Nov 14, 2025·8 min

Craig McLuckie and Cloud-Native: Platform Thinking Wins

A practical look at Craig McLuckie’s role in cloud-native adoption and how platform thinking helped containers evolve into reliable production infrastructure.

A practical look at Craig McLuckie’s role in cloud-native adoption and how platform thinking helped containers evolve into reliable production infrastructure.

Teams don’t struggle because they can’t start a container. They struggle because they have to run hundreds of them safely, update them without downtime, recover when things break, and still ship features on schedule.

Craig McLuckie’s “cloud-native” story matters because it isn’t a victory lap about flashy demos. It’s a record of how containers became operable in real environments—where incidents happen, compliance exists, and the business needs predictable delivery.

“Cloud-native” isn’t “running in the cloud.” It’s an approach to building and operating software so it can be deployed frequently, scaled when demand changes, and repaired quickly when parts fail.

In practice, that usually means:

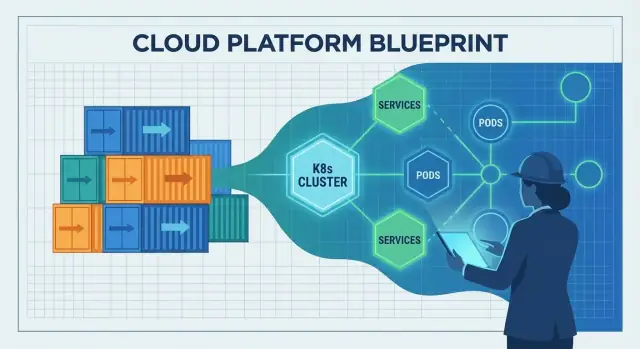

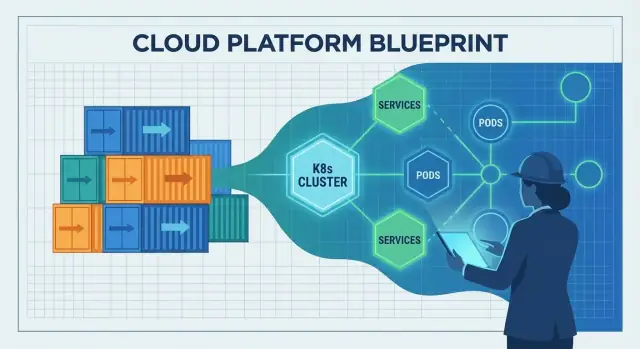

Early container adoption often looked like a toolbox: teams grabbed Docker, stitched scripts together, and hoped operations would keep up. Platform thinking flips that. Instead of each team inventing its own path to production, you build shared “paved roads”—a platform that makes the safe, compliant, observable way also the easy way.

That shift is the bridge from “we can run containers” to “we can run a business on them.”

This is for people responsible for outcomes, not just architecture diagrams:

If your goal is dependable delivery at scale, this history has practical lessons.

Craig McLuckie is one of the best-known names connected to the early cloud-native movement. You’ll see him referenced in conversations about Kubernetes, the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF), and the idea that infrastructure should be treated like a product—not a pile of tickets and tribal knowledge.

It’s worth being precise. McLuckie didn’t single-handedly “invent cloud-native,” and Kubernetes was never a one-person project. Kubernetes was created by a team at Google, and McLuckie was part of that early effort.

What people often credit him for is helping turn an engineering concept into something the broader industry could actually adopt: stronger community building, clearer packaging, and a push toward repeatable operational practices.

Across Kubernetes and the CNCF era, McLuckie’s message has been less about trendy architecture and more about making production predictable. That means:

If you’ve heard phrases like “paved roads,” “golden paths,” or “platform as a product,” you’re circling the same idea: reduce cognitive load for teams by making the right thing the easy thing.

This post isn’t a biography. McLuckie is a useful reference point because his work sits at the intersection of three forces that changed software delivery: containers, orchestration, and ecosystem building. The lessons here aren’t about personality—they’re about why platform thinking ended up being the unlock for running containers in real production.

Containers were an exciting idea long before “cloud-native” became a common label. In everyday terms, a container is a way to package an application together with the files and libraries it needs so it can run the same way on different machines—like shipping a product in a sealed box with all the parts inside.

Early on, many teams used containers for side projects, demos, and developer workflows. They were great for trying new services quickly, spinning up test environments, and avoiding “it works on my laptop” surprises during a handoff.

But moving from a handful of containers to a production system that runs 24/7 is a different job. The tooling was real, yet the operational story was incomplete.

Common issues showed up fast:

Containers helped make software portable, but portability alone didn’t guarantee reliability. Teams still needed consistent deployment practices, clear ownership, and operational guardrails—so containerized apps wouldn’t just run once, but run predictably every day.

Platform thinking is the moment a company stops treating infrastructure as a one-off project and starts treating it like an internal product. The “customers” are your developers, data teams, and anyone who ships software. The product goal isn’t more servers or more YAML—it’s a smoother path from idea to production.

A real platform has a clear promise: “If you build and deploy using these paths, you’ll get reliability, security, and predictable delivery.” That promise requires product habits—documentation, support, versioning, and feedback loops. It also requires a deliberate user experience: sensible defaults, paved roads, and an escape hatch when teams truly need it.

Standardization removes decision fatigue and prevents accidental complexity. When teams share the same deployment patterns, logging, and access controls, problems become repeatable—and therefore solvable. On-call rotations improve because incidents look familiar. Security reviews get faster because the platform bakes in guardrails rather than relying on every team to reinvent them.

This isn’t about forcing everyone into the same box. It’s about agreeing on the 80% that should be boring, so teams can spend their energy on the 20% that differentiates the business.

Before platform approaches took hold, infrastructure often depended on special knowledge: a few people knew which servers were patched, which settings were safe, and which scripts were “the good ones.” Platform thinking replaces that with repeatable patterns: templates, automated provisioning, and consistent environments from dev to production.

Done well, platforms create better governance with less paperwork. Policies become automated checks, approvals become auditable workflows, and compliance evidence is generated as teams deploy—so the organization gets control without slowing everyone down.

Containers made it easy to package and ship an app. The hard part was what happened after you shipped it: picking where it should run, keeping it healthy, and adapting when traffic or infrastructure changed.

That’s the gap Kubernetes filled. It turned “a pile of containers” into something you can operate day after day, even as servers fail, releases happen, and demand spikes.

Kubernetes is often described as “container orchestration,” but the practical problems are more specific:

Without an orchestrator, teams end up scripting these behaviors and managing exceptions by hand—until the scripts don’t match reality.

Kubernetes popularized the idea of a shared control plane: one place where you declare what you want (“run 3 copies of this service”) and the platform continuously works to make the real world match that intent.

This is a big shift in responsibilities:

Kubernetes didn’t appear because containers were trendy. It grew from lessons learned operating large fleets: treat infrastructure like a system with feedback loops, not a set of one-off server tasks. That operational mindset is why it became the bridge from “we can run containers” to “we can run them reliably in production.”

Cloud-native didn’t just introduce new tools—it changed the daily rhythm of shipping software. Teams moved from “hand-crafted servers and manual runbooks” to systems designed to be driven by APIs, automation, and declarative configuration.

A cloud-native setup assumes infrastructure is programmable. Need a database, a load balancer, or a new environment? Instead of waiting for a manual setup, teams describe what they want and let automation create it.

The key shift is declarative config: you define the desired state (“run 3 copies of this service, expose it on this port, limit memory to X”) and the platform continuously works to match that state. This makes changes reviewable, repeatable, and easier to roll back.

Traditional delivery often involved patching live servers. Over time, each machine became a little different—configuration drift that only shows up during an incident.

Cloud-native delivery pushed teams toward immutable deployments: build an artifact once (often a container image), deploy it, and if you need a change, you deploy a new version rather than modifying what’s already running. Combined with automated rollouts and health checks, this approach tends to reduce “mystery outages” caused by one-off fixes.

Containers made it easier to package and run many small services consistently, which encouraged microservice architectures. Microservices, in turn, increased the need for consistent deployment, scaling, and service discovery—areas where container orchestration shines.

The trade-off: more services means more operational overhead (monitoring, networking, versioning, incident response). Cloud-native helps manage that complexity, but it doesn’t erase it.

Portability improved because teams standardized on common deployment primitives and APIs. Still, “run anywhere” usually requires work—differences in security, storage, networking, and managed services matter. Cloud-native is best understood as reducing lock-in and friction, not eliminating them.

Kubernetes didn’t spread only because it was powerful. It spread because it got a neutral home, clear governance, and a place where competing companies could cooperate without one vendor “owning” the rules.

The Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) created shared governance: open decision-making, predictable project processes, and public roadmaps. That matters for teams betting on core infrastructure. When the rules are transparent and not tied to a single company’s business model, adoption feels less risky—and contributions become more attractive.

By hosting Kubernetes and related projects, the CNCF helped turn “a popular open-source tool” into a long-term platform with institutional support. It provided:

With many contributors (cloud providers, startups, enterprises, and independent engineers), Kubernetes evolved faster and in more real-world directions: networking, storage, security, and day-2 operations. Open APIs and standards made it easier for tools to integrate, which reduced lock-in and increased confidence for production use.

CNCF also accelerated an ecosystem explosion: service meshes, ingress controllers, CI/CD tools, policy engines, observability stacks, and more. That abundance is a strength—but it creates overlap.

For most teams, success comes from choosing a small set of well-supported components, favoring interoperability, and being clear about ownership. A “best of everything” approach often leads to maintenance burden rather than better delivery.

Containers and Kubernetes solved a big part of the “how do we run software?” question. They didn’t automatically solve the harder one: “how do we keep it running when real users show up?” The missing layer is operational reliability—clear expectations, shared practices, and a system that makes the right behaviors the default.

A team can ship quickly and still be one bad deploy away from chaos if the production baseline is undefined. At minimum, you need:

Without this baseline, every service invents its own rules, and reliability becomes a matter of luck.

DevOps and SRE introduced important habits: ownership, automation, measured reliability, and learning from incidents. But habits alone don’t scale across dozens of teams and hundreds of services.

Platforms make those practices repeatable. SRE sets goals (like SLOs) and feedback loops; the platform provides paved roads to meet them.

Reliable delivery usually requires a consistent set of capabilities:

A good platform bakes these defaults into templates, pipelines, and runtime policies: standard dashboards, common alert rules, deployment guardrails, and rollback mechanisms. That’s how reliability stops being optional—and starts being a predictable outcome of shipping software.

Cloud-native tooling can be powerful and still feel like “too much” for most product teams. Platform engineering exists to close that gap. The mission is simple: reduce cognitive load for application teams so they can ship features without becoming part-time infrastructure experts.

A good platform team treats internal infrastructure as a product. That means clear users (developers), clear outcomes (safe, repeatable delivery), and a feedback loop. Instead of handing over a pile of Kubernetes primitives, the platform offers opinionated ways to build, deploy, and operate services.

One practical lens is to ask: “Can a developer go from idea to a running service without opening a dozen tickets?” Tools that compress that workflow—while preserving guardrails—are aligned with the cloud-native platform goal.

Most platforms are a set of reusable “paved roads” that teams can choose by default:

The goal isn’t to hide Kubernetes—it’s to package it into sensible defaults that prevent accidental complexity.

In that spirit, Koder.ai can be used as a “DX accelerator” layer for teams that want to spin up internal tools or product features quickly via chat, then export source code when it’s time to integrate with a more formal platform. For platform teams, its planning mode and built-in snapshots/rollback can also mirror the same reliability-first posture you want in production workflows.

Every paved road is a trade: more consistency and safer operations, but fewer one-off options. Platform teams do best when they offer:

You can see platform success in measurable ways: faster onboarding for new engineers, fewer bespoke deployment scripts, fewer “snowflake” clusters, and clearer ownership when incidents happen. If teams can answer “who owns this service and how do we ship it?” without a meeting, the platform is doing its job.

Cloud-native can make delivery faster and operations calmer—but only when teams are clear about what they’re trying to improve. Many slowdowns happen when Kubernetes and its ecosystem are treated as the goal, not the means.

A common mistake is adopting Kubernetes because it’s “what modern teams do,” without a concrete target like shorter lead time, fewer incidents, or better environment consistency. The result is lots of migration work with no visible payoff.

If success criteria aren’t defined up front, every decision becomes subjective: which tool to pick, how much to standardize, and when the platform is “done.”

Kubernetes is a foundation, not a full platform. Teams often bolt on add-ons quickly—service mesh, multiple ingress controllers, custom operators, policy engines—without clear boundaries or ownership.

Over-customization is another trap: bespoke YAML patterns, hand-rolled templates, and one-off exceptions that only the original authors understand. Complexity rises, onboarding slows, and upgrades become risky.

Cloud-native makes it easy to create resources—and easy to forget them. Cluster sprawl, unused namespaces, and over-provisioned workloads quietly inflate costs.

Security pitfalls are just as common:

Start small with one or two well-scoped services. Define standards early (golden paths, approved base images, upgrade rules) and keep the platform surface area intentionally limited.

Measure outcomes like deployment frequency, mean time to recovery, and developer time-to-first-deploy—and treat anything that doesn’t move those numbers as optional.

You don’t “adopt cloud-native” in one move. The teams that succeed follow the same core idea associated with McLuckie’s era: build a platform that makes the right way the easy way.

Start small, then codify what works.

If you’re experimenting with new workflows, a useful pattern is to prototype the “golden path” experience end-to-end before you standardize it. For example, teams may use Koder.ai to quickly generate a working web app (React), backend (Go), and database (PostgreSQL) through chat, then treat the resulting codebase as a starting point for the platform’s templates and CI/CD conventions.

Before you add tooling, ask:

Track outcomes, not tool usage:

If you want examples of what good “platform MVP” packages look like, see /blog. For budgeting and rollout planning, you can also reference /pricing.

The big lesson from the last decade is simple: containers didn’t “win” because they were clever packaging. They won because platform thinking made them dependable—repeatable deployments, safe rollouts, consistent security controls, and predictable operations.

The next chapter isn’t about a single breakout tool. It’s about making cloud-native feel boring in the best way: fewer surprises, fewer one-off fixes, and a smoother path from code to production.

Policy-as-code becomes a default. Instead of reviewing every deployment manually, teams codify rules for security, networking, and compliance so guardrails are automatic and auditable.

Developer experience (DX) gets treated as a product. Expect more focus on paved roads: templates, self-service environments, and clear golden paths that reduce cognitive load without limiting autonomy.

Simpler ops, not more dashboards. The best platforms will hide complexity: opinionated defaults, fewer moving parts, and reliability patterns that are built in rather than bolted on.

Cloud-native progress slows when teams chase features instead of outcomes. If you can’t explain how a new tool reduces lead time, lowers incident rates, or improves security posture, it’s probably not a priority.

Assess your current delivery pain points and map them to platform needs:

Treat the answers as your platform backlog—and measure success by the outcomes your teams feel every week.

Cloud-native is an approach to building and operating software so you can deploy frequently, scale when demand changes, and recover quickly from failures.

In practice it usually includes containers, automation, smaller services, and standard ways to observe, secure, and govern what’s running.

A container helps you ship software consistently, but it doesn’t solve the hard production problems on its own—like safe upgrades, service discovery, security controls, and durable observability.

The gap appears when you move from a handful of containers to hundreds running 24/7.

“Platform thinking” means treating internal infrastructure like an internal product with clear users (developers) and a clear promise (safe, repeatable delivery).

Instead of every team stitching together its own path to production, the org builds shared paved roads (golden paths) with sensible defaults and support.

Kubernetes provides the operational layer that turns “a pile of containers” into a system you can run day after day:

It also introduces a shared where you declare desired state and the system works to match it.

Declarative config means you describe what you want (desired state) rather than writing step-by-step procedures.

Practical benefits include:

Immutable deployments mean you don’t patch live servers in place. You build an artifact once (often a container image) and deploy that exact artifact.

To change something, you ship a new version rather than modifying the running system. This helps reduce configuration drift and makes incidents easier to reproduce and roll back.

CNCF provided a neutral governance home for Kubernetes and related projects, which reduced the risk of betting on core infrastructure.

It helped with:

A production baseline is the minimum set of capabilities and practices that make reliability predictable, such as:

Without it, each service invents its own rules and reliability becomes luck.

Platform engineering focuses on reducing developer cognitive load by packaging cloud-native primitives into opinionated defaults:

The goal isn’t to hide Kubernetes—it’s to make the safe path the easiest path.

Common pitfalls include:

Mitigations that keep momentum: