Jan 04, 2026·6 min

Go context timeouts: a practical recipe for fast APIs

Go context timeouts keep slow DB calls and external requests from piling up. Learn deadline propagation, cancellation, and safe defaults.

Go context timeouts keep slow DB calls and external requests from piling up. Learn deadline propagation, cancellation, and safe defaults.

A single slow request is rarely "just slow." While it waits, it keeps a goroutine alive, holds memory for buffers and response objects, and often occupies a database connection or a slot in a pool. When enough slow requests pile up, your API stops doing useful work because its limited resources are stuck waiting.

You usually feel it in three places. Goroutines accumulate and scheduling overhead rises, so latency gets worse for everyone. Database pools run out of free connections, so even fast queries start queueing behind slow ones. Memory climbs from in-flight data and partially built responses, which increases GC work.

Adding more servers often doesn't fix it. If each instance hits the same bottleneck (a small DB pool, one slow upstream, shared rate limits), you just move the queue around and pay more while errors still spike.

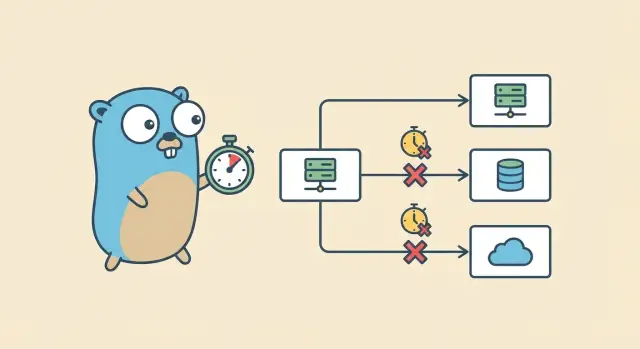

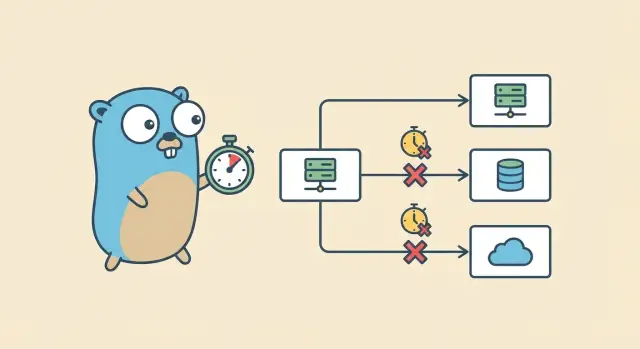

Picture a handler that fans out: it loads a user from PostgreSQL, calls a payments service, then calls a recommendation service. If the recommendation call hangs and nothing cancels it, the request never finishes. The DB connection might get returned, but the goroutine and HTTP client resources stay tied up. Multiply that by hundreds of requests and you get a slow meltdown.

The goal is simple: set a clear time limit, stop work when time is up, free resources, and return a predictable error. Go context timeouts give every step a deadline so work stops when the user is no longer waiting.

A context.Context is a small object you pass down your call chain so every layer agrees on one thing: when this request must stop. Timeouts are the common way to prevent one slow dependency from tying up your server.

A context can carry three kinds of information: a deadline (when work must stop), a cancellation signal (someone decided to stop early), and a few request-scoped values (use this sparingly, and never for big data).

Cancellation isn't magic. A context exposes a Done() channel. When it closes, the request is canceled or its time is up. Code that respects context checks Done() (often with a select) and returns early. You can also check ctx.Err() to learn why it ended, usually context.Canceled or context.DeadlineExceeded.

Use context.WithTimeout for "stop after X seconds." Use context.WithDeadline when you already know the exact cutoff time. Use context.WithCancel when a parent condition should stop the work (client disconnected, user navigated away, you already have the answer).

When a context is canceled, the correct behavior is boring but important: stop doing work, stop waiting on slow I/O, and return a clear error. If a handler is waiting on a database query and the context ends, return quickly and let the database call abort if it supports context.

The safest place to stop slow requests is the boundary where traffic enters your service. If a request is going to time out, you want it to happen predictably and early, not after it has tied up goroutines, DB connections, and memory.

Start at the edge (load balancer, API gateway, reverse proxy) and set a hard cap for how long any request is allowed to live. That protects your Go service even if a handler forgets to set a timeout.

Inside your Go server, set HTTP timeouts so the server doesn't wait forever for a slow client or a stalled response. At a minimum, configure timeouts for reading headers, reading the full request body, writing the response, and keeping idle connections alive.

Pick a default request budget that matches your product. For many APIs, 1 to 3 seconds is a reasonable starting point for typical requests, with a higher limit for known slow operations like exports. The exact number matters less than being consistent, measuring it, and having a clear rule for exceptions.

Streaming responses need extra care. It's easy to create an accidental infinite stream where the server keeps the connection open and writes tiny chunks forever, or waits forever before the first byte. Decide upfront whether an endpoint is truly a stream. If it isn't, enforce a maximum total time and a maximum time-to-first-byte.

Once the boundary has a clear deadline, it's much easier to propagate that deadline through the whole request.

The simplest place to start is the HTTP handler. It's where one request enters your system, so it's a natural place to set a hard limit.

Create a new context with a deadline, and make sure you cancel it. Then pass that context to anything that might block: database work, HTTP calls, or slow computations.

func (s *Server) GetUser(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(r.Context(), 2*time.Second)

defer cancel()

userID := r.URL.Query().Get("id")

if userID == "" {

http.Error(w, "missing id", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

user, err := s.loadUser(ctx, userID)

if err != nil {

writeError(w, ctx, err)

return

}

writeJSON(w, http.StatusOK, user)

}

A good rule: if a function can wait on I/O, it should accept a context.Context. Keep handlers readable by pushing details into small helper functions like loadUser.

func (s *Server) loadUser(ctx context.Context, id string) (User, error) {

return s.repo.GetUser(ctx, id) // repo should use QueryRowContext/ExecContext

}

If the deadline is hit (or the client disconnects), stop work and return a user-friendly response. A common mapping is context.DeadlineExceeded to 504 Gateway Timeout, and context.Canceled to "client is gone" (often no response body).

func writeError(w http.ResponseWriter, ctx context.Context, err error) {

if errors.Is(err, context.DeadlineExceeded) {

http.Error(w, "request timed out", http.StatusGatewayTimeout)

return

}

if errors.Is(err, context.Canceled) {

// Client went away. Avoid doing more work.

return

}

http.Error(w, "internal error", http.StatusInternalServerError)

}

This pattern prevents pile-ups. Once the timer expires, every context-aware function down the chain gets the same stop signal and can exit quickly.

Once your handler has a context with a deadline, the most important rule is simple: use that same ctx all the way into the database call. That's how timeouts stop work instead of only stopping your handler from waiting.

With database/sql, prefer the context-aware methods:

func (s *Server) getUser(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ctx := r.Context()

row := s.db.QueryRowContext(ctx,

"SELECT id, email FROM users WHERE id = $1",

r.URL.Query().Get("id"),

)

var id int64

var email string

if err := row.Scan(&id, &email); err != nil {

// handle below

}

}

If the handler budget is 2 seconds, the database should get only a slice of that. Leave time for JSON encoding, other dependencies, and error handling. A simple starting point is to give Postgres 30% to 60% of the total budget. With a 2 second handler deadline, that might be 800ms to 1.2s.

When the context is canceled, the driver asks Postgres to stop the query. Usually the connection returns to the pool and can be reused. If cancellation happens during a bad network moment, the driver may discard that connection and open a new one later. Either way, you avoid a goroutine waiting forever.

When checking errors, treat timeouts differently from real DB failures. If errors.Is(err, context.DeadlineExceeded), you ran out of time and should return a timeout. If errors.Is(err, context.Canceled), the client went away and you should stop quietly. Other errors are normal query problems (bad SQL, missing row, permissions).

If your handler has a deadline, your outbound HTTP calls should respect it too. Otherwise the client gives up, but your server keeps waiting on a slow upstream and ties up goroutines, sockets, and memory.

Build outbound requests with the parent context so cancellation travels automatically:

func fetchUser(ctx context.Context, url string) ([]byte, error) {

// Add a small per-call cap, but never exceed the parent deadline.

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 800*time.Millisecond)

defer cancel()

req, err := http.NewRequestWithContext(ctx, http.MethodGet, url, nil)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

resp, err := http.DefaultClient.Do(req)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

defer resp.Body.Close() // always close, even on non-200

return io.ReadAll(resp.Body)

}

That per-call timeout is a safety net. The parent request deadline is still the real boss. One clock for the whole request, plus smaller caps for risky steps.

Also set timeouts at the transport level. Context cancels the request, but transport timeouts protect you from slow handshakes and servers that never send headers.

One detail that bites teams: response bodies must be closed on every path. If you return early (status code check, JSON decode error, context timeout), still close the body. Leaking bodies can quietly exhaust connections in the pool and turn into "random" latency spikes.

A concrete scenario: your API calls a payment provider. The client times out after 2 seconds, but the upstream hangs for 30 seconds. Without request cancellation and transport timeouts, you keep paying for that 30 second wait for every abandoned request.

A single request usually touches more than one slow thing: handler work, a database query, and one or more external APIs. If you give each step a generous timeout, the total time quietly grows until users feel it and your server piles up.

Budgeting is the simplest fix. Set one parent deadline for the whole request, then give each dependency a smaller slice. Child deadlines should be earlier than the parent so you fail fast and still have time to return a clean error.

Rules of thumb that hold up in real services:

Avoid stacking timeouts that fight each other. If your handler context has a 2 second deadline and your HTTP client has a 10 second timeout, you're safe but it's confusing. If it's the other way around, the client may cut off early for unrelated reasons.

For background work (audit logs, metrics, emails), don't reuse the request context. Use a separate context with its own short timeout so client cancellations don't kill important cleanup.

Most timeout bugs aren't in the handler. They happen one or two layers down, where the deadline quietly gets lost. If you set timeouts at the edge but ignore them in the middle, you can still end up with goroutines, DB queries, or HTTP calls that keep running after the client has gone.

The patterns that show up most often are simple:

context.Background() (or TODO). That disconnects work from the client cancel and the handler deadline.ctx.Done(). The request is canceled, but your code keeps waiting.context.WithTimeout. You end up with many timers and confusing deadlines.ctx to blocking calls (DB queries, outbound HTTP, message publishes). A handler timeout does nothing if the dependency call ignores it.A classic failure: you add a 2 second timeout in the handler, then your repository uses context.Background() for the database query. Under load, a slow query continues running even after the client gave up, and the pile grows.

Fix the basics: pass ctx as a first argument through your call stack. Inside long work, add quick checks like select { case <-ctx.Done(): return ctx.Err() default: }. Map context.DeadlineExceeded to a timeout response (often 504) and context.Canceled to a client-cancel style response (often 408 or 499 depending on your conventions).

Timeouts only help if you can see them happen and confirm the system recovers cleanly. When something is slow, the request should stop, resources should be released, and the API should stay responsive.

For every request, log the same small set of fields so you can compare normal requests vs timeouts. Include the context deadline (if it exists) and what ended the work.

Useful fields include the deadline (or "none"), total elapsed time, cancellation reason (timeout vs client canceled), a short operation label ("db.query users", "http.call billing"), and a request ID.

A minimal pattern looks like this:

start := time.Now()

deadline, hasDeadline := ctx.Deadline()

err := doWork(ctx)

log.Printf("op=%s hasDeadline=%t deadline=%s elapsed=%s err=%v",

"getUser", hasDeadline, deadline.Format(time.RFC3339Nano), time.Since(start), err)

Logs help you debug one request. Metrics show trends.

Track a few signals that usually spike early when timeouts are wrong: count of timeouts by route and dependency, in-flight requests (should level off under load), DB pool wait time, and latency percentiles (p95/p99) split by success vs timeout.

Make slowness predictable. Add a debug-only delay to one handler, slow a DB query with a deliberate wait, or wrap an external call with a test server that sleeps. Then verify two things: you see the timeout error, and the work stops soon after cancellation.

A small load test helps too. Run 20 to 50 concurrent requests for 30 to 60 seconds with one forced slow dependency. Goroutine count and in-flight requests should rise and then level off. If they keep climbing, something is ignoring context cancellation.

Timeouts only help if they're applied everywhere a request can wait. Before you deploy, do one pass over your codebase and confirm the same rules are followed in every handler.

context.DeadlineExceeded and context.Canceled.http.NewRequestWithContext (or req = req.WithContext(ctx)) and the client has transport timeouts (dial, TLS, response header). Avoid relying on http.DefaultClient in production paths.A quick "slow dependency" drill before release is worth it. Add an artificial 2 second delay to one SQL query and confirm three things: the handler returns on time, the DB call actually stops (not just the handler), and your logs clearly say it was a DB timeout.

Imagine an endpoint like GET /v1/account/summary. One user action triggers three things: a PostgreSQL query (account plus recent activity) and two external HTTP calls (for example, a billing status check and a profile enrichment lookup).

Give the whole request a hard 2 second budget. Without a budget, one slow dependency can keep goroutines, DB connections, and memory tied up until your API starts timing out everywhere.

A simple split might be 800ms for the DB query, 600ms for external call A, and 600ms for external call B.

Once you know the overall deadline, pass it down. Each dependency gets its own smaller timeout, but it still inherits cancellation from the parent.

func AccountSummary(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(r.Context(), 2*time.Second)

defer cancel()

dbCtx, dbCancel := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 800*time.Millisecond)

defer dbCancel()

aCtx, aCancel := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 600*time.Millisecond)

defer aCancel()

bCtx, bCancel := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 600*time.Millisecond)

defer bCancel()

// Use dbCtx for QueryContext, aCtx/bCtx for outbound HTTP requests.

}

If external call B slows down and takes 2.5 seconds, your handler should stop waiting at 600ms, cancel the in-flight work, and return a clear timeout response to the client. The client sees a fast failure instead of a hanging spinner.

Your logs should make it obvious what used the budget, for example: DB finished quickly, external A succeeded, external B hit its cap and returned context deadline exceeded.

Once one real endpoint works well with timeouts and cancellation, turn it into a repeatable pattern. Apply it end to end: handler deadline, DB calls, and outbound HTTP. Then copy the same structure to the next endpoint.

You'll move faster if you centralize the boring parts: a boundary timeout helper, wrappers that ensure ctx is passed into DB and HTTP calls, and one consistent error mapping and log format.

If you want to prototype this pattern quickly, Koder.ai (koder.ai) can generate Go handlers and service calls from a chat prompt, and you can export the source code to apply your own timeout helpers and budgets. The goal is consistency: slow calls stop early, errors look the same, and debugging doesn't depend on who wrote the endpoint.

A slow request holds onto limited resources while it waits: a goroutine, memory for buffers and response objects, and often a database connection or HTTP client connection. When enough requests wait at the same time, queues form, latency rises for all traffic, and the service can fail even if each request would eventually finish.

Set a clear deadline at the request boundary (proxy/gateway and in the Go server), derive a timed context in the handler, and pass that ctx into every blocking call (database and outbound HTTP). When the deadline is hit, return quickly with a consistent timeout response and stop any in-flight work that supports cancellation.

Use context.WithTimeout(parent, d) when you want “stop after this duration,” which is the most common in handlers. Use context.WithDeadline(parent, t) when you already have a fixed cutoff time to honor. Use context.WithCancel(parent) when some internal condition should stop work early, like “we already have an answer” or “the client disconnected.”

Always call the cancel function, typically with defer cancel() right after creating the derived context. Canceling releases the timer and lets any child work get a clear stop signal, especially in code paths that return early before the deadline triggers.

Create the request context once in the handler and pass it down as the first argument to functions that may block. A quick check is to search for context.Background() or context.TODO() in request code paths; those often break cancellation propagation by disconnecting work from the request’s deadline.

Use context-aware database methods like QueryContext, QueryRowContext, and ExecContext (or the equivalents in your driver). When the context ends, the driver can ask PostgreSQL to cancel the query so you don’t keep burning time and connections after the request is already over.

Attach the parent request context to the outbound request using http.NewRequestWithContext(ctx, ...), and also configure client/transport timeouts so you’re protected during connect, TLS, and waiting for response headers. Even on errors or non-200 responses, always close the response body so connections return to the pool.

Pick one total budget for the request first, then give each dependency a smaller slice that fits within it, leaving a small buffer for handler overhead and response encoding. If the parent context has little time left, avoid starting expensive work that can’t realistically finish before the deadline.

A common default is mapping context.DeadlineExceeded to 504 Gateway Timeout with a short message like “request timed out.” For context.Canceled, it usually means the client disconnected; often the best action is to stop work and return without writing a body, so you don’t waste more resources.

The most frequent ones are dropping the request context by using context.Background(), starting retries or sleeps without checking ctx.Done(), and forgetting to attach ctx to blocking calls. Another subtle issue is stacking many unrelated timeouts everywhere, which makes failures hard to reason about and can cause surprising early cutoffs.