return

case job, ok := c-p.jobs:

if !ok {

return

}

p.wg.Add(1)

job.Started = time.Now()

_ = job // call your handler here

p.wg.Done()

}

}

}

// Submit blocks when the queue is full (backpressure).

func (p *Pool) Submit(job Job) error {

if job.Enqueued.IsZero() {

job.Enqueued = time.Now()

}

select {

case c-p.ctx.Done():

return context.Canceled

case p.jobs c- job:

return nil

}

}

func (p *Pool) Stop() { p.cancel() }

func (p *Pool) Wait() { p.wg.Wait() }

A few practical choices you’ll make right away:

- Pick a queue size based on how much waiting you can tolerate.

- Decide what backpressure means for callers: block, return an error, or drop.

- Keep

Stop()andWait()separate so you can stop intake first, then wait for in-flight work to finish.

Adding retries without turning it into a framework

Retries are useful, but they’re also where worker pools get messy. Keep the goal narrow: retry only when another attempt has a real chance to succeed, and stop quickly when it doesn’t.

Start by deciding what’s retryable. Temporary problems (network hiccups, timeouts, “try again later” responses) are usually worth retrying. Permanent ones (bad input, missing records, permission denied) are not.

A small retry policy is usually enough:

- Mark errors as retryable vs not retryable (for example, wrap them with a

Retryable(err)helper). - Set a max attempt count (often 3 to 5). Beyond that, you’re usually just burning time.

- Use exponential backoff with jitter so jobs don’t retry in sync.

- Cap the delay (for example, never sleep more than 30 seconds).

- Log retries with attempt number, next delay, and job ID.

Backoff doesn’t need to be complicated. A common shape is: delay = min(base * 2^(attempt-1), max), then add jitter (randomize by +/- 20%). Jitter matters because otherwise many workers fail together and retry together.

Where should the delay live? For small systems, sleeping inside the worker is fine, but it ties up a worker slot. If retries are rare, that’s acceptable. If retries are common or delays are long, consider re-enqueuing the job with a “run after” timestamp so workers stay busy on other work.

On the final failure, be explicit. Store the failed job (and last error) for review, log enough context to replay it, or push it into a dead list you check regularly. Avoid silent drops. A pool that hides failures is worse than having no retries.

Cancellation and timeouts that actually stop work

Build clean shutdown in Go

Create signal handling and context timeouts in minutes from a chat prompt.

Worker pools only feel safe when you can stop them. The simplest rule is: pass a context.Context through every layer that can block. That means submission, execution, and cleanup.

A practical setup uses two time limits:

- A per-job timeout so one task can’t hog a worker forever.

- A shutdown timeout so the process can exit even if some jobs won’t cooperate.

Use context end to end

Give each job its own context derived from the worker’s context. Then every slow call (database, HTTP, queues, file I/O) must use that context so it can return early.

func worker(ctx context.Context, jobs c-chan Job) {

for {

select {

case c-ctx.Done():

return

case job, ok := c-jobs:

if !ok { return }

jobCtx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(ctx, job.Timeout)

_ = job.Run(jobCtx) // Run must respect jobCtx

cancel()

}

}

}

If Run calls your DB or an API, wire the context into those calls (for example, QueryContext, NewRequestWithContext, or client methods that accept context). If you ignore it in one place, cancellation becomes “best effort” and usually fails when you need it most.

Partial work and “safe to retry” steps

Cancellation can happen mid-job, so assume partial work is normal. Aim for idempotent steps so reruns don’t create duplicates. Common approaches include using unique keys for inserts (or upserts), writing progress markers (started/done), storing results before continuing, and checking ctx.Err() between steps.

Treat shutdown like a deadline: stop accepting new jobs, cancel worker contexts, and wait only up to the shutdown timeout for in-flight jobs to exit.

Clean shutdown: what to do when the process must exit

A clean shutdown has one job: stop taking new work, tell in-flight work to stop, and exit without leaving the system in a weird state.

Start with signals. In most deployments you’ll see SIGINT locally and SIGTERM from your process manager or container runtime. Use a shutdown context that’s canceled when a signal arrives, and pass it into your pool and job handlers.

Next, stop accepting new jobs. Don’t let callers block forever trying to submit to a channel nobody reads anymore. Keep submissions behind a single function that checks a closed flag or selects on the shutdown context before sending.

Then decide what happens to queued work:

- Drain: finish what’s already queued, but reject new submissions.

- Drop: discard anything not yet started.

Draining is safer for things like payments and emails. Dropping is fine for “nice to have” tasks like recomputing a cache.

A practical shutdown sequence:

- Catch SIGINT/SIGTERM and cancel a shared context.

- Stop submissions (close the submit path, not necessarily the work channel).

- Let workers finish or abort based on context.

- Wait for workers with a WaitGroup.

- Enforce a deadline, then exit.

The deadline matters. For example, give in-flight jobs 10 seconds to stop. After that, log what’s still running and exit. That keeps deploys predictable and avoids stuck processes.

Logging and simple metrics for worker pools

Deploy your background worker

Deploy your Go app with hosting support when you are ready to run it.

When a worker pool breaks, it rarely fails loudly. Jobs slow down, retries pile up, and someone reports that “nothing is happening.” Logging and a few basic counters turn that into a clear story.

Give every job a stable ID (or generate one at submit time) and include it in every log line. Keep logs consistent: one line when a job starts, one when it finishes, and one when it fails. If you retry, log the attempt number and the next delay.

A simple log shape:

- start: job_id, worker_id, attempt, kind

- finish: job_id, worker_id, attempt, duration_ms

- fail/retry: job_id, worker_id, attempt, err, next_delay_ms

Metrics can stay minimal and still pay off. Track queue length, in-flight jobs, total success and failures, and job latency (at least average and max). If queue length keeps climbing and in-flight stays pegged at the worker count, you’re saturated. If submitters block sending into the jobs channel, backpressure is reaching the caller. That’s not always bad, but it should be deliberate.

When “jobs are stuck,” check whether the process is still receiving jobs, whether queue length is growing, whether workers are alive, and which jobs have been running the longest. Long runtimes usually point to missing timeouts, slow dependencies, or a retry loop that never stops.

A realistic example: a small SaaS background queue

Imagine a small SaaS where an order changes to PAID. Right after payment, you need to send an invoice PDF, email the customer, and notify your internal team. You don’t want that work blocking the web request. This is a good fit for a worker pool because the work is real, but the system is still small.

The job payload can be minimal: just enough to fetch the rest from your database. The API handler writes a row like jobs(status='queued', type='send_invoice', payload, attempts=0) in the same transaction as the order update, then a background loop polls for queued jobs and pushes them into the worker channel.

type SendInvoiceJob struct {

OrderID string

CustomerID string

Email string

}

When a worker picks it up, the happy path is straightforward: load the order, generate the invoice, call the email provider, then mark the job as done.

Retries are where this gets real. If your email provider has a temporary outage, you don’t want 1,000 jobs to fail forever or hammer the provider every second. A practical approach is:

- Treat network errors and 5xx responses as retryable.

- Use exponential backoff with a max delay (for example, 5s, 15s, 45s, 2m).

- Cap attempts (for example, 10) and then mark the job as failed.

- Record the last error so support can see what happened.

During the outage, jobs move from queued to in_progress, then back to queued with a future run time. Once the provider recovers, workers naturally drain the backlog.

Now picture a deploy. You send SIGTERM. The process should stop taking new work but finish what’s already in flight. Stop polling, stop feeding the worker channel, and wait for workers with a deadline. Jobs that finish get marked done. Jobs that are still running when the deadline hits should be marked back to queued (or left in progress with a watchdog) so they can be picked up after the new version starts.

Common mistakes and traps

Most bugs in background processing aren’t in the job logic. They come from coordination mistakes that only show up under load or during shutdown.

One classic trap is closing a channel from more than one place. The result is a panic that’s hard to reproduce. Pick one owner for each channel (usually the producer), and make it the only place that calls close(jobs).

Retries are another area where good intentions cause outages. If you retry everything, you’ll retry permanent failures too. That wastes time, increases load, and can turn a small issue into an incident. Classify errors and cap retries with a clear policy.

Duplicates will happen even with a careful design. Workers can crash mid-job, a timeout can fire after work finished, or you can requeue during deployment. If the job isn’t idempotent, duplicates become real damage: two invoices, two welcome emails, two refunds.

The mistakes that show up most often:

- Closing the same channel from multiple goroutines.

- Retrying permanent failures instead of surfacing them.

- No idempotency key, so duplicates cause double side effects.

- Unbounded in-memory queues that grow until memory spikes.

- Ignoring

context.Context, so work continues after shutdown starts.

Unbounded queues are especially sneaky. A spike in work can quietly pile up in RAM. Prefer a bounded channel buffer and decide what happens when it fills: block, drop, or return an error.

Quick checklist before shipping

Add logging and basic metrics

Generate logs and a few counters to track queue depth, latency, and failures.

Before you ship a worker pool to production, you should be able to describe the job lifecycle out loud. If someone asks “where is this job right now?”, the answer shouldn’t be a guess.

A practical pre-flight checklist:

- You can name each state and transition: queued, picked up, running, finished, failed (and what moves it between states).

- Concurrency is a single knob (like

workerCount), and changing it doesn’t require rewriting the code. - Retries are bounded: max attempts are clear, backoff grows, and permanent failure goes somewhere intentional.

- Shutdown behavior is proven: you stop intake, let in-flight jobs finish, and still have a hard timeout.

- Logs answer the basics: job ID, attempt number, duration, and the error reason.

Do one realistic drill before release: enqueue 100 “send receipt email” jobs, force 20 to fail, then restart the service mid-run. You should see retries behave as expected, no duplicate side effects, and cancellation actually stopping work when the deadline is reached.

If any item is fuzzy, tighten it now. Small fixes here save days later.

Next steps: when to add heavier infrastructure (and when not to)

A simple in-process pool is often enough while a product is young. If your jobs are “nice to have” (send emails, refresh caches, generate reports) and you can re-run them, a worker pool keeps the system easy to reason about.

Signs you’ve outgrown an in-process pool

Watch for these pressure points:

- You run multiple app instances and need only one of them to pick a job.

- You need durability (jobs must survive crashes and deploys).

- You need an audit trail: who queued what, when it ran, and the exact outcome.

- You need backpressure controls across services, not just inside one process.

- You need strict scheduling or long delays (hours or days) with reliable wake-up.

If none of those are true, heavier tools can add more moving parts than value.

Migrate gradually without a rewrite

The best hedge is a stable job interface: a small payload type, an ID, and a handler that returns a clear result. Then you can swap the queue backend later (from an in-memory channel to a database table, and only then to a dedicated queue) without changing business code.

A practical middle step is a small Go service that reads jobs from PostgreSQL, claims them with a lock, and updates status. You get durability and basic auditability while keeping the same worker logic.

If you want to prototype quickly, Koder.ai (koder.ai) can generate a Go + PostgreSQL starter from a chat prompt, including a background jobs table and a worker loop, and its snapshots and rollback can help while you tune retries and shutdown behavior.