Sep 29, 2025·7 min

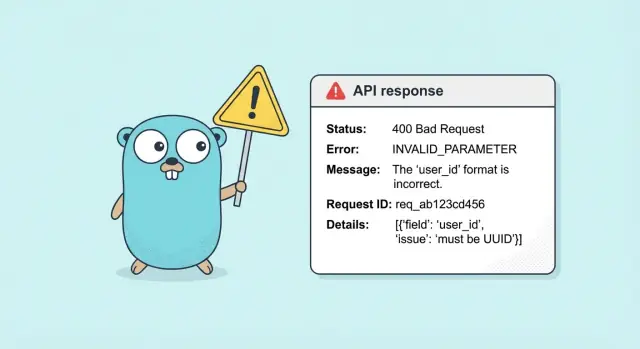

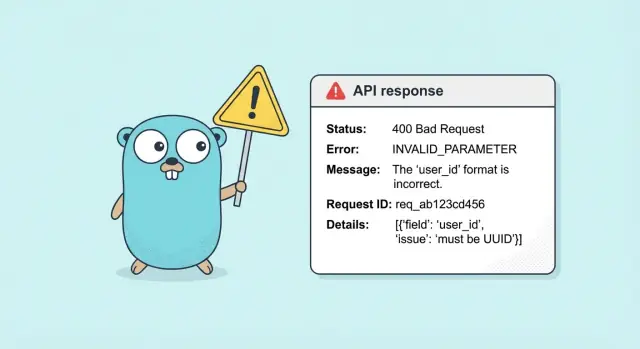

Go API error handling patterns for clear, consistent responses

Go API error handling patterns that standardize typed errors, HTTP status codes, request IDs, and safe messages without leaking internals.

Go API error handling patterns that standardize typed errors, HTTP status codes, request IDs, and safe messages without leaking internals.

When each endpoint reports failures differently, clients stop trusting your API. One route returns { "error": "not found" }, another returns { "message": "missing" }, and a third sends plain text. Even if the meaning is close, client code now has to guess what happened.

The cost shows up fast. Teams build brittle parsing logic and add special cases per endpoint. Retries get risky because the client can’t tell “try again later” from “your input is wrong.” Support tickets increase because the client only sees a vague message, and your team can’t easily match it to a server-side log line.

A common scenario: a mobile app calls three endpoints during signup. The first returns HTTP 400 with a field-level error map, the second returns HTTP 500 with a stack trace string, and the third returns HTTP 200 with { "ok": false }. The app team ships three different error handlers, and your backend team still gets reports like “signup sometimes fails” with no clear clue where to start.

The goal is one predictable contract. Clients should be able to reliably read what happened, whether it’s their fault or yours, whether retry makes sense, and a request ID they can paste into support.

Scope note: this focuses on JSON HTTP APIs (not gRPC), but the same ideas apply anywhere you return errors to other systems.

Pick one clear contract for errors and make every endpoint obey it. “Consistent” means the same JSON shape, the same meaning of fields, and the same behavior no matter which handler fails. Once you do that, clients stop guessing and start handling errors.

A useful contract helps clients decide what to do next. For most apps, every error response should answer three questions:

A practical set of rules:

Decide up front what must never show up in responses. Common “never” items include SQL fragments, stack traces, internal hostnames, secrets, and raw error strings from dependencies.

Keep a clean split: a short user-facing message (safe, polite, actionable) and internal details (full error, stack, and context) kept in logs. For example, “Could not save your changes. Please try again.” is safe. “pq: duplicate key value violates unique constraint users_email_key” is not.

When every endpoint follows the same contract, clients can build one error handler and reuse it everywhere.

Clients can only handle errors cleanly if every endpoint answers in the same shape. Pick one JSON envelope and keep it stable.

A practical default is an error object plus a top-level request_id:

{

"error": {

"code": "VALIDATION_FAILED",

"message": "Some fields are invalid.",

"details": {

"fields": {

"email": "must be a valid email address"

}

}

},

"request_id": "req_01HV..."

}

The HTTP status gives the broad category (400, 401, 409, 500). The machine-readable error.code gives the specific case the client can branch on. That separation matters because many different problems share the same status. A mobile app may show different UI for EMAIL_TAKEN vs WEAK_PASSWORD, even if both are 400.

Keep error.message safe and human. It should help the user fix the problem, but never leak internals (SQL, stack traces, provider names, file paths).

Optional fields are useful when they stay predictable:

details.fields as a map of field to message.details.retry_after_seconds.details.docs_hint as plain text (not a URL).For backward compatibility, treat error.code values as part of your API contract. Add new codes without changing old meanings. Only add optional fields, and assume clients will ignore fields they don’t recognize.

Error handling gets messy when every handler invents its own way to signal failure. A small set of typed errors fixes that: handlers return known error types, and one response layer turns them into consistent responses.

A practical starter set covers most endpoints:

The key is stability at the top level, even if the root cause changes. You can wrap lower-level errors (SQL, network, JSON parsing) while still returning the same public type that middleware can detect.

type NotFoundError struct {

Resource string

ID string

Err error // private cause

}

func (e NotFoundError) Error() string { return "not found" }

func (e NotFoundError) Unwrap() error { return e.Err }

In your handler, return NotFoundError{Resource: "user", ID: id, Err: err} instead of leaking sql.ErrNoRows directly.

To check errors, prefer errors.As for custom types and errors.Is for sentinel errors. Sentinel errors (like var ErrUnauthorized = errors.New("unauthorized")) work for simple cases, but custom types win when you need safe context (like which resource was missing) without changing your public response contract.

Be strict about what you attach:

Err, stack info, raw SQL errors, tokens, user data.That split lets you help clients without exposing internals.

Once you have typed errors, the next job is boring but essential: the same error type should always produce the same HTTP status. Clients will build logic around it.

A practical mapping that works for most APIs:

| Error type (example) | Status | When to use it |

|---|---|---|

| BadRequest (malformed JSON, missing required query param) | 400 | The request is not valid at a basic protocol or format level. |

| Unauthenticated (no/invalid token) | 401 | The client needs to authenticate. |

| Forbidden (no permission) | 403 | Auth is valid, but access is not allowed. |

| NotFound (resource ID does not exist) | 404 | The requested resource is not there (or you choose to hide existence). |

| Conflict (unique constraint, version mismatch) | 409 | The request is well-formed, but it clashes with current state. |

| ValidationFailed (field rules) | 422 | The shape is fine, but business validation fails (email format, min length). |

| RateLimited | 429 | Too many requests in a time window. |

| Internal (unknown error) | 500 | Bug or unexpected failure. |

| Unavailable (dependency down, timeout, maintenance) | 503 | Temporary server-side issue. |

Two distinctions that prevent a lot of confusion:

Retry guidance matters:

A request ID is a short unique value that identifies one API call end to end. If clients can see it in every response, support becomes simple: “Send me the request ID” is often enough to find the exact logs and the exact failure.

This habit pays off for both success and error responses.

Use one clear rule: if the client sends a request ID, keep it. If not, create one.

X-Request-Id).Put the request ID in three places:

request_id in your standard schema)For batch endpoints or background jobs, keep a parent request ID. Example: a client uploads 200 rows, 12 fail validation, and you enqueue work. Return one request_id for the whole call, and include a parent_request_id on each job and each per-item error. That way, you can trace “one upload” even when it fans out into many tasks.

Clients need a clear, stable error response. Your logs need the messy truth. Keep those two worlds separate: return a safe message and a public error code to the client, while logging the internal cause, stack, and context on the server.

Log one structured event for every error response, searchable by request_id.

Fields that are worth keeping consistent:

Store internal details only in server logs (or an internal error store). The client should never see raw database errors, query text, stack traces, or provider messages. If you run multiple services, an internal field like source (api, db, auth, upstream) can speed up triage.

Watch noisy endpoints and rate-limited errors. If an endpoint can produce the same 429 or 400 thousands of times per minute, avoid log spam: sample repeated events, or lower severity for expected errors while still counting them in metrics.

Metrics catch problems earlier than logs. Track counts grouped by HTTP status and error code, and alert on sudden spikes. If RATE_LIMITED jumps 10x after a deploy, you’ll see it quickly even if logs are sampled.

The easiest way to make errors consistent is to stop handling them “everywhere” and route them through one small pipeline. That pipeline decides what the client sees and what you keep for logs.

Start with a small set of error codes clients can depend on (for example: INVALID_ARGUMENT, NOT_FOUND, UNAUTHORIZED, CONFLICT, INTERNAL). Wrap them in a typed error that exposes only safe, public fields (code, safe message, optional details like which field is wrong). Keep internal causes private.

Then implement one translator function that turns any error into (statusCode, responseBody). This is where typed errors map to HTTP status codes, and unknown errors become a safe 500 response.

Next, add middleware that:

request_idA panic should never dump stack traces to the client. Return a normal 500 response with a generic message, and log the full panic with the same request_id.

Finally, change your handlers so they return an error instead of writing the response directly. One wrapper can call the handler, run the translator, and write JSON in the standard format.

A compact checklist:

Golden tests matter because they lock the contract. If someone later changes a message or status code, tests fail before clients get surprised.

Imagine one endpoint: a client app creates a customer record.

POST /v1/customers with JSON like { "email": "[email protected]", "name": "Pat" }. The server always returns the same error shape and always includes a request_id.

The email is missing or badly formatted. The client can highlight the field.

{

"request_id": "req_01HV9N2K6Q7A3W1J9K8B",

"error": {

"code": "VALIDATION_FAILED",

"message": "Some fields need attention.",

"details": {

"fields": {

"email": "must be a valid email address"

}

}

}

}

The email already exists. The client can suggest signing in or choosing another email.

{

"request_id": "req_01HV9N3C2D0F0M3Q7Z9R",

"error": {

"code": "ALREADY_EXISTS",

"message": "A customer with this email already exists."

}

}

A dependency is down. The client can retry with backoff and show a calm message.

{

"request_id": "req_01HV9N3X8P2J7T4N6C1D",

"error": {

"code": "TEMPORARILY_UNAVAILABLE",

"message": "We could not save your request right now. Please try again."

}

}

With one contract, the client reacts consistently:

details.fieldsrequest_id as a support IDFor support, that same request_id is the fastest path to the real cause in internal logs, without exposing stack traces or database errors.

The fastest way to annoy API clients is to make them guess. If one endpoint returns { "error": "..." } and another returns { "message": "..." }, every client turns into a pile of special cases, and bugs hide for weeks.

A few mistakes show up again and again:

code clients can key off.request_id only on failures, so you can’t correlate a user report with the successful call that triggered a later issue.Leaking internals is the easiest trap to fall into. A handler returns err.Error() because it’s convenient, then a constraint name or a third-party message ends up in production responses. Keep the client message safe and short, and put the detailed cause in logs.

Relying on text alone is another slow burn. If the client has to parse English sentences like “email already exists,” you can’t change wording without breaking logic. Stable error codes let you adjust messages, translate them, and keep behavior consistent.

Treat error codes as part of your public contract. If you must change one, add a new code and keep the old code working for a while, even if both map to the same HTTP status.

Finally, include the same request_id field in every response, success or failure. When a user says “it worked, then it broke,” that one ID often saves an hour of guessing.

Before release, do a quick pass for consistency:

error.code, error.message, request_id).VALIDATION_FAILED, NOT_FOUND, CONFLICT, UNAUTHORIZED). Add tests so handlers can’t return unknown codes by accident.request_id and log it for every request, including panics and timeouts.After that, spot-check a few endpoints manually. Trigger a validation error, a missing record, and an unexpected failure. If responses look different across endpoints (fields change, status codes drift, messages overshare), fix the shared pipeline before you add more features.

A practical rule: if a message would help an attacker or confuse a normal user, it belongs in logs, not in the response.

Write down the error contract you want every endpoint to follow, even if your API is already live. A shared contract (status, stable error code, safe message, and request_id) is the fastest way to make errors predictable for clients.

Then migrate gradually. Keep your existing handlers, but route their failures through one mapper that turns internal errors into your public response shape. This improves consistency without a risky big rewrite, and it prevents new endpoints from inventing new formats.

Keep a small error code catalog and treat it like part of your API. When someone wants to add a new code, do a quick review: is it truly new, is it named clearly, and does it map to the right HTTP status?

Add a handful of tests that catch drift:

request_id.error.code is present and comes from the catalog.error.message stays safe and never includes internal details.If you’re building a Go backend from scratch, it can help to lock the contract in early. For example, Koder.ai (koder.ai) includes a planning mode where you can define conventions like an error schema and code catalog upfront, then keep handlers aligned as the API grows.

Use one JSON shape for every error response, across every endpoint. A practical default is a top-level request_id plus an error object with code, message, and optional details so clients can reliably parse and react.

Return error.message as a short, user-safe sentence and keep the real cause in server logs. Don’t return raw database errors, stack traces, internal hostnames, or dependency messages, even if it feels helpful during development.

Use a stable error.code for machine logic and let the HTTP status describe the broad category. Clients should branch on error.code (like ALREADY_EXISTS) and treat the status as guidance (like 409 meaning a state conflict).

Use 400 when the request can’t be reliably parsed or interpreted (malformed JSON, wrong types). Use 422 when the request is well-formed but fails business rules (invalid email format, password too short).

Use 409 when the input is valid but can’t be applied because it conflicts with current state (email already taken, version mismatch). Use 422 for field-level validation where changing the value fixes it without needing a different server state.

Create a small set of typed errors (validation, not found, conflict, unauthorized, internal) and have handlers return them. Then use one shared translator to map those types to status codes and the standard JSON response shape.

Always return a request_id in every response, success or failure, and log it on every server log line. If a client reports an issue, that one ID should be enough to find the exact failure path in logs.

Return 200 only when the operation succeeded, and use 4xx/5xx for errors. Hiding errors behind 200 forces clients to parse body fields and creates inconsistent behavior across endpoints.

Default to no retry for 400, 401, 403, 404, 409, and 422 because retries won’t help without changes. Allow retry for 503, and sometimes 429 after waiting; if you support idempotency keys, retries become safer for POST on transient failures.

Lock the contract with a few “golden” tests that assert status, error.code, and presence of request_id. Add new error codes without changing old meanings, and only add optional fields so older clients keep working.