Jan 16, 2026·8 min

Document-centric workflows: data model and UI patterns

Document-centric workflows explained with practical data models and UI patterns for versions, previews, metadata, and clear status states.

Document-centric workflows explained with practical data models and UI patterns for versions, previews, metadata, and clear status states.

An app is document-centric when the document itself is the product users create, review, and rely on. The experience is built around files like PDFs, images, scans, and receipts, not around a form where a file is just an attachment.

In document-centric workflows, people do real work inside the document: they open it, check what changed, add context, and decide what happens next. If the document can’t be trusted, the app stops being useful.

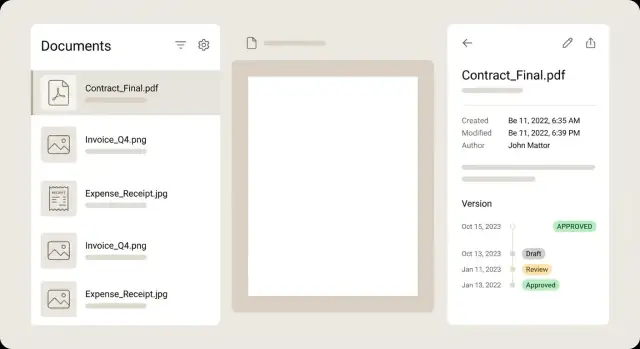

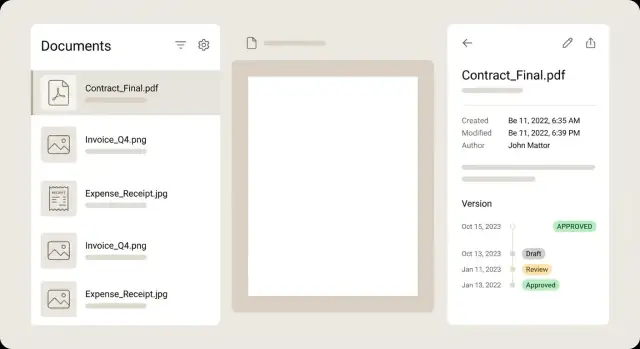

Most document-centric apps need a few core screens early:

The problems show up quickly. Users upload the same receipt twice. Someone edits a PDF and re-uploads it without explaining why. A scan has no date, no vendor, and no owner. Weeks later, nobody knows which version was approved or what the decision was based on.

A good document-centric app feels fast and dependable. Users should be able to answer these questions in seconds:

That clarity comes from definitions. Before you build screens, decide what “version,” “preview,” “metadata,” and “status” mean in your app. If those terms are fuzzy, you’ll get duplicates, confusing history, and review flows that don’t match real work.

The UI often looks simple (a list, a viewer, a few buttons), but the data model carries the weight. If the core objects are right, audit history, fast previews, and reliable approvals become much easier.

Start by separating the “document record” from the “file content.” The record is what users talk about (Invoice from ACME, Taxi receipt). The content is the bytes (PDF, JPG) that may be replaced, reprocessed, or moved without changing what the document means inside the app.

A practical set of objects to model:

Decide what gets an ID that never changes. A useful rule is: Document ID lives forever, while Files and Previews can be regenerated. Versions also need stable IDs, because people reference “what it looked like yesterday” and you’ll need an audit trail.

Model relationships explicitly. A Document has many Versions. Each Version can have multiple Previews (different sizes or formats). This keeps list screens fast because they can load lightweight preview data, while detail screens load the full file only when needed.

Example: a user uploads a crumpled receipt photo. You create a Document, store the original File, generate a thumbnail Preview, and create Version 1. Later, the user uploads a clearer scan. That becomes Version 2, without breaking comments, approvals, or search tied to the Document.

People expect a document to change over time without “turning into” a different item. The simplest way to deliver that is to separate identity (the Document) from content (the Version and Files).

Start with a stable document_id that never changes. Even if the user re-uploads the same PDF, replaces a blurry photo, or uploads a corrected scan, it should still be the same document record. Comments, assignments, and audit logs attach cleanly to one durable ID.

Treat every meaningful change as a new version row. Each version should capture who created it and when, plus storage pointers (file key, checksum, size, page count) and derived artifacts (OCR text, preview images) tied to that exact file. Avoid “editing in place.” It looks simpler at first, but it breaks traceability and makes bugs hard to unwind.

For fast reads, keep a current_version_id on the document. Most screens only need “the latest,” so you don’t have to sort versions on every load. When you need history, load versions separately and show a clean timeline.

Rollbacks are just a pointer change. Instead of deleting anything, set current_version_id back to an older version. It’s quick, safe, and keeps the audit trail intact.

To keep history understandable, record why each version exists. A small, consistent reason field (plus an optional note) prevents a timeline full of mystery updates. Common reasons include re-upload replacement, scan cleanup, OCR correction, redaction, and approval edit.

Example: a finance team uploads a receipt photo, replaces it with a clearer scan, then fixes OCR so the total is readable. Each step is a new version, but the document stays one item in the inbox. If the OCR fix was wrong, rollback is one click because you’re only switching current_version_id.

In document-centric workflows, the preview is often the main thing users interact with. If previews are slow or flaky, the whole app feels broken.

Treat preview generation as a separate job, not something the upload screen waits for. Save the original file first, return control to the user, then generate previews in the background. This keeps the UI responsive and makes retries safe.

Store multiple preview sizes. One size never fits every screen: a tiny thumbnail for lists, a medium image for split views, and full-page images for detailed review (page-by-page for PDFs).

Track preview state explicitly so the UI always knows what to show: pending, ready, failed, and needs_retry. Keep the labels user-friendly in the UI, but keep the states clear in the data.

To keep rendering fast, cache derived values alongside the preview record instead of recalculating them on every view. Common fields include page count, preview width and height, rotation (0/90/180/270), and an optional “best page for thumbnail.”

Design for slow and messy files. A 200-page scanned PDF or a wrinkled receipt photo can take time to process. Use progressive loading: show the first ready page as soon as it exists, then fill in the rest.

Example: a user uploads 30 receipt photos. The list view shows thumbnails as “pending,” then each card flips to “ready” as its preview finishes. If a few fail due to a corrupted image, they stay visible with a clear retry action instead of disappearing or blocking the whole batch.

Metadata turns a pile of files into something you can search, sort, review, and approve. It helps people answer simple questions fast: What is this document? Who is it from? Is it valid? What should happen next?

A practical way to keep metadata clean is to separate it by where it comes from:

These buckets prevent arguments later. If a total amount is wrong, you can see whether it came from OCR or a human edit.

For receipts and invoices, a small set of fields pays off if you use them consistently (same naming, same formats). Common anchor fields are vendor, date, total, currency, and document_number. Keep them optional at first. People upload partial scans and blurry photos, and blocking progress because one field is missing slows the whole workflow.

Treat unknown values as first-class. Use explicit states like null/unknown, plus a reason when helpful (missing page, unreadable, not applicable). That lets the document move forward while still showing reviewers what needs attention.

Also store provenance and confidence for extracted fields. Source might be user, OCR, import, or API. Confidence can be a 0-1 score or a small set like high/medium/low. If OCR reads “$18.70” with low confidence because the last digit is smudged, the UI can highlight it and ask for a quick confirmation.

Multi-page documents need one extra decision: what belongs to the whole document versus a single page. Totals and vendor usually belong to the document. Page-level notes, redactions, rotation, and per-page classification often belong at the page level.

Status answers one question: “Where is this document in the process?” Keep it small and boring. If you add a new status every time someone asks, you’ll end up with filters nobody trusts.

A practical set of business states that maps to real decisions:

Keep “processing” out of business status. OCR running and preview generating describe what the system is doing, not what a person should do next. Store those as separate processing states.

Also separate assignment from status (assignee_id, team_id, due_date). A document can be Approved but still assigned for follow-up, or Needs review with no owner yet.

Record status history, not just the current value. A simple log like (from_status, to_status, changed_at, changed_by, reason) pays off when someone asks, “Who rejected this receipt and why?”

Finally, decide which actions are allowed in each status. Keep rules simple: Imported can move to Needs review; Approved is read-only unless a new version is created; Rejected can be reopened but must keep the prior reason.

Most time is spent scanning a list, opening one item, fixing a few fields, and moving on. Good UI makes those steps quick and predictable.

For the document list, treat each row like a summary so users can decide without opening every file. A strong row shows a small thumbnail, a clear title, a few key fields (merchant, date, total), a status badge, and a subtle warning when something needs attention.

Keep the detail view calm and scannable. A common layout is preview on the left and metadata on the right, with edit controls next to each field. Users should be able to zoom, rotate, and flip pages without losing their place in the form. If a field is extracted from OCR, show a small confidence hint, and ideally highlight the source area on the preview when the field is focused.

Versions work best as a timeline, not a dropdown. Show who changed what and when, and let users open any past version in read-only mode. If you offer comparison, focus on metadata differences (amount changed, vendor corrected) rather than forcing a pixel-by-pixel PDF compare.

Review mode should optimize for speed. A keyboard-first triage flow is often enough: quick approve/reject actions, fast fixes for common fields, and a short comment box for rejections.

Empty states matter because documents are often mid-processing. Instead of a blank box, explain what’s happening: “Preview is generating,” “OCR is running,” or “This file type has no preview yet.”

A simple workflow feels like “upload, check, approve.” Under the hood, it works best when you separate the file itself (versions and previews) from the business meaning (metadata and status).

The user uploads a PDF, photo, or receipt scan and immediately sees it in an inbox list. Don’t wait for processing to finish. Show a filename, upload time, and a clear badge like “Processing.” If you already know the source (email import, mobile camera, drag-and-drop), show it too.

On upload, create a Document record (the long-lived thing) and a Version record (this specific file). Set current_version_id to the new version. Store preview_state = pending and extraction_state = pending so the UI can be honest about what’s ready.

The detail view should open immediately, but show a placeholder viewer and a clear “Preparing preview” message instead of a broken frame.

A background job creates thumbnails and a viewable preview (page images for PDFs, resized images for photos). Another job extracts metadata (vendor, date, total, currency, document type). When each job finishes, update only its state and timestamps so you can retry failures without touching everything else.

Keep the UI compact: show preview state, data state, and highlight fields with low confidence.

When the preview is ready, reviewers fix fields, add notes, and move the document through business states like Imported -> Needs review -> Approved (or Rejected). Log who changed what and when.

If a reviewer uploads a corrected file, it becomes a new Version and the document returns to Needs review automatically.

Exports, accounting sync, or internal reports should read from current_version_id and the approved metadata snapshot, not “latest extraction.” That prevents a half-processed re-upload from changing numbers.

Document-centric workflows fail for boring reasons: early shortcuts turn into daily pain once people upload duplicates, correct mistakes, or ask, “Who changed this and when?”

Treating the file name as the document’s identity is a classic mistake. Names change, users re-upload, and cameras produce duplicates like IMG_0001. Give each document a stable ID, and treat the file name as a label.

Overwriting the original file when someone uploads a replacement also causes trouble. It feels simpler, but you lose your audit trail and can’t answer basic questions later (what was approved, what was edited, what was sent). Keep the binary file immutable and add a new version record.

Status confusion creates subtle bugs. “OCR running” is not the same as “Needs review.” Processing states describe what the system is doing; business status describes what a person should do next. When those are mixed, documents end up stuck in the wrong bucket.

UI decisions can create friction too. If you block the screen until previews are generated, people experience the app as slow even when the upload succeeded. Show the document right away with a clear placeholder, then swap in thumbnails when ready.

Finally, metadata becomes untrustworthy when you store values without provenance. If the total came from OCR, say so. Keep timestamps.

A quick gut-check list:

Example: in a receipts app, a user re-uploads a clearer photo. If you version it, keep the old image, mark OCR as reprocessing, and keep Needs review until a human confirms the amount.

Document-centric workflows feel “done” only when people can trust what they see and recover when things go wrong. Before launch, test with messy, real documents (blurry receipts, rotated PDFs, repeated uploads).

Five checks that catch most surprises:

A quick reality test: ask someone to review three similar receipts and intentionally make one wrong change. If they can spot the current version, understand the status, and fix the mistake in under a minute, you’re close.

Monthly receipt reimbursements are a clear example of document-centric work. An employee uploads receipts, then two reviewers check them: a manager, then finance. The receipt is the product, so your app lives or dies on versioning, previews, metadata, and clear status.

Jamie uploads a photo of a taxi receipt. Your system creates Document #1842 with Version v1 (the original file), a thumbnail and preview, and metadata like merchant, date, currency, total, and an OCR confidence score. The document starts in Imported, then moves to Needs review once preview and extraction are ready.

Later, Jamie accidentally uploads the same receipt again. A duplicate check (file hash plus similar merchant/date/total) can surface a simple choice: “Looks like a duplicate of #1842. Attach anyway or discard.” If they attach, store it as another File linked to the same Document so you keep one review thread and one status.

During review, the manager sees the preview, key fields, and warnings. OCR guessed the total as $18.00, but the image clearly shows $13.00. Jamie corrects the total. Don’t overwrite history. Create Version v2 with updated fields, keep v1 unchanged, and log “Total corrected by Jamie.”

If you want to build this kind of workflow quickly, Koder.ai (koder.ai) can help you generate the first version of the app from a chat-based plan, but the same rule applies: define the objects and states first, then let the screens follow.

Practical next steps:

A document-centric app treats the document as the main thing users work on, not as a side attachment. People need to open it, trust what they see, understand what changed, and decide what happens next based on that document.

Start with an inbox/list, a document detail view with a fast preview, a simple review action area (approve/reject/request changes), and a way to export or share. These four screens cover the common loop of find, open, decide, and hand off.

Model a stable Document record that never changes, and store actual file bytes as separate File objects. Then add Version as the snapshot that ties a document to a specific file (and its derived outputs). This separation keeps comments, assignments, and history intact even when the file is replaced.

Make each meaningful change a new version instead of editing in place. Keep a current_version_id on the document for fast “latest” reads, and store a timeline of older versions for audit and rollback. This prevents confusion about what was approved and why.

Generate previews asynchronously after saving the original file, so uploads feel instant and retries are safe. Track preview state like pending/ready/failed so the UI can be honest, and store multiple sizes so list views stay lightweight while detail views stay sharp.

Store metadata in three buckets: system (file size, type), extracted (OCR fields and confidence), and user-entered corrections. Keep provenance so you can tell whether a value came from OCR or a person, and avoid forcing every field to be filled before work can continue.

Use a small set of business statuses that describe what a person should do next, such as Imported, Needs review, Approved, Rejected, and Archived. Track processing separately (preview/OCR running) so documents don’t end up “stuck” in a status that mixes human work with machine work.

Store immutable file checksums and compare them on upload, then add a second check using key fields like vendor/date/total when available. When you suspect a duplicate, offer a clear choice to attach it to the same document thread or discard it, so you don’t split review history across copies.

Keep a status history log with who changed what, when, and why, and keep versions readable via a timeline. Rollback should be a pointer change back to an older version, not a delete, so you can recover quickly without losing the audit trail.

Define the objects and states first, then let the UI follow those definitions. If you use Koder.ai to generate an app from a chat plan, be explicit about Document/Version/File, preview and extraction states, and status rules, so the generated screens map cleanly to real workflow behavior.