Nov 19, 2025·7 min

Custom domain troubleshooting checklist for DNS and SSL issues

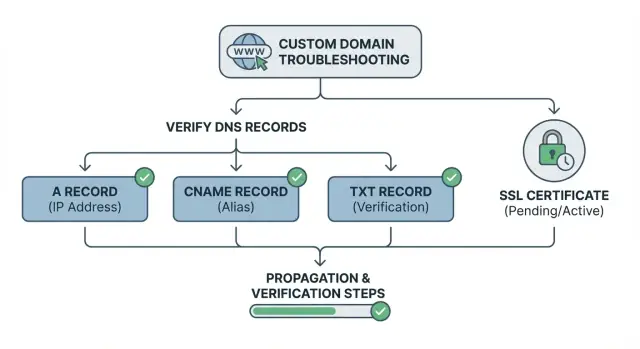

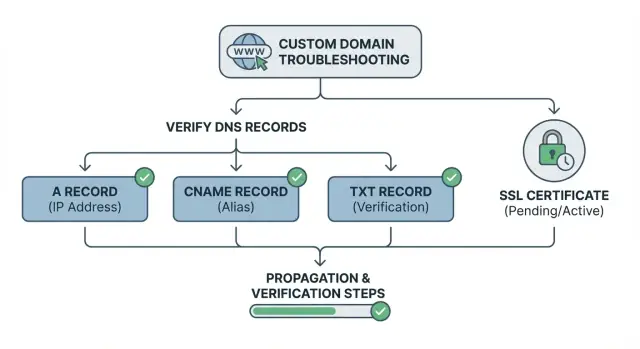

Use this custom domain troubleshooting checklist to diagnose DNS record issues, propagation delays, and SSL timing, with simple verification steps.

Use this custom domain troubleshooting checklist to diagnose DNS record issues, propagation delays, and SSL timing, with simple verification steps.

“Custom domain not working” is a catch-all phrase for a few different failures. Your browser shows the symptom, not the cause. Before changing anything, name what you’re actually seeing.

Typical symptoms include:

Most of the time, only one thing is wrong:

Before troubleshooting, make sure you have access to two places: where you edit DNS records (registrar or DNS provider) and where you attach the domain on the hosting side. For example, if you’re connecting a deployed app on Koder.ai to a custom domain, you need DNS access for the domain and the domain settings in the app’s hosting or deployment setup.

Some fixes are instant (like correcting a typo). Others take time. DNS changes can take a while to show up, and SSL usually won’t complete until DNS points correctly and the domain is reachable. The goal is to stop guessing and confirm each layer in order.

Most domain issues come down to a mismatch between (1) the hostname you’re testing, (2) where DNS is managed, and (3) what the record actually points to. Once those three line up, SSL is usually the last step.

Domains have two common forms: the root domain (example.com, also called the apex) and subdomains (www.example.com, app.example.com). They’re related, but they can have different DNS records. So it’s normal for www to work while the apex fails, or the other way around.

Nameservers decide who is in charge of your DNS zone. If you bought a domain from one company but the nameservers point to another, you must edit DNS where the nameservers point. Many “I updated it but nothing changed” situations happen because the records were edited in the wrong dashboard.

Here’s what the main record types do:

TTL is the “how long to cache this” timer. Lower TTL means caches refresh faster. Higher TTL means you might need to wait longer, even after you fixed the record. Seeing the old value for a while can be normal.

When a custom domain fails, you can usually sort it into one of four buckets: DNS doesn’t resolve, DNS resolves to the wrong place, SSL isn’t ready, or it only fails for some people because of caching.

Use this decision tree:

www works but the root domain doesn’t (or vice versa), you likely configured only one hostname, or you have conflicting redirect rules.Move faster by writing down the exact hostname that fails (apex vs www) and the exact error message. On hosting platforms that automate domains and certificates, the difference between “cannot find host” and “certificate pending” tells you whether to fix DNS records or simply wait for SSL after DNS becomes visible.

Many domain failures start with a simple mismatch: you set up DNS for one hostname, but you’re testing another.

First, write down the exact hostname you want live. The root domain looks like example.com. A subdomain looks like www.example.com or app.example.com. These are separate DNS entries, so “www works” doesn’t mean the root domain will.

Next, find the expected target from your hosting platform. Some platforms give an IP address (for an A or AAAA record). Others give a target hostname (for a CNAME). If your host provides a value in a domain setup screen, treat that as the source of truth.

Before changing anything, capture what’s currently set. Keep it simple:

Also confirm you’re editing the right DNS zone. It’s easy to update the wrong domain, the wrong environment, or the wrong provider account.

Many problems are just the wrong record type for the hostname you’re trying to connect. Start by separating two cases: the root domain (example.com) and a subdomain (www.example.com). They behave differently at many DNS providers.

An A record points a name to an IPv4 address. Many setups use an A record for the root domain because some providers don’t allow a CNAME at the apex. If your host gives you an IP, an A record is usually correct.

An AAAA record is the IPv6 version. A stray AAAA record pointing to an old destination can create confusing “works for me” behavior, because some visitors will hit IPv6 while others hit IPv4. If your host didn’t give you an IPv6 target, removing an incorrect AAAA record often fixes inconsistent failures.

A CNAME record points a subdomain to another hostname (often used for www). It’s useful when the host wants you to target a named endpoint that can change behind the scenes.

A TXT record is for verification and challenges (including some SSL checks). Common mistakes include placing the TXT on the wrong name (root vs _acme-challenge vs a subdomain), adding extra spaces, or pasting the wrong value.

Before moving on, look for conflicts. These are the ones that cause the most trouble:

Many “custom domain not working” cases aren’t about the record value at all. They happen because the record was added at the wrong provider. If your domain uses Provider A’s nameservers, changing records in Provider B’s dashboard won’t do anything, even if the records look correct there.

Check which nameservers your domain is actually using. You can usually see this in your registrar’s domain settings under “Nameservers”. For a second opinion, ask DNS directly from your computer:

dig NS example.com

The nameservers returned by that command are the authoritative ones.

A quick sanity check:

ns1... and ns2..., those exact values must appear at the registrar.If you update records at the wrong provider, you’ll often see two dashboards that don’t match. Only the authoritative nameservers matter.

Also watch for delays after changing nameservers at the registrar. During the transition window, results can look inconsistent depending on where you test from. If nameservers are still changing, pause record edits until the nameserver set is stable, then continue.

“Propagation” isn’t one switch. It’s a chain of DNS caches (ISP, phone carrier, public resolvers, and your own devices) updating at different speeds. That’s why your domain can work for a coworker but fail for you.

TTL (time to live) tells caches how long they can keep an answer. If the old TTL was 1 hour, some people will keep seeing the old value for close to an hour. Lowering TTL helps only if you did it before making the change.

To separate caching delays from real mistakes, do a few quick checks:

If the record is wrong anywhere you check (wrong IP, missing www, old CNAME), fix it. If records look correct in most places but one network still shows the old value, it’s usually cache delay.

SSL certificates usually fail for one basic reason: the certificate provider can’t validate the domain until DNS points to the correct place consistently.

The normal sequence is simple:

Common blockers are easy to miss. A wrong A or CNAME target sends validation checks to the wrong server. A stale AAAA record can override your working A record for some visitors, so HTTPS fails only for them. Missing a required TXT record can prevent a platform from issuing a certificate.

Use symptoms to separate “still issuing” from “misconfigured”:

While you wait, don’t keep flipping records. Every change resets the clock and can create a split world where different networks see different answers. Set the correct records once, then re-check resolution and verification until the certificate is issued.

If you’re using a platform like Koder.ai, the safest flow is the same: confirm DNS points to the expected target, remove incorrect AAAA records if they exist, and give SSL time after DNS is stable.

Good troubleshooting is mostly comparison: what you see versus what you expect. Don’t rely on “it loads on my phone.” Use repeatable checks.

Use a DNS lookup tool (like nslookup or dig) and confirm the returned value matches what you intended (an IP for A or AAAA, a hostname for CNAME, a token for TXT).

# Apex (root) domain

dig example.com A

dig example.com AAAA

# www subdomain

dig www.example.com CNAME

# TXT (often used for verification)

dig example.com TXT

Check both names you might be using: the apex (example.com) and www (www.example.com). It’s common for one to be correct while the other still points somewhere old.

Open both http:// and https:// for the apex and www. You want one clear “home” domain and one clean redirect.

www) and redirect the other to it.If results differ by network, you’re likely seeing caching or propagation. Keep a tiny log: what you changed, where you changed it, the time, and what you observed.

Most DNS and SSL problems aren’t mysteries. They’re small mistakes that keep you checking the wrong thing, or changing things too quickly to get a clear read.

The most common time sink is editing DNS in two places. This often happens after switching nameservers: you update records at the registrar, but DNS is actually hosted elsewhere (or the other way around). Everything looks correct in one dashboard, yet nothing changes publicly.

Another classic mistake is trying to put a CNAME on the root domain with a provider that doesn’t support it. You may need an A record, or an ALIAS or ANAME-style record if your DNS provider offers it.

IPv6 can also cause headaches. Leaving an old AAAA record can send some visitors to the wrong server while others hit IPv4 correctly.

Be careful with “just in case” records. Multiple A records can behave like accidental load balancing if one target is wrong, especially when pointing a custom domain at a hosted app.

One final rule: stop resetting the clock.

Small, calm changes beat constant tweaking.

You launch a new app and set up both example.com and www.example.com. A few minutes later, www.example.com loads fine, but the root domain shows a DNS error, loads an old site, or HTTPS stays pending. This pattern is common, and it usually has a small cause.

Start with the boring question: are you editing DNS in the right place? If your domain is registered at one company but DNS is hosted at another, you can change records all day and nothing will happen. Check nameservers first, then open the DNS panel for the provider those nameservers point to.

Next, compare the two hostnames. www is typically a CNAME. The root domain is trickier: many providers don’t allow a CNAME at the apex, so it often needs an A record to an IP, or an ALIAS or ANAME-style record if supported.

A decision path that works in practice:

example.com has no record (or points elsewhere)? Fix the apex record.The correct end state is boring: both example.com and www.example.com lead to the same app, one is canonical (the other redirects), and HTTPS is valid.

When a domain setup fails, most fixes come from a few fast checks. Run these before changing anything else.

After DNS is clearly correct, then check SSL. Many platforms only issue the certificate after they can resolve your domain to the right target consistently. If you check too early, you can mistake a normal delay for a real error.

If you’re adding a custom domain to a deployed app on Koder.ai, treat the domain setup screen as your reference for the expected target, then re-check the status only after DNS has had time to propagate.

The fastest way to avoid repeating DNS and SSL mistakes is to keep a short “domain setup note” for each project. It’s a reusable runbook you can copy the next time you launch.

Keep it in your project docs and fill it in before you touch DNS:

During launch, make one person the DNS owner. DNS breaks most often when two people “fix” different things at the same time (for example, one changes nameservers while another edits records).

On the hosting side, plan for safe reversals. If your platform supports snapshots or rollback, take a snapshot before changing routing so you can return to the last known-good state quickly. If you build on Koder.ai, you can use Planning Mode to write down the domain steps you’ll take, apply them in order, and roll back if a change breaks production.

If you’ve confirmed DNS is correct and you still see failures, stop guessing and escalate with evidence:

When you escalate, include the hostname, expected records, current resolver results, and timestamps. It turns a slow back-and-forth into a quick fix.

It usually means one layer of the chain is wrong: DNS isn’t resolving, DNS resolves to the wrong target, the server/host doesn’t recognize your hostname, or HTTPS/SSL hasn’t finished issuing yet. Start by writing down the exact error you see and the exact hostname you typed (apex vs www).

Because example.com (the apex) and www.example.com are separate hostnames with separate DNS records. It’s common to have a correct CNAME for www while the apex has no A record, the wrong A record, or an unsupported setup at your DNS provider.

Check the domain’s nameservers at your registrar and compare them to the DNS provider you’re editing. Only the provider listed in the active nameservers is authoritative; editing records anywhere else won’t change what the public internet sees.

Use an A record when your host gives you an IPv4 address, an AAAA record only if your host gives you an IPv6 address, and a CNAME when your host gives you another hostname (most common for www). TXT records are for verification and challenges, and they must be created on the exact name your host specifies.

A stale or wrong AAAA record can send some visitors over IPv6 to an old server while others go to the correct IPv4 address, creating “works for me” confusion. If your host didn’t provide an IPv6 target, removing an incorrect AAAA record is often the simplest fix.

Most often, you’ve configured only one hostname on the hosting side (only apex or only www), or you have competing redirect rules that bounce between HTTP and HTTPS or between apex and www. Pick one canonical hostname, configure both hostnames, and ensure only one clean redirect path exists.

Yes, and waiting is the right move only after DNS clearly points to the correct target from multiple places. SSL issuance usually won’t complete until the domain resolves consistently to the expected destination, and flipping DNS back and forth can keep resetting the process.

TTL is how long resolvers cache an answer, so even after you fix a record, some networks may keep serving the old value until the TTL window expires. Test from two different networks (for example, Wi‑Fi and mobile data) and avoid making new DNS changes every few minutes so you can observe propagation cleanly.

Use a repeatable check like dig or nslookup to confirm the A/AAAA/CNAME/TXT answers match your expected target, and then test both http:// and https:// for both apex and www. If one network shows different DNS answers than another, treat it as caching; if all networks show the wrong answers, treat it as a configuration mistake.

On Koder.ai, treat the app’s domain setup screen as the source of truth for the expected DNS target, then make DNS match that exactly at the authoritative provider. After changing DNS, give it time to settle before re-checking SSL, and use snapshots/rollback if you’re adjusting routing on a live project so you can return to a known-good state quickly.